Art is all around us, from graffiti to a child’s drawing on the fridge. Human artistic history goes back more than 300,000 years to when people painted in caves, made decorative jewelry, and created human-like figurines. Art spans nations, ethnicities, and cultures. But how did art become so universal? Is art rooted in culture, learned and passed down from generation to generation? Or is art rooted in genetic adaptation, providing us with an evolutionary advantage over our competitors? Evolutionary psychologist Anjan Chatterjee explores these explanations in his book The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art.

The art-as-culture theory categorizes art as a skill or “technology” that must be learned. This theory sees art as comparable to reading and writing—skills that are undeniably useful but not genetically heritable. Another example of a cultural technology is language. Though we all have the capacity for language, we are not born with the ability to communicate through the spoken word. We must learn the tongue of our guardians, and the words, grammar, structure, and tone often differ widely across cultures. Similarly, the form, design, and function of art vary extensively across cultures.

Artists and scientists alike have been attracted to the art-as-adaptation theory for the origin of art as a way of validating art’s existence. Of course, art does not require a biological basis for us to recognize its value, but many art lovers see support for the genetic foundation of art as ammunition against the philistine notion of art as superfluous.

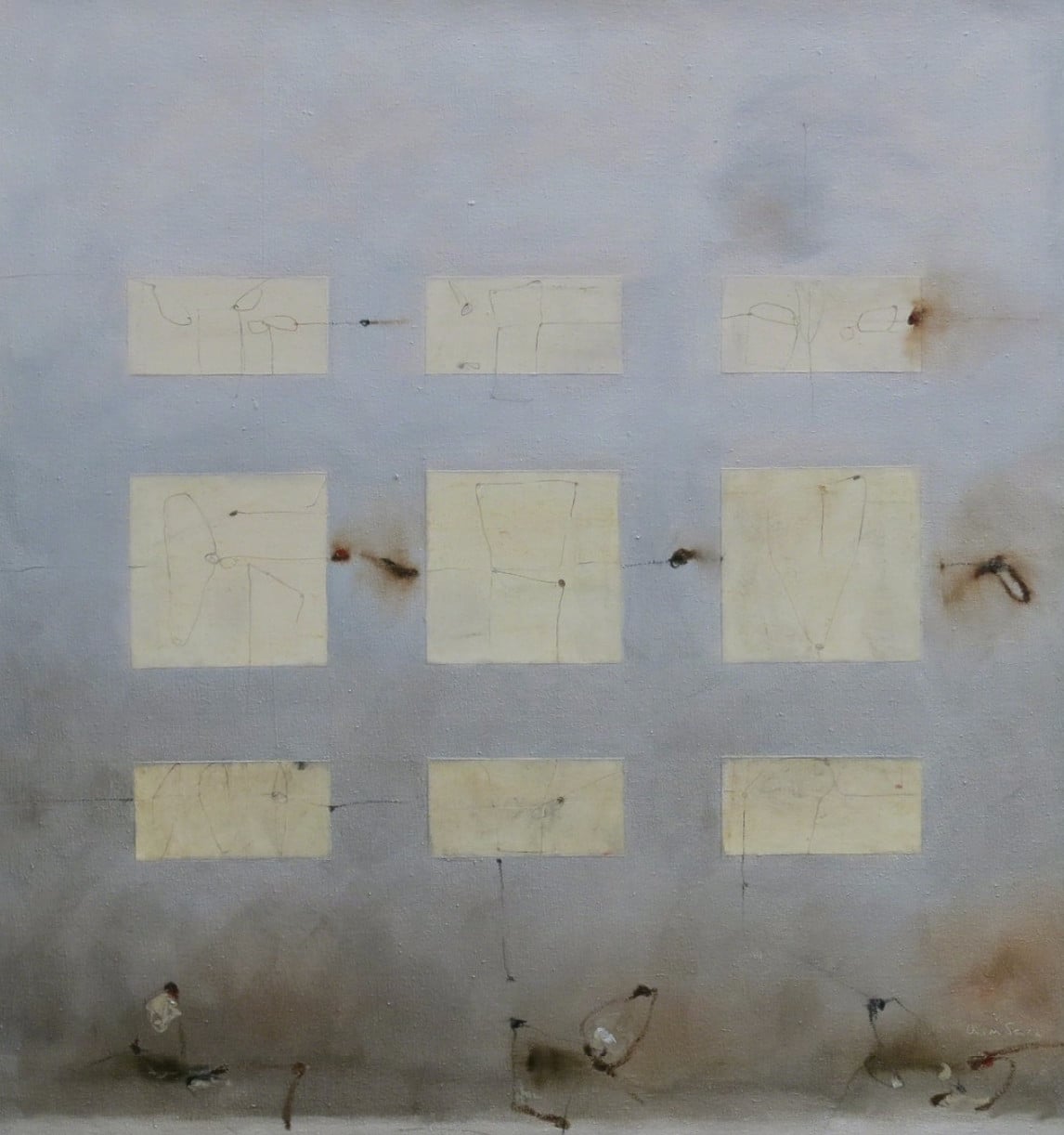

Ana Maria Sanz, Community of Two, Mixed media on canvas

Is art about community and social behavior?

One adaptive explanation for the origin of art is that artistic behaviors evolved to bring communities together. It is well known that individuals who are involved in their communities have greater health, wellness, and, therefore, better chances of survival. Scholar Ellen Dissanayake argues that art is a manifestation of the human impulse to “make special.”

Her theory puts forth that humans have an innate desire to elaborate otherwise usual objects and behaviors. This elaboration of behaviors, or “ritualization,” binds people together under a common set of beliefs and values that are paramount to group cohesiveness. These specialized relics, costumes, dances, and songs gave rise to what we now call “art.”

This is a seductive idea, but art is not always about bringing people together. In fact, much of art is enjoyed in solitude. For example, many music-lovers prefer to listen in the privacy of their own homes. By the same token, plenty of visual art aficionados choose to view paintings and drawings in the quiet of a secluded gallery.

