As an artist, your passion drives your practice, in making any work intuition often comes first and the logical brain can take the backseat. As most artists know, this is the exciting part, an adventure down an unknown road.

As an artist you are also your own administrator, navigating the familiar path of gallery submissions, residency applications, and grant proposals. The logical brain takes the wheel on this commute.

Being awarded a grant or residency can provide the support or space needed to produce a body of work. Proposal writing is a necessary, if daunting, part of the process. Artists are so comfortable using their work as a means of communication that shifting into the administrative gear can be challenging.

The following guide outlines some simple steps that will help you craft a proposal that stands out and secures the funding necessary to make your project a reality.

Step 1: The Outline

Projects are not always logical progressions, artists often act on instinct, but once you have found yourself with a body of work or idea taking shape you can best put it into words by asking yourself these key questions:

- What: The project concept, the medium, and the materials

- When: What is your timeframe for completion of the work? If this is a residency, make sure it’s the right time and you’re not rushing

- How: This will be your description of the approach you’ll take.

- Why: What is the significance of the project? If this is for a public art piece here you’ll consider the community, history and site. If it’s a residency: are you connecting to something specific about the place, or the programming that is also tied to the proposed work? Essentially, you’re asking yourself why others are going to be interested in this work, and why the deciding body should support you in your application.

- How Much: Finally, some calls for proposals may ask for a specific project budget. Depending on your practice, this might be the time to sit down with a list of materials and narrow your focus. If your project is less dependent on physical materials, it’s good to start with a general idea–this can broaden the opportunities for support.

Before you get to the point of submitting an art proposal, be sure these are questions you have answers to. If not, consider giving yourself more time for the project to take shape.

Step 2: Do the Research

Make sure you’re subscribed to newsletters from granting bodies, residency aggregators, art galleries, and calls for acquisitions from city, state, or provincial art councils.

You don’t want to hear of the opportunity right before the deadline–or worse, after it has passed. Start writing your general proposal two months in advance. You’ll need time to build the foundations of your package, and additional time to edit it specifically for the submission(s) at hand.

Being thorough in your research and getting an early start will leave time to thoroughly check all the boxes called for in any submission, which can vary significantly!

Step 3: Meet the Brief

A lot of effort goes into a proposal–be sure that yours is suitable for the call, and that you’re eligible! Some grants and calls for proposals can be specific to career point, current residence, or medium. You will save yourself time and disappointment if you’re certain you and your work meet the brief.

You can do a deeper dive and look at past grant recipients, residency participants, or exhibiting artists. Determine if what the deciding body says they’re looking for matches their past decisions. There are a lot of opportunities out there, take the time to find the right one for you at this point in your career.

