From Game of Thrones to Westworld, Canadian cinematographer Robert McLachlan’s crisp imagery brings a colorful, low-key depth to your favorite television shows. Growing up with his father’s photography and home videos, McLachlan fell for film early on and made the decision as a young adult to leave behind a career in cycling to pursue cinematography.

After starting his own production company in Vancouver, McLachlan shot documentaries for Greenpeace, commercials, and corporate videos before landing a job on The Beachcombers in 1988. Shooting a few episodes of MacGyver and The X-Files creator Chris Carter’s TV series Millennium during the 90’s, McLachlan now works regularly on major network series for HBO and Showtime.

Touching on the dynamics of episodic filmmaking, the importance of fine art in cinematography, and an insider’s look at what makes Game of Thrones so successful, Format caught up with McLachlan to find out how he got to where he is now.

Format: You work on all these top-notch series, some of which have quite different aesthetics. Westworld, for example, is shot on film and uses mostly practical effects, while Game of Thrones is shot on the Alexa and uses a fair amount of CG. How did this influence your approach working on each show?

Robert McLachlan: First of all, the major difference between digital and film now is that digital is so much more light sensitive than film. Doing Westworld, after five years of not shooting film, required much heavier lighting requirements than I’d been working with. The viewer’s sophistication and eye have been so spoiled with CG-enhanced images and cameras that can dig deeper into the shadows, so we had to light Westworld in a way that didn’t look goofy.

For instance, and this is no criticism of them, in Dances with Wolves when Kevin Costner is in the prairie, they lit as much as they could, but at a certain point it just fell off to dark and looked a bit fake and theatrical. We had to shoot similar things on Westworld, but instead of defaulting to the way they used to do things we used massive amounts of light to properly bathe the prairie at nighttime.

Filming on the set of Westworld via Art Spirit Village

I’m not sure there’s a huge advantage to shooting on film, other than it looks beautiful and is very forgiving. Especially when you can’t afford to do a full 4K or 6K transfer, which film is perfectly capable of doing, it’s just wildly expensive. When you’re taking that 6K-capable film and doing 2K transfers, I’m not sure what the advantage is.

However, the showrunner on Westworld, Jonathan Nolan—and, from what I’ve read, his brother Christopher Nolan—would argue that there are philosophical benefits to shooting on film. A lot of episodic directors have gotten lazy because digital is so cheap. They’ll just keep the camera rolling, tell everybody to go back to first position, and repeat without cutting to save a minute or two. It’s not great for the filmmaking, even with the most disciplined and professional actors and crew. With film, everyone knows that each second film is rolling is very expensive. That really snaps everyone into bringing their A-game. I think that has a subtle effect on the finished product, but film definitely has its drawbacks.

In television, directors are sometimes talked about as craftspeople (i.e. their job is to maintain the tone of a show) versus film directors who are often thought of as the authors of their film’s tone. Does your role as a cinematographer fit into this dichotomy?

In episodic work, I wouldn’t even say directors are craftspeople. The producers, who are also the head writers, are very much in control of their show. When you start an episode, whether it’s a procedural drama for CBS or Ray Donovan, it will be made very clear to new directors what the theme’s intention is and what the producer expects. If the DP is shooting every episode, he’s prepping the show in that way too. Regardless, it’s the cinematographer’s job more than anyone’s to keep a visual consistency.