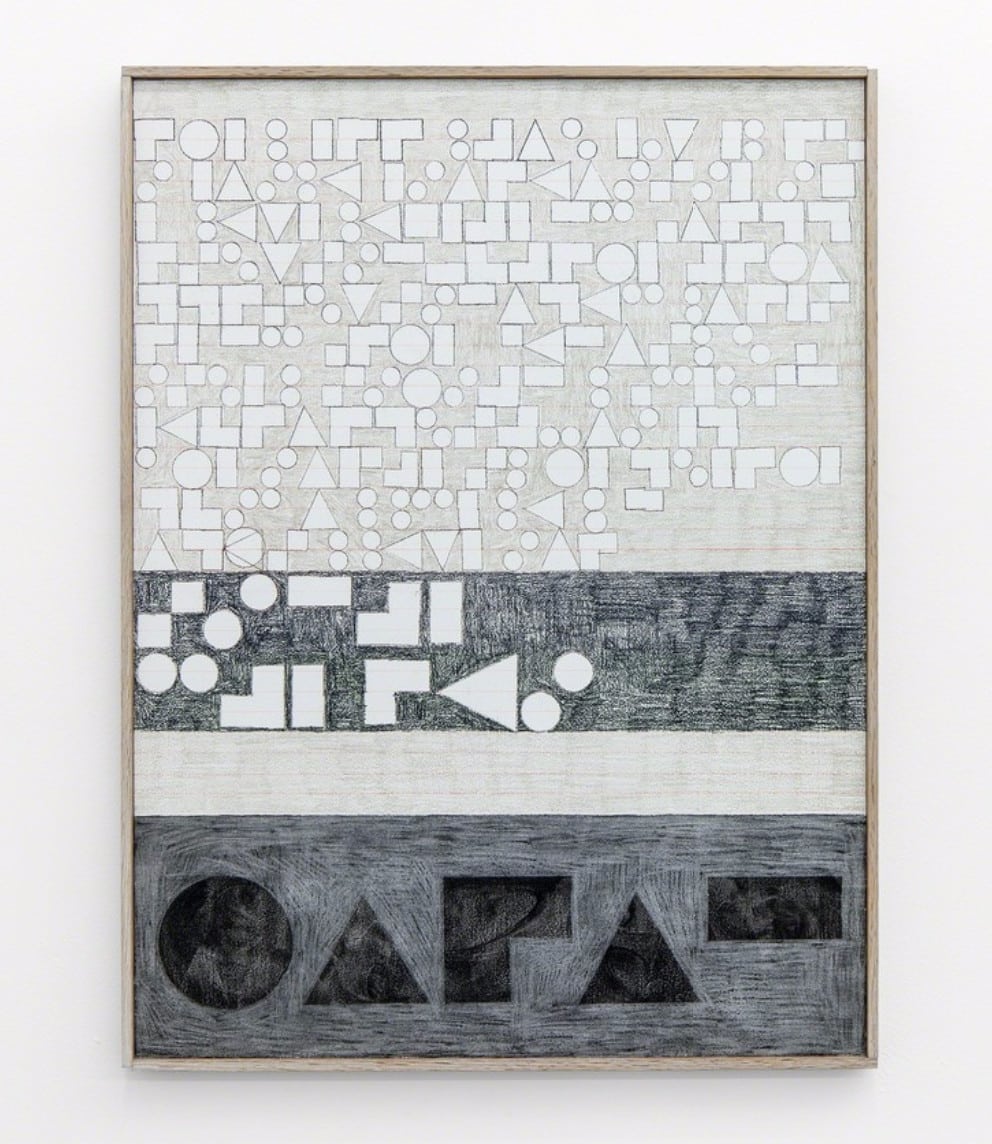

Derek Sullivan, Storytelling, Coloured pencil on gessoed wood panel

Or is it about communication tool for survival?

Artistic behaviors could also have evolved as a way to relate information that aids in our survival. It does not require a stretch of the imagination to see how storytelling could have been used to pass down valuable knowledge that helped people stay alive. Think of stories told around the bonfire about “the man who escaped the bear” or “the woman who found a leaf to cure stomach sickness.” These ideas could also be communicated through song, dance, drawings and paintings. The issue with this explanation is that, like community building, not all art is a conduit for information.

Laure Prouvost, Sexy Shovel

Could it just be about sex?

A third biological explanation for the origin of art is sexual selection. The idea of sexual selection is that our artistic behaviors evolved, not because they help us to survive, but because artistic individuals make the most attractive mates.

A common example from nature of sexual selection is the peacock’s tail. The elaborate feathers displayed by male peacocks make them more obvious to predators, decreasing their chances of survival. At the same time, extravagant plumage advertises high quality genes to females, increasing the males’ chances of reproductive success.

Cognitive psychologist George Miller compares our artistic inclinations to the peacock’s tail, proposing that art evolved to showcase intelligence, insight, dexterity, and other traits desired in a mate.

