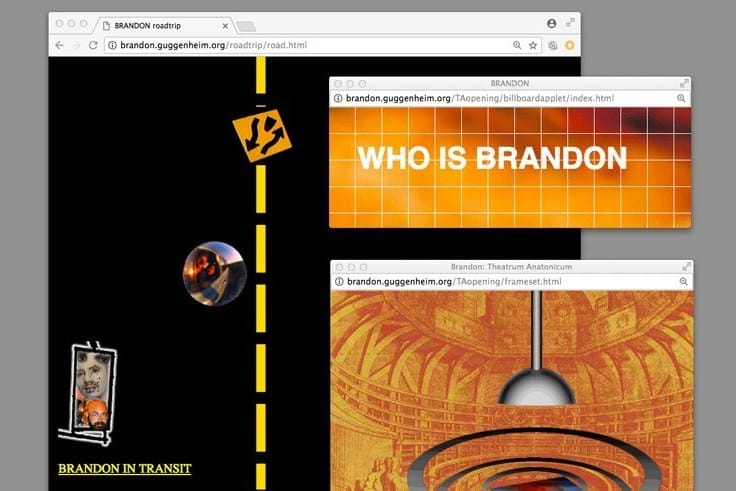

The infrastructure of the internet has changed so rapidly since its inception that huge swaths of the web have been lost—among these many of the groundbreaking works created by digital artists in the internet’s earliest years. Until recently, this was the case for Shu Lea Cheang’s Brandon. The first online work to enter the Guggenheim’s collection in 1999, it has just been painstakingly restored by a team of digitally-minded conservators.

