Applying to art school isn’t just about putting your favorite paintings from high school into a leather tote bag and sending it off. Preparing an application for art and design programs is a meticulous and exhaustive process that takes months, even years, to get right.

When it comes to art school, everything starts with creating an art portfolio.

What is an art portfolio?

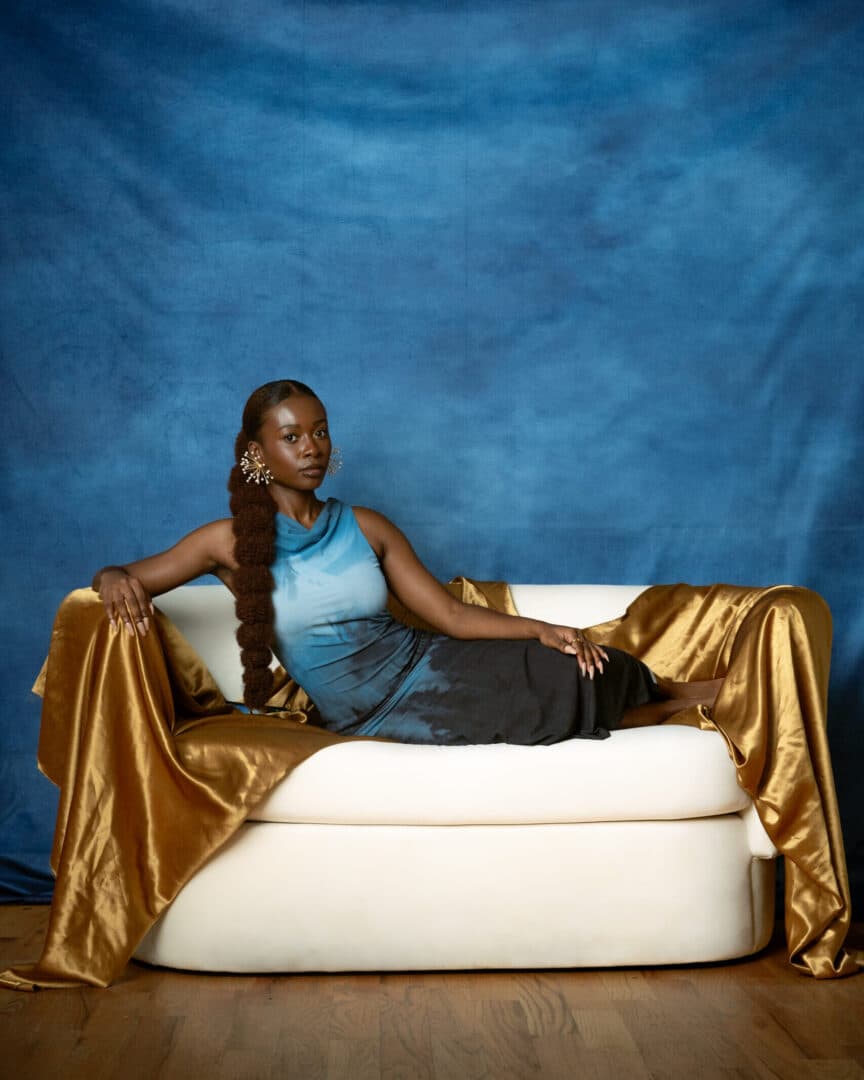

An art school portfolio is a collection of work that represents your abilities, interests, creativity, and overall development as an artist. Whether you’re a painter, illustrator, sculptor, photographer, videographer, graphic designer, or a bit of each, impressing your dream schools requires forethought, a critical eye, and the willingness to share work that’s personal.

Although most art and design institutions evaluate a range of materials—from personal statements, to written tests, to interviews—the portfolio is an indispensable window into your potential and intentions as a student and creative person.

“The most solid portfolios we receive really show a personal, direct, and informed presentation of the applicant’s work, with full knowledge of the program and a passionate, focused reason for why they’re applying to our program specifically,” says comics artist Nathan Fox, who is Chair of the Visual Narrative MFA program at New York’s School of Visual Arts.