The primary issue with this theory is that sexual selection acts primarily on men, and men are not the only art-makers. Both women and men are recognized as acclaimed artists today and throughout history. Furthermore, in early tribal societies, women often were the primary creators of textiles, clothing, pottery, and other art forms.

Heidi Schwegler, Something’s Wrong 01, Cast glass

Maybe we’re asking the wrong question.

If art is not a genetic adaptation, then art must be learned and passed down through culture, right? Perhaps, but some academics have argued that we shouldn’t even ask the question, “Where does art come from?” and that “the arts” may be an invention of Western philosophers.

It is true that for centuries, “the arts” were encompassed into the study of mathematics, astronomy, rhetoric, and science and were not recognized as distinct areas of expertise. Definitions for art continue to transform and often differ drastically from culture to culture and even person to person. Some modern art includes elements from pop culture, factory-made objects, or even objects that many people would not consider art. So, if we cannot agree on a universal definition for art, how can we discuss its origins?

Though we may differ in our understanding of certain art forms, there is no question that art is part of every community across the globe. People have been creating music, dancing, painting, drawing, telling stories, and bringing all these art forms together in ever-changing ways for umpteen generations. Anjan Chatterjee argues in The Aesthetic Brain that it does not make sense to see art as purely genetic or cultural. He uses the brilliant metaphor of the Bengalese finch’s song to illustrate a more nuanced explanation for the origin of art.

