Social media has been around for a few presidential election cycles, but even though this year’s Republican nominee tweets at all hours, it doesn’t mean you can post whatever you want on Election Day.

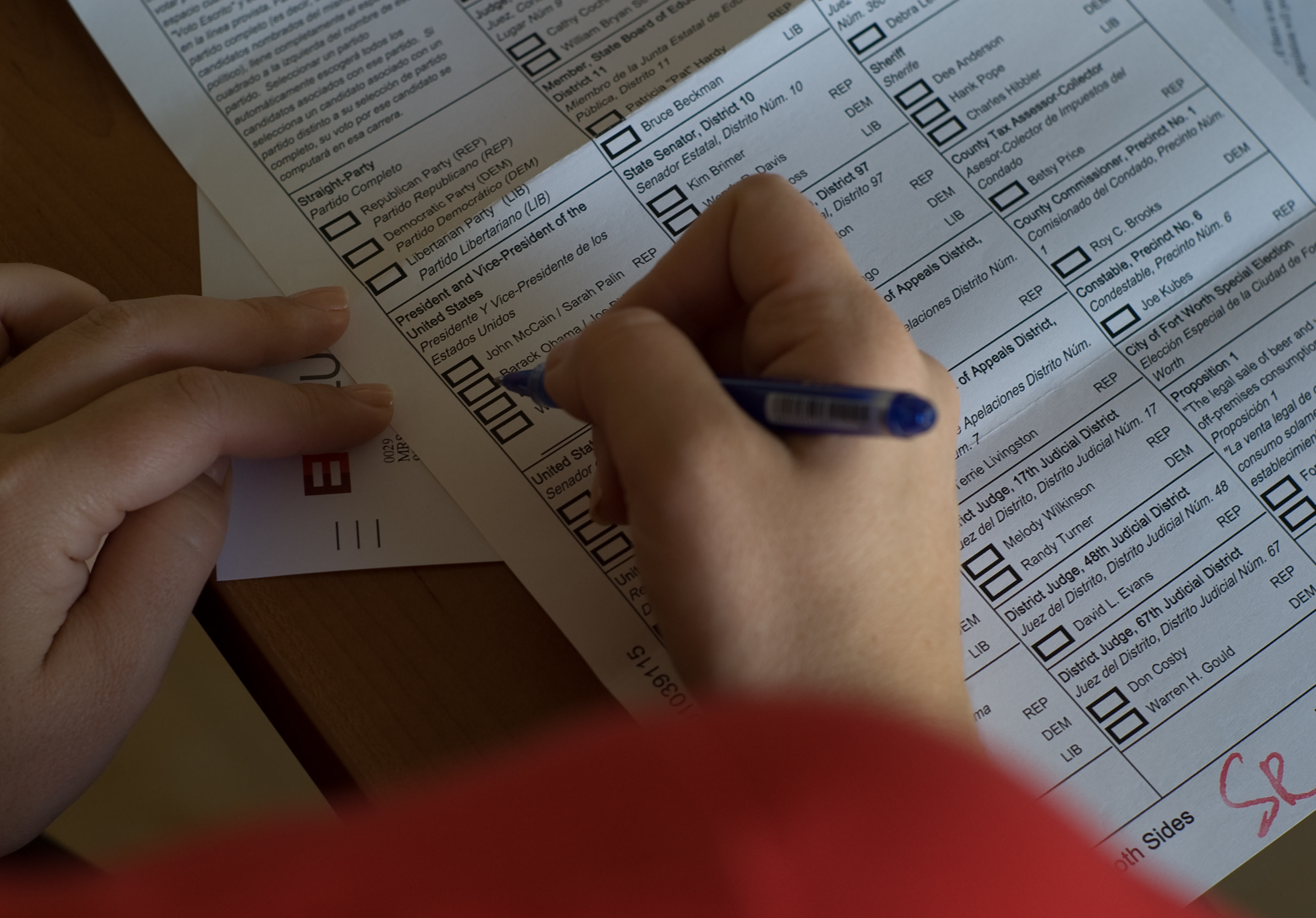

In case you didn’t know, taking a photo of your marked ballot (which has become known as a “ballot selfie”) is illegal in 25 American states that restrict photography in the polling place. As of September 2016, there is no federal ban, and these restrictions are made on a state-by-state basis.