There are many crucial steps when deciding how to create an artist portfolio that is effective and impactful. It might seem overwhelming at first, but incorporating the following eleven principles into your process early on can mean the difference between an adequate art school application and an outstanding one.

1. Start building your art portfolio early

If you’re considering applying to art school, it’s essential to start thinking about which media excite you, what your strengths as an artist are, and which programs you’re interested in. You should begin preparing your application immediately, and the best way to start is to get in touch with previous art students and artists who’ve been through the program.

“Creating a portfolio should not be an effort that you have to make entirely on your own,” writes Rhode Island School of Design professor Clara Lieu on her blog, Art Prof. “Visual arts is no different from any other field—you have to get an outside opinion to improve. Take the initiative to get a thorough portfolio critique from an art teacher whose opinion you trust, a professional artist, or an art professor who has experience helping students get into undergraduate programs.”

Getting feedback on your artwork from a variety of mentors is vital because everybody has different ideas about what constitutes good art and what will impress art schools.

“Knowing what people’s sympathies are and what kind of work they’re used to looking at is important for understanding the implications of their critiques,” says Brandon Geib, a graphic designer who recently graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University. “When I was preparing my portfolio, my high school art teacher looked at one of my pieces and said, ‘This is your best work. You should put it at the front.’ Then an art school representative looked at the same piece and said, ‘You could take this out. It doesn’t really matter.’ I had the same experience vice versa with a different project. So there’s a lot of ambiguity.”

Asking several trusted mentors and peers for feedback will go a long way to building an artist portfolio that best represents your work. You’ll want to do this well in advance of your submission deadline so you have time to consider changes.

2. Get familiar with the art school programs you’re applying to

All art and design programs are different, and the type of portfolio they want can vary widely. Reading and re-reading application guidelines throughout the process allows you to cater your portfolio to a specific audience and incorporate their individual requirements as your ideas progress and your work develops.

“Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask questions, copyedit your materials, and ask each program what they are looking for in an applicant,” says Fox. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve talked to applicants who realized they could have asked simple questions beforehand that would have helped them in their decision making and how they applied.”

As well as contacting professors, explore the specific styles of art they teach and produce. “Looking at the work that graduates and faculty are producing not only gives you a good understanding of the type of work a particular school fosters, it also helps you figure out whether you’d like their program,” says Geib. “You could realize, ‘Okay, this is a high-ranked school, but I’m not interested in the work they’re doing.’”

This kind of familiarity also gives you a sense of the educational and artistic community that you’re hoping to join. “When an applicant shows that they really researched what we do in our classroom space, our specific projects, and what our alumni are doing, it says that they’ve taken the time to understand us instead of just reaching for a name or a place,” explains Erin Stine, Director of Undergraduate Admissions at Parsons School of Design.

3. Create original work for your art portfolio

When submitting an art portfolio for college application, schools don’t want to see that you are really good at copying other artists’ work. They want to see that you have your own exciting ideas, and the ability to realize them. A good way to express your originality is to fill your art portfolio with pieces that are clearly unique, whether it’s a work of direct observation or a project that displays novel and inventive thinking.

According to Professor Lieu, when submitting a college art portfolio most of the portfolios that high school students submit to RISD lack direct observational work altogether. “This problem is so prominent that drawing from direct observation is now the rare exception among high school art students. Just doing this one directive will distinguish your work from the crowd, and put you light-years ahead of other students. That means no fan art, no anime, no manga, no celebrity portraits.”

Another way to showcase distinctive work is to create subjects that you find personal and engaging. “In the best-case scenario, a student’s portfolio will be a reflection of their personality, what they’re excited about, and what they’re interested in, and will feel like a visual representation of them,” says Stine. “Of course, we want to see strong technical abilities. But we really want to see what you’re interested in making art and design about, what issues you’re responding to, and how you’re using visual design to explore the world. We’re very open, so the possibilities of what you can submit are quite broad.”