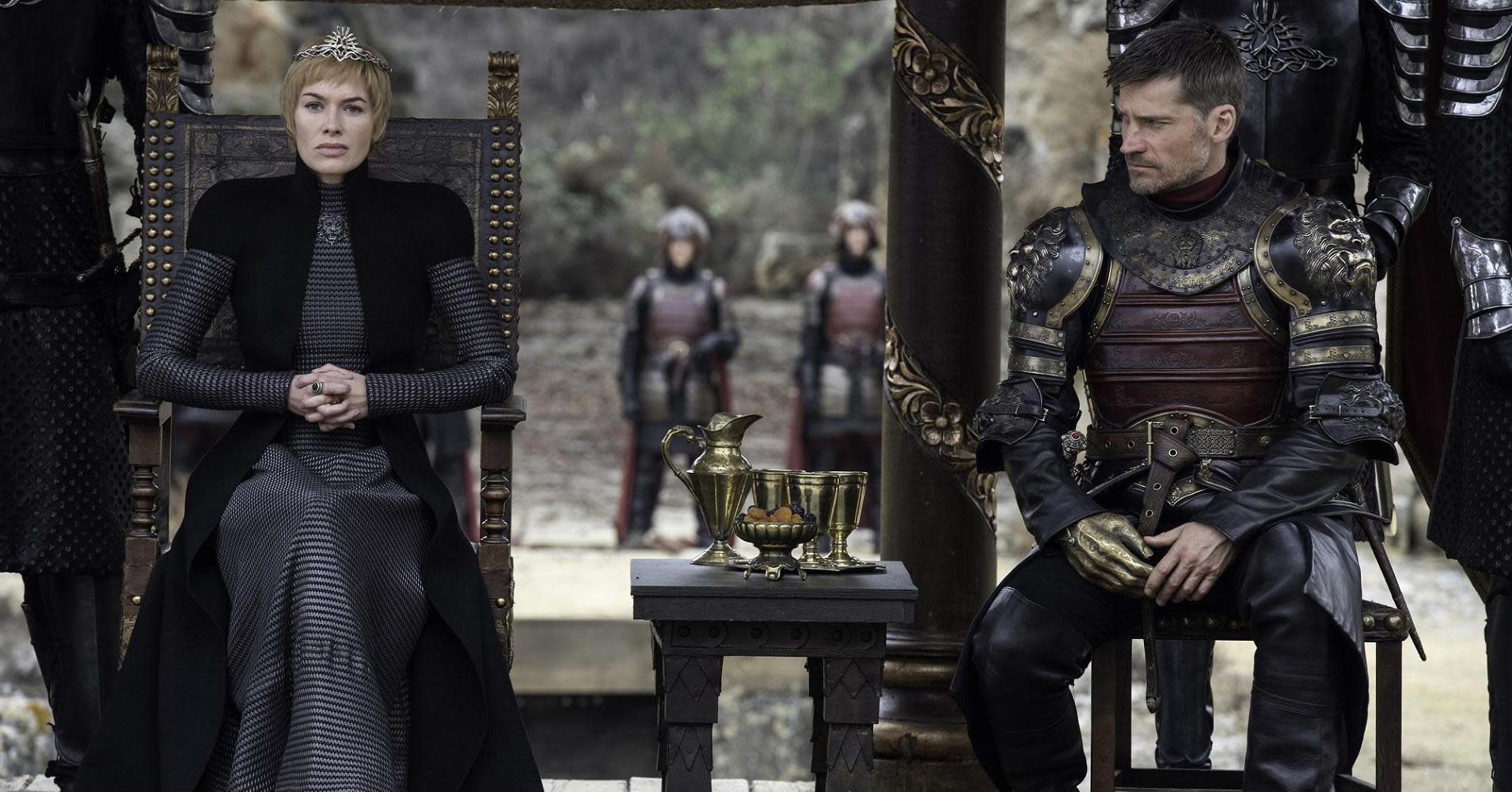

On Game of Thrones normally there are about five DPs. We all get iPads at the beginning of the season with frame graphs organized by set and location for the last several seasons so we can see how each set has been handled and what kind of contrast and filtration were used. There’s always room for interpretation, but we’re familiar with the show and those stills are a really good visual shorthand.

Game of Thrones still courtesy of HBO

How do you use the creative leeway you do have?