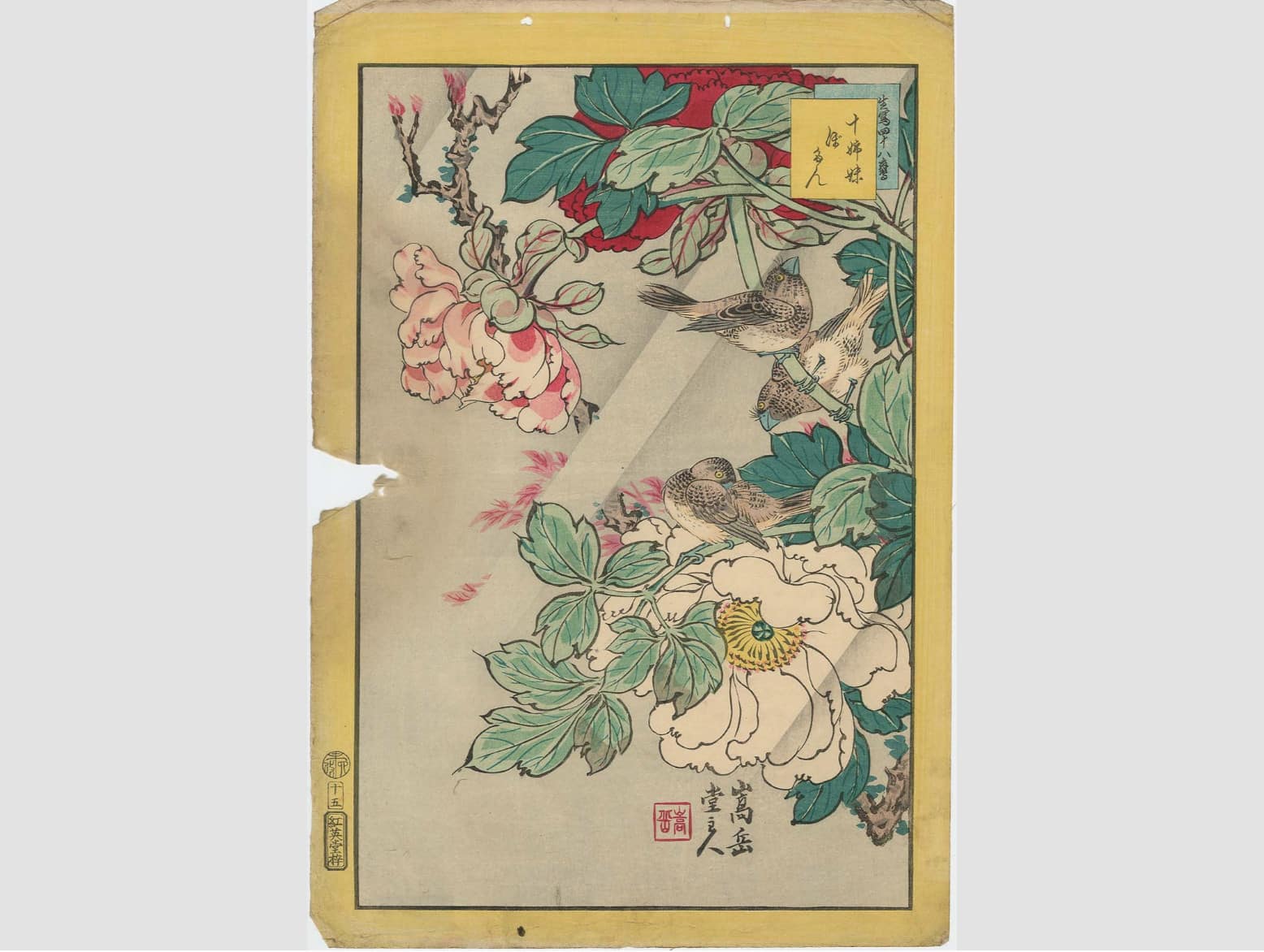

Nakayama Sûgakudô , Bengalese Finch and Peonies, Woodblock print

Consider the Bengalese finch.

The Bengalese finch is a Japanese bird bred from the wild white-rumped munia. Male munias sing a very specific song to attract female mates. Hundreds of years ago, the people of Japan began capturing wild munias and breeding them for their colorful plumage. Over the course of 250 years, the wild munia evolved into the domesticated Bengalese finch.

Interestingly, while the birds were being selected for their colorful feathers, the quality of their singing did not suffer. Instead, the finches’ songs became even more impressive. When singing ability became irrelevant to reproductive success, the birds were freed up to sing more diverse and varied tunes. A wild munia can only learn the stereotyped song passed down from his ancestors. By comparison, the Bengalese finch can learn new, beautifully complex songs that incorporate elements from their social environment.

According to Chatterjee, art is like the Bengalese finch’s song. While there is little question of art’s adaptive roots, art no longer holds an adaptive purpose. Like the Bengalese finch’s singing ability, the selective pressures on our artistic abilities have relaxed, enabling us to diversify our artistic behaviors for nearly infinite purposes.

Art can bring communities together, communicate information, or impress potential mates. Art can also be an expression of beauty or a rebellion against entrenched ideas. Art can present a new perspective or celebrate an ancient tradition. Art can be a political statement or a meditation on spirituality. We don’t have to look further than our own species’ kaleidoscopic history of creativity to see there is no end to the reasons for which we create and enjoy art.

Header image: Maurizio Cattelan, View of the exhibition KAPUTT, 2013 Taxidermied horses/All images via Artsy