While assembling his application portfolio for art school, printmaker, illustrator, and installation artist Noah Lawrence never worried about whether or not evaluators would like his work. “To me it was, ‘I believe I can do art, which is why I’m applying to this program—here’s the art that I can do,’” says Lawrence, who studied fine arts at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. “That might have been a bit vain, looking back. I never did any research into what portfolios were supposed to look like generally—I just read the program’s criteria and thought, ‘I can do this and more.’” Tailoring your college art portfolio to the specific criteria of the program you’re applying to can be a good way to narrow down the work you include.

4. Experiment with your art portfolio

Every art and design institution will value particular elements of your portfolio over others. But that doesn’t mean they won’t be impressed and excited by something unexpected or unorthodox.

“Within each broad category of art that I featured in my portfolio, like ‘photography’ or even ‘street photography’ or ‘studio photography,’ I tried to get even more specific by experimenting,” says Geib. “For example, I looked at different ways of overlaying and developing film in addition to playing with things like composition.”

One of the benefits of refining your art portfolio over a long period of time is that you don’t have to decide what to put in an art portfolio on your first attempt. Remember, if you go out on a limb and don’t like the final product, you can always redo that particular project. Sometimes the strongest pieces in a body of work are the ones with the most tumultuous development process, requiring many iterations to come to fruition.

“It’s exciting to see that a student has stretched in order to experiment with a type of work or a concept that I’d be unsure about if you described it to me, but that’s really effective when I see it fully realized,” says Stine.

The bottom line: there’s no one answer to the question of what an art portfolio looks like. The contents and presentation will vary from artist to artist.

5. Include artwork that highlights your strengths

Submitting a diverse art portfolio is a great way to let whoever evaluates your work know how excited you are about different types of art. By featuring a wide range of approaches, media, and content, you are showing school admissions officers that you frequently explore a variety of ideas and artistic practices.

School of Visual Art graduate Michelle Nahmad emphasizes that an art school portfolio should act as a gallery and timeline of your abilities and ideas. “Choose pieces that stand as unique beats in the story you’re telling about your work, building on one another to give a sense of your range of abilities and interests,” says the designer, illustrator, and narrative artist.

Lawrence built his art portfolio around the subjects he most wanted to engage with while studying at Emily Carr. “I tried to showcase the skill that I thought I had in each of the classes I wanted to take. I included drawings, paintings, photography, and I even showcased my editing tactics by submitting video montages of myself snowboarding.”

But while a diverse portfolio is a good idea, it isn’t necessary to be an expert in every category before beginning your degree. A common mistake made by hopeful art and design students is submitting substandard work just to appear multidisciplinary.

“I can’t draw or illustrate well at all,” Geib admits. “There are a number of schools that require you to submit still lifes, so that was something that really worried me. At the time it felt risky, but I decided not to submit drawings to programs where that wasn’t a specific requirement. I think that was a good decision. I ended up getting into most of the schools I applied to.”

If you’re applying to RISD, including strong drawings in your application is a must. “Accomplished drawings are the heart of a successful portfolio when applying at the undergraduate level,” says Lieu. “You might have fifteen digital paintings, but none of that will matter if you have poor drawings.”

Institutions like Parsons, on the other hand, don’t have mandatory portfolio checklists for particular kinds of classical media. They’re more interested in whether students are experimenting with both 2D and 3D work, and if they’ve explored digital and video production. “We don’t expect students to share technical work for the sake of technical work,” says Stine. “I would encourage making strong editing choices and really featuring your strengths.”

Most applicants to Parsons select a major, but about ten percent of students enter the program undeclared. Even when portfolios are major-specific, they don’t need to revolve completely around that program. “We have a common first year, and encourage students to explore,” says Stine. “We anticipate that a lot of our students are going to change their major once they get here.”

6. Consider works-in-progress to your art portfolio

Deciding whether or not to include works-in-progress when creating an art portfolio depends a lot on which programs you are applying to. Sometimes admissions departments don’t definitively indicate if unfinished work is appropriate, in which case you are left to decide for yourself if calling attention to your conceptual explorations will benefit your application.