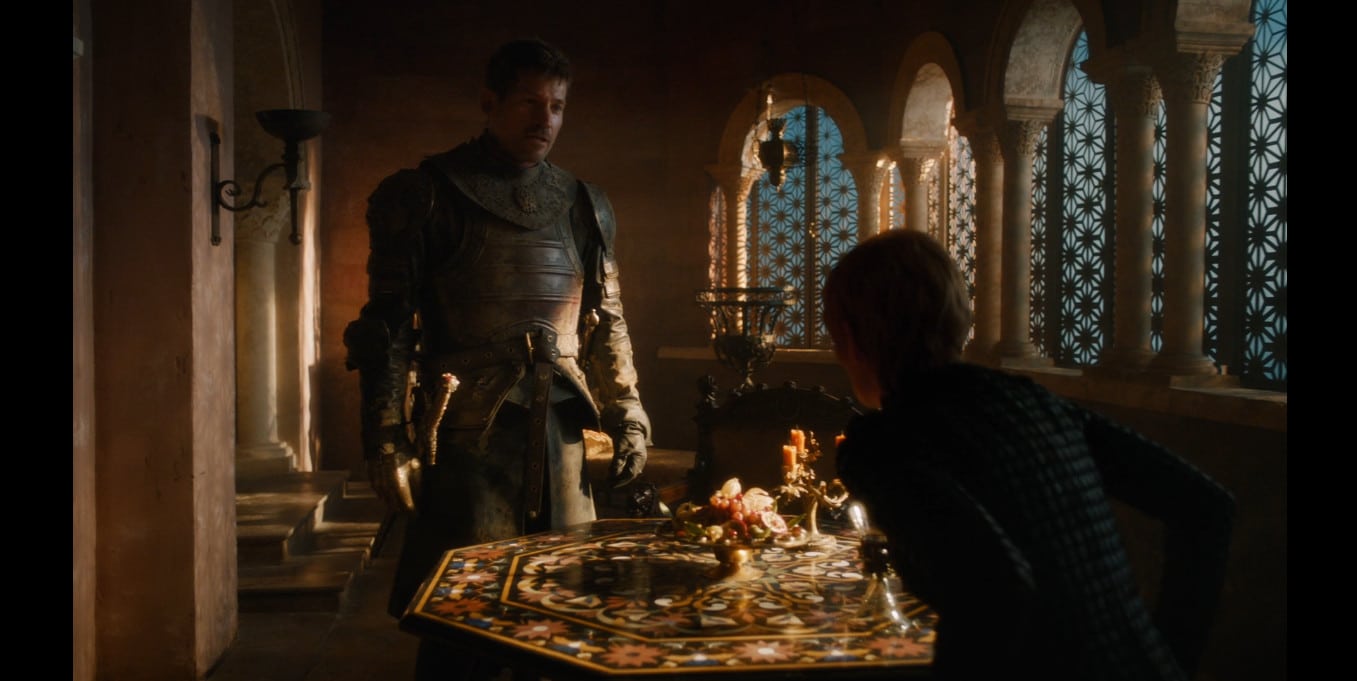

In one of the most recent episodes, “Eastwatch,” I was the last to shoot a scene in Cersei’s chamber. There was a closed-in balcony behind a lattice, and the only backing behind that was a huge sheet of sky blue, which had no character whatsoever. The last time I shot the chamber I just blew the lattice out so it felt like a hot, white sky outside. This time I wanted to add more texture. Jaime delivering this information about the changing nature of war to Cersei seemed like the equivalent of witnessing the A-bomb drop in the form of a dragon. I wanted it to feel like the sun was setting on the Lannister Empire, and that fit with time-of-day in the storyline. I put a 5,000 watt light—which isn’t that big of a light by our standards—right in the shot just outside the lattice. I helped it out with a couple of other lights and added enough smoke and atmosphere to disguise the stand that I didn’t have time to hide. You’ve always got leeway, and fortunately creativity is rewarded on Game of Thrones.

Going back to the beginning of your career, why did you decide to leave a successful career as a cyclist to pursue filmmaking?

Let’s just call it a promising career. You couldn’t really make a living as a cyclist in Vancouver during those years. At that age, there’s a lot of pressure to decide what you want to do, where you want to go to school, what you want to study. My dad was a bit of a bohemian, an illustrator, painter, avid home movie-maker, and photographer, so I had access to all that stuff at an early age. I liked making little movies, I liked photography, I liked going into the darkroom, and I loved going to the movies. When I asked myself the question, ‘What do I love and how am I going to make a living doing it?’ choosing was the easy part. The hard part was sticking with it through some really tough, slim years. I was at least thirty years old before I started to reap any real comfort or financial rewards from the work. But I was able to keep doing it under less-than-ideal circumstances because I really loved it.

Those are comforting words! When you started out as a DP, did you have a specific vision of where you wanted to arrive later in your career?

Buried deep in the back of my head was a goal that I certainly couldn’t voice out loud for fear of ridicule and could barely admit to myself for fear of self-ridicule, which was doing exactly what I’m doing now: shooting big movies and productions like Game of Thrones. Of course, when there’s absolutely no evidence of any possibility of that ever happening, and you find yourself shooting commercials for local pizza joints just to practice lighting and shooting, a goal like that is pretty hard to admit. One thing I learned from cycling was that if you work hard enough, keep your focus sharp enough, and have a clearly defined goal, it’s probably going to be attainable. I take that back, it is going to be attainable.

Did you have a strategy to get there?

When I started out in Vancouver doing documentaries for Greenpeace, training films, marketing films, one very low-budget feature, and a few little dramas, I was putting in my ten thousand hours.

I formed a production company, Omni Film Productions, with no real business plan other than it was easier to talk someone into letting me make a marketing film and hire myself as a cameraman than it was to get them to hire me as a cameraman. Then American film production discovered the cheap Canadian dollar and Vancouver as a great location, and there was this explosion of film work. After doing one iconic little series called The Beachcombers, I was hired for the second unit, and eventually the first unit, on one of the biggest shows on TV at the time, MacGyver. American productions were looking for local DPs so they didn’t have to relocate Americans to Canada and pay all these additional fees, and here was this local kid who had the experience.

Because I put my time in when I got my chance, I not only didn’t blow it, but I did quite well at it. By the end of the first union show that I was a camera operator on, I was the show’s DP. I think I was thirty-one-years-old.

While it seems like there are fewer technology barriers to becoming a cinematographer nowadays, many argue that you still need access to top-of-the-line equipment to make an excellent product. What do you think?

Today’s huge advantage is that it doesn’t cost you a fortune to shoot. In my day, I had a 16mm camera. A roll of film would transfer about ten minutes, and by the time you’d purchased and processed it, you were looking at about $100. That was a lot of money. So you really needed someone else to bankroll you, even if it was the local chain of pizza stores. Nowadays, the media that you’re recording doesn’t cost a thing, and you don’t need an Alexa or a Red to practice your craft.