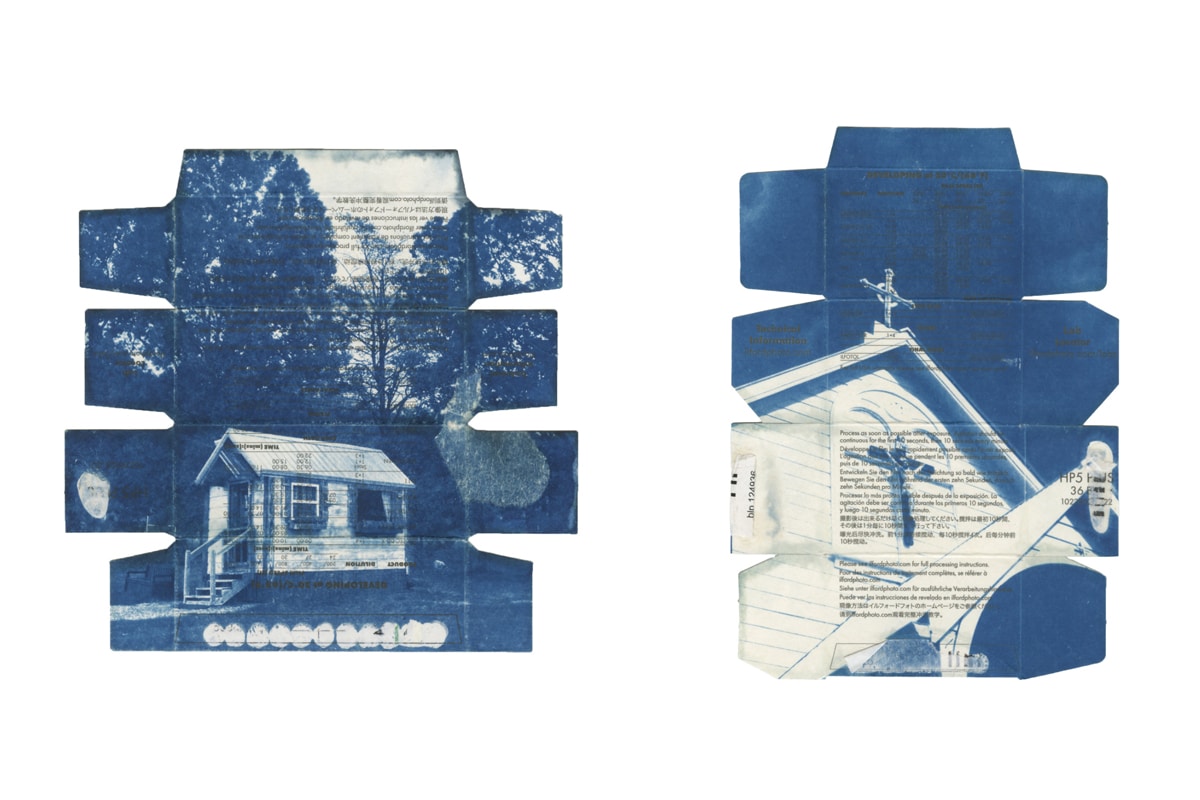

Step 4: Image is Everything

Your supporting media will be the first items a jury, committee or curator will view. Make sure your first impression isn’t your last. Using great images will not only best represent your work, but demonstrate your professionalism, and respect for the individuals reviewing your proposal.

Remember: a bad photo can ruin the impact of an incredible artwork.

Quick tips for getting the best images:

- Hire a professional. Documentation is its own category of photography. Photographers who specialize in art documentation are skilled in lighting, color correction, and focus for all manner of mediums and surfaces. Ask for recommendations from other artists, look for image credits on documentation from your local galleries.

- Be sure your photographer provides you with hi-res TIFF files. If you’re the kind of artist whose work simmers for a long time before suddenly boiling and your work is done just before the deadline, see if they can guarantee quick delivery of edited images.

- Professionals can cost, well, what they’re worth, and that’s exactly the kind of world you’re looking to live in. If you aren’t able to pay the rate, you can typically find a photographer who is willing to trade for a piece of your work of the same value ($300-$700)

- Take your own photos. While hiring a professional is the best option, with some effort and expert documentation tips, it is possible to achieve professional-looking photos. Yes, even with your phone–especially if it can take RAW images, as this will get you the best result from the device on hand and a little post-production can go a long way.Alternatively, you can rent a DSLR camera and appropriate lights. Keep in mind that learning this skill could save you money in the short term, and, if you’re good at it, earn you money in the long term.

Curate your work to include only the best, most relevant photos. It’s better to keep it to five of your best works in multiple angles or detail than to add an additional six works that don’t showcase your best. This can weaken your application. Be the limited British series, keep it short, keep it interesting.

Format your images correctly for submission: check the requirements for resolution, pixel dimensions, and image file size. As the old saying goes: format twice, save once!

Step 5: Put it Into Words

Statements

Writing about your work is different from the initial outline, this is the part about what the work is about. This can be challenging as ideally the work is already communicating what it’s about. So remember that accompanying statements can give context for the project, situating it in your larger practice, and give anyone on the committee who may not have connected to the visual, another opportunity to access your work.

It’s best to start in a way similar to that of making the work: don’t go in with a logical writing plan of intro, thesis, and closing. That’s the road to stilted writing. Instead, sit down and try free-writing. If you need a bit of order to the chaos, the Pomodoro technique can lend structure. Give yourself permission to write absolutely unconnected sentences for ten to fifteen minutes at a time.

Proposal

This is the part of the process when the theoretical why meets the practical how and the definitive where. Revisit these questions you reflected on in your outline and, keeping in mind the audience, expand. It should be clear what you intend to do, and why the reader should be interested in supporting your plan. Statements and Proposals are always written in the first person.

CV

The trick with a curriculum vitae (CV) is to always have one on the go, and edit it regularly. If you don’t have one, do as the saying ironically attributed to Picasso goes: Steal.

Not the contents!

Find a CV aligned to your path that impressively flows from section to section. Take the formatting and make it your own. If you’re an emerging artist, it’s best not to fluff it: focus on impact over line count.

Bio

Some submissions ask for a short bio, this is typically written in the third person and can cover your background, including where you’re from, where you were educated, and some key achievements. It’s the who are you? to the statements’ what are you doing? Use your CV as your guide.

Step 6: Edit

Can you be objective about your own work and writing? Take the first pass and save your friends from you at your most neurotic, grandiose, or nonsensical.