According to Professor Lieu, unless a program requests sketches, applicants can assume that their art portfolio should be largely made up of finished works, with one or two sketchbook pieces at most. “Be sure that everything else in your portfolio is a work that has been one hundred percent fully realized,” she warns. “This means no dirty fingerprints, no ripped edges, no half-finished figures. Many portfolio pieces I see by high school students are only about fifty percent finished and have big problems like glaringly empty backgrounds and lack of detail. The majority of students stop working on their projects prematurely, which leads to works that are unresolved.”

Some institutions, on the other hand, welcome unfinished art. Parsons believes that just as the strongest pieces are often those that took many attempts to develop, providing a window into your creative process can speak volumes about the kind of artist you are.

“Sometimes the final product isn’t the best part of a work—it’s really about what they learned in the middle of it,” says Stine. “We love it when students have these really elaborate sketchbooks with all of these small moments in them. There are ways to incorporate that into a portfolio, and that can really support the student.”

Including unfinished work in your portfolio can be beneficial if you believe that the work offers useful information about your artistic process. Your best bet is to consider whether or not each particular work-in-progress really adds something to your portfolio. Don’t just include incomplete sketches for the sake of bulking up your submission. It’s better to have a smaller, more refined art portfolio than a larger one with lower-quality works.

7. Portfolio curation is everything for college portfolios

It’s now time to cull out the best and most diverse pieces from your personal collection to present in your final portfolio. For each project, select only the specific and unique things you can bring to it. For instance, if you have multiple projects each with the same approach, include only the strongest one. An art portfolio is like an essay – presenting ideas must be comprehensible and succinct.

An art school portfolio is about pushing the limits of art and design throughout your work. One approach could be to select work that takes advantage of those mediums you’ve selected.It can look like this: select photos that portray the world differently than paintings, or paintings that achieve something drawings are incapable of, and so on. This way of refining your collection guarantees that each piece is unique while also conveying your rationale for using each medium.

Professor Lieu says most applicants don’t take full advantage of what drawing can offer in their portfolios for college. “The vast majority of high school students are creating tight, conservative, photorealistic pencil drawings drawn from photographs,” she explains. “Drawing is not just about copying a photograph as accurately as possible; we now have cameras that can do this instantly with incredible precision and quality. Ask yourself what you can express with your drawing that a camera would not be capable of producing by itself.”

Exhibiting the strengths and capabilities of particular styles of art also means experimenting with the different media that are available. For example, instead of drawing with pencil, try doing that same study with crayons, pastels, charcoal, chalk, or ink.

“Charcoal, in particular, is a great drawing material because it motivates students to develop an approach to drawing that is bolder and more physically engaging,” says Lieu. “Just using these drawing materials will distinguish you from the other student portfolios, and will inspire you to experiment with drawing in a bolder and looser manner.”

8. Effectively document your art portfolio work

The way you document your art, whether it’s with photographs, video, or scans, can make or break your application. In many cases, this documentation will be the only account of your work that an admissions department is exposed to.

“Documenting your work is a practice that will be continually emphasized as you move through school and continue in your career,” says Nahmad. “It will hopefully become second nature and tailored to your process. Depending on your skillset and the kind of work you’re aiming to record, your documentation might also require that you seek outside assistance.”

Although photography is the most traditional medium for capturing static art, don’t be afraid to go the most suitable route you can think of.

“Sometimes video can be the most effective way to capture something that you’ve made,” says Stine. “For instance, if you have a 3D object or something that you have to interact with, instead of taking a bunch of still images, take a quick 360-degree video of it. The same thing goes for books or zines—rather than stressing about taking up your whole portfolio with a series of images, why not make a 30-second iMovie that goes through the extent of what you did?”

Professional art photography is extremely expensive. Luckily, you can take more than adequate photos of your work with a little planning and minor equipment. If you’re shooting your own art, the most important elements to consider are even lighting, accurate color replication, sharp focus, and capturing high-resolution images.

Photographing pure white in an artwork that also contains darker colors can be tricky. The key is using at least 250-watt lights, placed at even intervals surrounding the surface that you want to render.

“These lighting kits aren’t super cheap, but regular incandescent and fluorescent lighting is not sufficient to produce high-quality photographs,” cautions Lieu. “Regular lights will not produce the color accurately, and you will not get good focus because the lights are not bright enough.”