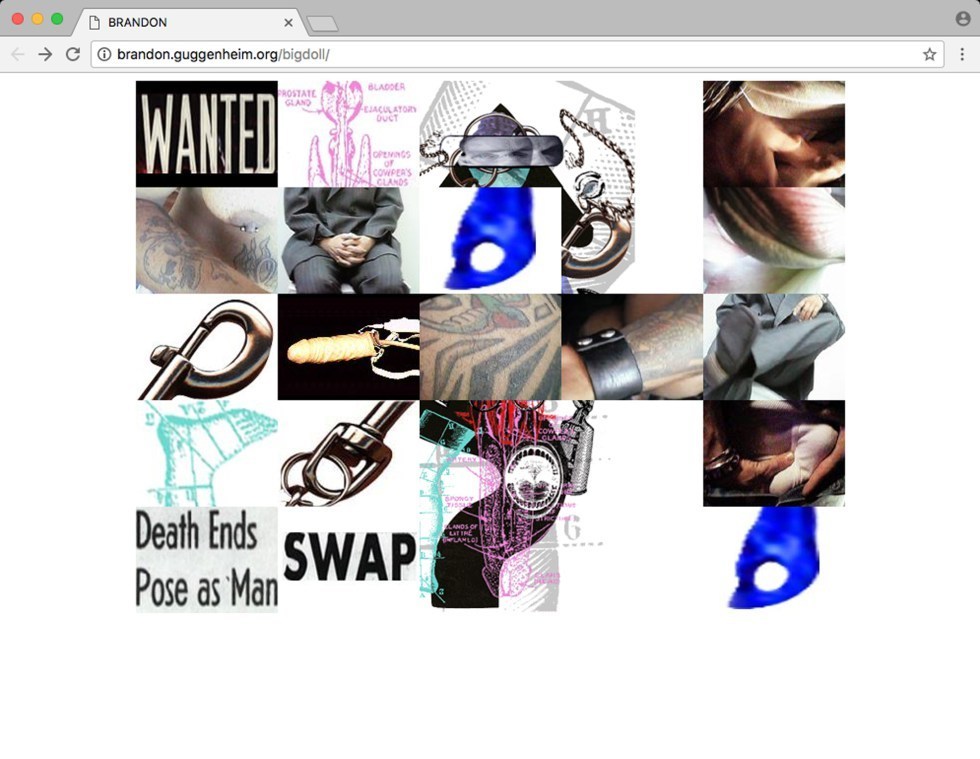

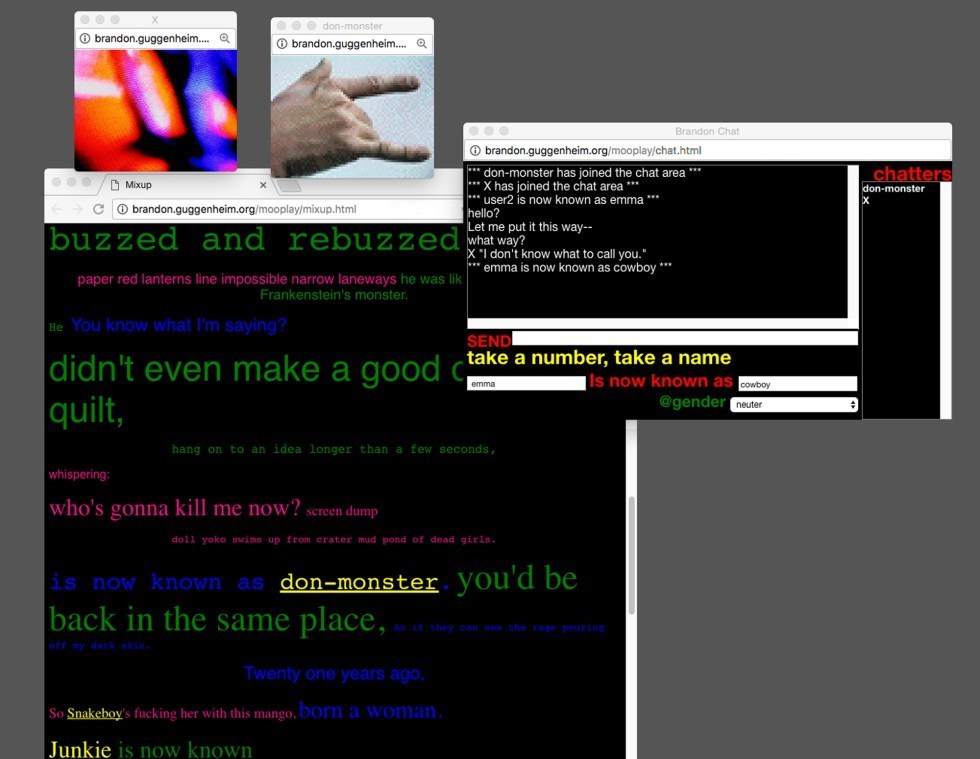

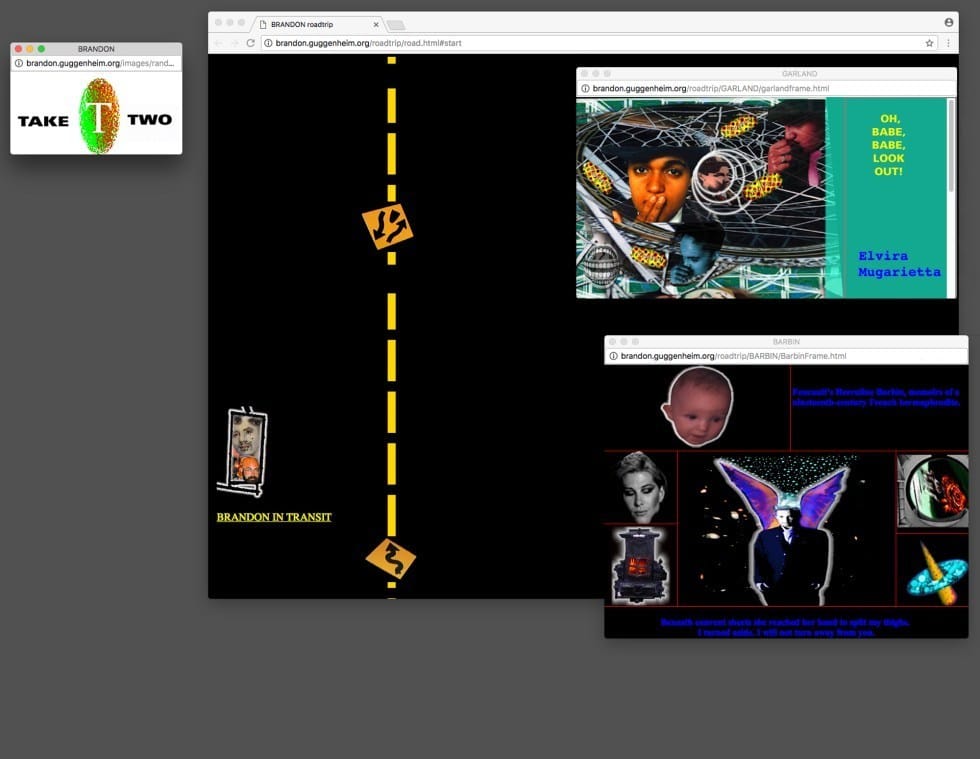

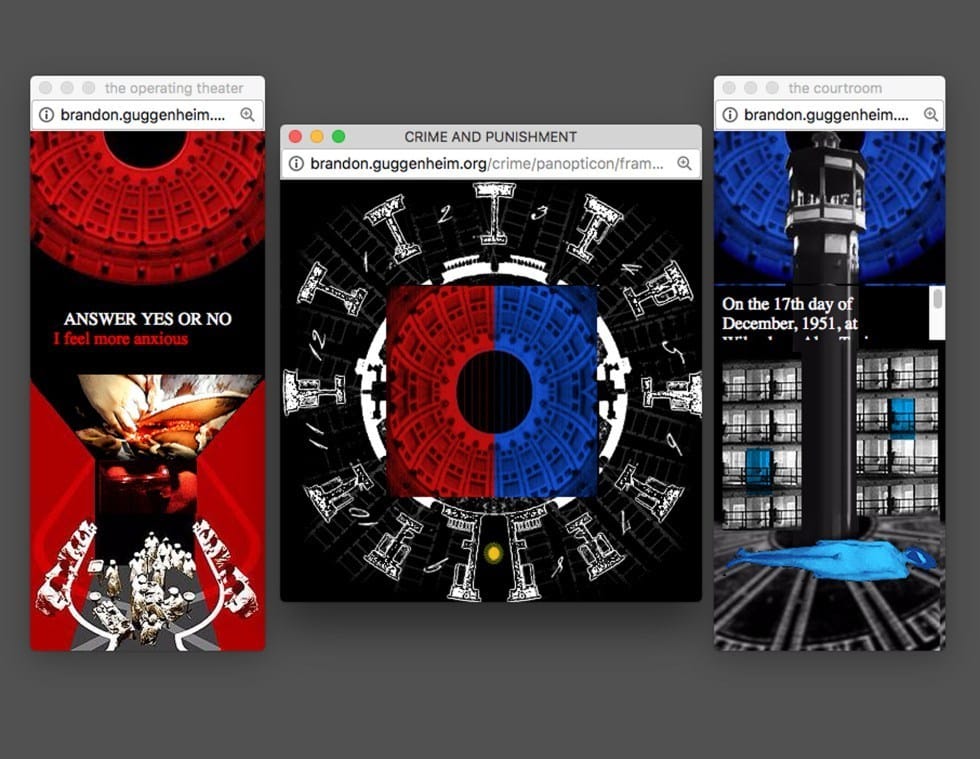

Brandon explores the tragic story of Brandon Teena, a trans man who was raped and murdered in a Nebraska hate crime in 1993. “A prime example of ‘cyberfeminism,’ Brandon utilizes technology as a means to break down social assumptions about gender in both the realm of technology and in society at large,” the Guggenheim explains. For one year, between 1998 and 1999, collaborating artists and programmers uploaded work to the website, and viewers engaged in live chats and webcasts.