My advice to kids who want to be cinematographers is, first of all, from what I can tell, most of the film schools suck. The programs aren’t taught by people who have been out in the trenches and done it. I know there are exceptions, and I apologize to them, but for my money, there’s no substitute for going out and shooting if you want to be a cinematographer.

Even practicing color correcting stills in Lightroom or Photoshop can be really helpful. You can get the entire technical side of things under your belt without fancy equipment. That’s major, because you can’t be thinking about that stuff when you’re suddenly dealing with a camera department of 25 people. If you have some conflict resolution skills and patience, that’s really useful too.

Nowadays, Hollywood camera operators’s points of reference are all from film and television. But in terms of composition, if you want to be a cinematographer it all starts with fine art. Guys like Gordon Willis knew there’s nothing new under the sun, but if you soak up the fine art masters’s work you’re going to produce much better images than if your references are Star Wars and Gilligan’s Island.

A couple months back, I was doing a talk about the photography of Ray Donovan at the ASC clubhouse. I had a room full of cinematographers and students, and using fine art as a reference was a completely new concept for them. Some had never heard of history’s most famous painters. I love working with European camera operators because they’ve all grown up being dragged through the National Gallery, the D’Orsay, or the Louvre. On one Game of Thrones sequence in a meadow with a broken-down cart, I said to the camera operator, ‘Dave, I want this establishing shot to be a John Constable.’ I could say that to any camera operator in Hollywood—probably in Vancouver or Toronto too—and they wouldn’t have a clue what I was talking about. But Dave said, ‘Ah yes, “The Hay Wain”,’ and he framed it up exactly the way the painting is.

John Constable, “The Hay Wain”, 1821. Oil on canvas

J. M. W. Turner, “The Fighting Temeraire”, 1839. Oil on canvas

Is there a particular painting you’ve used most closely as a reference for a particular scene?

For the sunset scene in “Eastwatch” where I stuck the light right in the shot, we used some famous J.M.W. Turner paintings, like ‘The Fighting Temeraire.’ I also looked at some genre paintings by David Teniers and Adriaen Brouwer. Their works depict these gloomy interiors with just a little window light coming in. They’re not afraid of the dark. The great artists going back to Da Vinci, never mind Rembrandt, weren’t afraid of silhouette. That’s really helpful for understanding how to use atmosphere to blend light and create more depth in the shot.

Knowing what you know now, at this stage in your career, would you suggest any sophisticated techniques to cinematographers working on small-budget productions for making something amazing without having much of a budget?

In 1992, I did a little film called Impolite with a director named David Hauka. We only had about half a million dollars to make it, but we managed to land Christopher Plummer for a fews days to do a small part. We didn’t have much equipment—Panavision was basically loaning us a body, one zoom, and a couple mags. The script was clever, but what we really had going for us was a lot of time to plan. The film won a CSC award for best theatrical cinematography that year, and that was because we were able to plan in advance what time of day and where we were going to film each scene. We practiced and chose our times to make maximum use of natural light so it came out as beautiful as possible. That way, we were able to get the best visual quality with minimal equipment.

Planning and scouting is easier today because you’ve got apps like Artemis to tell you where the sun will be at a specific time on the day you’ll be filming. On the “Dance of Dragons” episode in Game of Thrones, we had three or four days to shoot so we knew we had to work unbelievably fast. I’m talking over eighty setups on days when the sun comes up at 8:30 a.m. and sets at 5:30 p.m.

That sequence looks fantastic because we planned our days shot by shot according to where the sun was. If you watch it, almost every shot is either backlit or under a canopy, which meant that as fast as you could move the camera over and point it, we were ready to go. That’s something anybody can do.

What was it like shooting “Eastwatch”?

When we got the scripts for season seven, we all kind of liked “Eastwatch” best. Having done so many big action sequences with large CG components on Game of Thrones, I was really looking forward to the simple scenes in “Eastwatch,” like Tyrion and Jaime in the catacombs. We were all inspired by that location, which was a 700-year-old former shipyard of the Spanish Armada in Seville, Spain. It was just a matter of dotting a few lights throughout to give it some depth and mystery. The blocking was very simple between the two actors, the writing was sublime, the acting was outstanding—that makes for a very satisfying day as a cinematographer.

Want to reading more about filmmaking?

Award-Winning Cinematographers Explain Cinematography

‘The Walking Dead’ Director Michael Satrazemis Shoots Zombies With Film

Saturday Night Live’s Colorist Josh Bohoskey Gives Feeling To Film*

*Additional reporting by Benjamin Tersigni/Header image via [HBOWatch](http://hbowatch.com/where-was-game-of-thrones-filmed/)*