You may be able to use equipment that is already at your school if you are currently in high school or college. If you are not a student, you may want to rent or borrow photographic equipment for the day. Depending on what kind of work you make, scanning images may be more appropriate than photographing.

For non-students, local print shops will have low-cost scanners available. if your portfolio contains drawings or collages, photos can show the details better. If your portfolio contains analog photography, be sure that the prints or scans you include are high quality. When getting prints or scans done at a lab, ensure that the photos are the best representation of your work.

9. Attend National Portfolio Day

Juggling all of these tips might seem like a difficult task on top of trying to complete your high school education—or working, if you’re a high school grad. National Portfolio Day was created to make it easier for prospective art students to get portfolio feedback. It’s an opportunity for students to discuss their art portfolios in person with representatives from schools all over North America.

A university fair-style event, National Portfolio Day offers the chance for you to have your portfolio critiqued by virtually every undergraduate art and design program in the United States and Canada before you apply. Between September 2017 and January 2018, NPD held events in forty-two cities across the continent, plus an online session for those who couldn’t make it in person.

“I would definitely advise that everyone applying to art school go to National Portfolio Day, especially anyone debating about whether or not they want to apply,” recommends Geib. “It’s easy to get trapped in what your two high school art teachers think. There’s a lot more variety of opinion and insight out there. Some of the school reps at the event looked through my portfolio and basically said, ‘As long as your GPA and basic college entrance requirements are met, your portfolio is good enough to go to our school.’’’

However, be prepared for honest and even jarring critiques of your work too. “I definitely got some pretty harsh criticism as well,” Geib says. “But you have to be able to separate yourself from your work, otherwise you’re going to get beat up emotionally when people are trying to help you improve your work overall. You have to be able to say, ‘This is something I created, not me as a person.’”

If you’re going to attend an NPD event, make sure to arrive early, as entrance lineups can get extremely long, and sometimes the organization turns people away altogether because of limited capacity.

“If you’re really serious about being accepted into a high caliber undergraduate art program, this is the event to go to,” says Lieu. “I recommend going in the fall of your junior year, just to get a feel for things, and then again in the fall of your senior year.”

10. Think about the big picture beyond your portfolio

Meeting these criteria for a successful application portfolio will greatly increase your chances of getting accepted to the art or design school of your choosing. The last piece of the puzzle is asking yourself, “Does my art school portfolio truly represent why I want to make art?”

You may feel like you are making art to meet admissions requirements for a professor or critics during this long process. Remember what drew you to art school, and think of how art school will continue to enrich that relationship.

“One of the most popular quotes about creativity is ‘Good artists borrow; great artists steal.’ There’s a lot of debate about it, but I think essentially it means don’t try to fulfill other people’s expectations with your art,” says Lawrence. “You have to ask yourself whether you’re making art from yourself or for other people. When I made my portfolio, I started by immersing myself in other people’s work and the prompts the schools gave. But ultimately, I tried to forget about all of that and make art that excited me.” Make sure you know why you want to study art at a post-secondary institution before clicking the “Submit”. “It’s truly evident in their application materials if applicants aren’t really aware of what they are applying for and why,” says Professor Fox. “We invest in our students as much as they do, and expect the same in return from all applicants.”

In 2021, art school applications are at an all-time high. With online applications and global interconnectivity, it might seem like studying art is simpler than ever before. However, more opportunities means more competition.

Nonetheless, having a good sense of why art matters to you really comes across in your portfolio. It says that you’re ready to give it your all, and sets you apart from other prospective students.

Art Student Portfolio: How To Get Into Art School

As you can probably see from this list, getting into art school takes time, dedication, and patience. In particular, creating an art portfolio that is well thought out and intentionally put together is one of the biggest factors influencing your acceptance into your school of choice.

As mentioned, we recommend taking your time, being intentional with what you include in your portfolio, and being clear about the guidelines from the schools you are applying to.

While we understand that applying to art school can be overwhelming, we hope this guide gives you the confidence you need to put together an impactful portfolio that gets you started on your path to pursuing your passion.