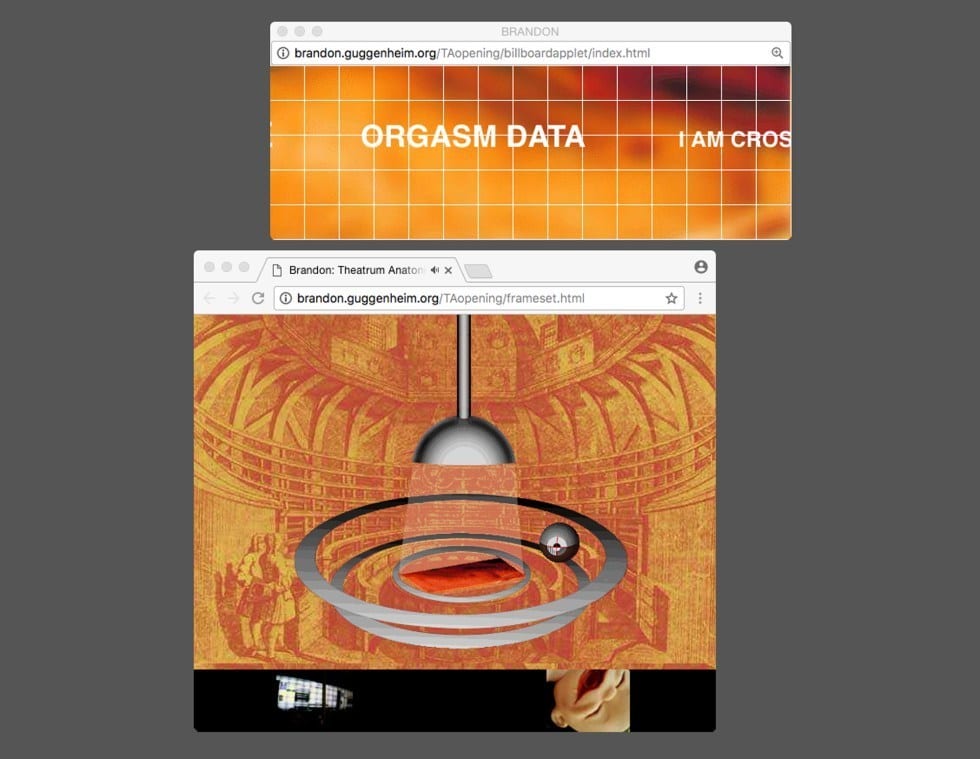

Brandon remained online after this time, but began to slowly disintegrate, like a painting faded by too much sunlight. Contemporary web browsers could no longer recognize much of the early HTML code used on the site, or support the unique Java applets used to animate its text and images. In December 2016, Conserving Computer-Based Art (CCBA), a joint initiative of the Guggenheim and NYU, obtained approval from Cheang to restore the work.

GIF via Rhizome.

It wasn’t an easy task. Brandon is made up of a total of 82 pages. Furthermore, as the CCBA team notes in a blog post, “The artwork’s technical composition proved to be exceptionally complex: the original website contains approximately 65,000 lines of code and over 4,500 files, which include a hidden archive of research materials.” In keeping with standards of art conservation, none of the artwork’s original code was deleted, and every change was carefully annotated.

Now fully restored, Brandon is again publicly accessible at http://brandon.guggenheim.org. It has recently been included in Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology. The multi-layered spaces of the work retain an immersive and unsettling feel. “Brandon was conceived at a time that I moved from actual space to cyber/virtual,” Cheang said in a 2012 interview with Rhizome. The artist also noted the deliberately unclear layout of the site, suggesting that “Brandon is like a puzzle,” which the disoriented viewer must attempt to navigate.

Brandon therefore asks the viewer to question their own embodiment in a multitude of ways: how do we exist in online spaces, and in gendered spaces, and how are these worlds related? As our online experiences expand, such questions only become more pressing. And although the landscape of the internet has changed vastly since Brandon was created, political progress has not been as rapid. The continued timeliness of Brandon’s story is a reminder of how much we still need artworks like these to bring trans rights into public focus.

Screenshots via the Guggenheim and Jonathan Farbowitz.