Otherwise the first reader should be a trusted friend or family member who will be honest with you for your own good and keep you from leaving in sentences that mean absolutely nothing. Ideally, editing is a multi-step process that gives a few sensibilities a go at checking tone, intention vs. description, clarity, and structure. Reach out to non-artists to see if your supporting materials can translate across the maker/viewer divide.

You can test all of the above by having a debrief with each editor:

- What did they understand about the work in viewing?

- Did the writing increase the understanding, or muddle it?

- Are there any claims or assertions that need to be challenged?

- What needs to be expanded?

You and your patient friends are also keeping an eye on jargon, buzzwords, and nonsense. Within every generation there are overused, clichéd art speak terms:

Is it juxtaposition? Gen-X

Absence and presence? Millenial

Mark-making? Millennial

Liminal space? You know what, Millennials, we need to have a word (that word is stop-that.)

Though they may fit the work, the meaning these terms once had has long been lost thanks to overuse and misuse; deciding bodies are weary. Find the direct way to say what you’re saying in your own voice.

Now to address the animatronic elephant in the room: AI. This can be a useful tool in editing. Be mindful that professionals reading any kind of submission–proposals, resumes, briefs–have already developed an ear for it. And, if you have ever read a promoted listicle, you have too.

Be selective in your usage; a few editing suggestions for sentences you are struggling with composing is different than prompting ChatGPT to write your entire statement.

Unless, of course, your proposal is an investigation of the intersections of Art and AI and in using it to create your proposal you’re making some kind of meta-statement statement

Additionally, AI-assisted tools like Grammarly can straighten out your wonky syntax and, in some versions, make tone suggestions. It can be the boring friend who doesn’t care about what the project is, but instead how you just switched tenses mid-sentence. If you know this is a weakness of your writing then paying for the full version is akin to the investment in your images.

Step 7. Create a Budget

Once you determine the appropriate call for submission for your project, budget around what is being offered. Don’t make additional demands, but don’t underestimate what the project actually needs—the impression to make is that you are reasonable, realistic, and responsible.

Is the artist-run center offering a fund for framing, marketing material, and reception? Break these elements down, balancing most important to least (hint: reception is the least! Unless this is a relational art experience or performance piece.)

Is it a 25K project creation grant? You are going to get very specific, as this will tell the deciding body that your proposal is well-considered and that not only is the support needed, but that you appreciate what’s being offered and have a plan.

If you’re applying for an exhibition grant, research costs of framing, transportation, and additional items you may need for installation. Residency? Remember that you’re going to have to eat.

Expert tip: Build a margin for the unexpected or for the experimental.

Step 8. Compose Yourself, Get Organized

You may find yourself writing multiple proposals, maybe for more than one type of application. Some artists split their time between producing work and the admin, saving the latter for intense short bursts, ensuring they’re not constantly toggling between those mindsets.

To better keep yourself sane: be organized. Create folders per submission, and make individual files for each piece in each folder. Don’t use the Residency statement for the Grant, don’t use the Exhibition images for the call for acquisitions—they are going to have those small differences that will trip you up and suggest that you’re recklessly playing the funding field.

Step 9. Submit it

Before sending in your packages, whether it’s digitally or by mail, triple-check your list against your documents and images. Leaving yourself time is crucial when there’s rarely an opportunity for additions or corrections.

For artists who put so much—often unnaturally precise—effort into the administrative work of proposals, the panic of pent-up chaos can often come at the end, right before hitting submit.

Take a moment. Check the checklist one last time, open the pdf’s on a few different devices, make sure the image or film extensions match the actual file types, and that codecs are generally agreeable and supported.

Now, breathe.

And… send.

Step 10. A Gift to Future You

During this process there is a good chance you edited out strong supporting media. Maybe it exceeded the image limit or didn’t align with the submission brief or your proposal(s).

The same may go for certain paragraphs or sentences that were brilliant, but unrelated to the project, or were more relevant to another medium you work in, or project that’s not yet at the right stage.You may have made a detailed dream budget for a general grant that could be modified later.

Along with your finished packages, all of these pieces should be kept in their own folder for you to draw from when putting together later proposals.

Future you isn’t the only one to benefit from all the work you just put in! It’s time now to take your best statement, bio, CV, and images and add them to your evergreen package: your website.

Build Your Portfolio With Format

Rated #1 online portfolio builder by artists and makers.

Want more art grant proposal tips? Take a look at our guide to writing great photography grant proposals. Looking for art scholarships instead? Check out our list of best art scholarships.