If you’re voting in Arizona, Delaware, Indiana, Maine, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah or Wyoming, you can snap away—these are the only states that clearly allow (or at least don’t clearly forbid) ballot selfies.

But what’s the issue with the other 25 states?

Until recently, there was a New Hampshire law that prohibited voter’s ballots from being “seen by any person with the intention of letting it be known how he or she is about to vote.”

Representatives who voted in favor of the bill believed that if ballots were allowed to be photographed, voters could be coerced to vote a certain way by an employer, spouse or union rep—and the ballot photo posted on social media would serve as proof.

The law was passed in 2014 and overturned by a federal court in late September 2016. Under the short-lived ban, voters faced a misdemeanor and up to $1,000 in penalties for posting a ballot selfie.

One of the plaintiffs from the case, Andrew Langlois, was investigated by the Attorney General’s office after posing a photo of his ballot on Facebook (he had written in the name of his dead dog, Akira, as his choice for senator in the 2014 Republican primary). Langlois was astounded that he was being investigated for posting his ballot photos, according to the civil complaint (the other two plaintiffs, however, were elected officials and posted their ballot selfies in protest of the law).

Snapchat jumped in and filed an amicus (“friend of the court”) brief against the law. The company wrote that their news team has received thousands of photos and videos from inside voting booths, and that “some of these Snaps are relevant and important parts of the organization’s political news coverage.”

Is it true? Do ballot selfies coerce votes?

Ruling last month, the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston found that “digital photography, the Internet, and social media are not unknown quantities—they have been ubiquitous for several election cycles, without being shown to have the effect of furthering vote buying or voter intimidation.”

Brian L. Frye, an associate professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, said one of the problems in the case was that New Hampshire Secretary of State William Gardner wasn’t able to show that social media and ballot selfies actually led to voter fraud.

“He simply asserted that vote fraud is a problem, without presenting any meaningful evidence that that is the case. The law is a solution in search of a problem, which burdens voters’ First Amendment rights for no good reason,” Frye told Format Magazine. “People are perfectly entitled to announce their vote publicly or privately.”

Frye said that he doubts the Supreme Court will take up the issue of ballot selfies unless another circuit court upholds the selfie ban (California recently legalized ballot selfies), and that New Hampshire’s selfie ban is a “case of state legislatures passing laws that reflect their unfamiliarity of how new technologies work and how people use them.”

According to Frye, voters probably shouldn’t worry about snapping and posting on Election Day, since elected officials will be unlikely to pursue these “claims that are calculated to make them look foolish.”

Further to the point, Frye asserted that vote buying as a scheme only works in small jurisdictions.

“If a vote buyer tried to verify purchased votes via social media, anyone paying attention would notice a massively implausible spike in ballot selfies from only that small jurisdiction, all going that way,” Frye said. “You might as well make a status update that you are committing voter fraud.

Should you still keep your camera away from your ballot?

Even though Frye thinks you’re in the clear to photograph your ballot, Rod Sullivan, a lawyer in Jacksonville, Florida, who previously taught constitutional law at Florida Coastal School of Law, said that he can see ballot selfies becoming a big problem if allowed across the U.S.

The problem with voter fraud, Sullivan said, is that it is hard to detect. Voter coercion can be as innocuous as receiving a free BBQ meal by showing an “I Voted Sticker.” Sullivan explained that a restaurateur in the Jacksonville area, whose daughter was running for public office, offered that deal in a recent election.

Vote swaying could be less crude, such as an employer saying they’d like to see proof that an employee actually took time off to vote by requiring a photo of their completed ballot as proof.

“Federal judges live in an insulated world, and they think voter fraud doesn’t occur because they don’t get their hands dirty,” Sullivan said. “Those who commit voter fraud are smart and not obvious.”

For voters concerned with the legality of their ballot selfie, Sullivan suggested taking a photo of a marked sample ballot as a way to safely share your political preference.

Image via Wikipedia Commons/Header Image by Steven Depolo