If you are giving serious thought to applying for an undergraduate program in visual arts, you have probably wondered what review committees look for in a portfolio submission. Let’s move past outdated advice and break down some simple suggestions so you can present yourself with confidence.

Read the Requirements

I cannot stress enough how important it is to read and follow the actual instructions or requirements for your specific program. Yes, you are probably applying to a large number of universities to widen your net, and yes you will be using the same portfolio for each application. HOWEVER, each program is unique and the requirements and what they are specifically looking for will vary slightly from program to program.

For instance, Concordia University’s Studio Art program asks for a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 20 items while York University’s Visual Art program requires only 8 items including a sketchbook. You have way less room to showcase who you are as an artist with 8 artworks vs 20! So the range of images and artworks you need to prepare will be vast depending on where you want to apply. Additionally, Emily Carr University of Art & Design requires a Studio & Writing Assignment with very specific prompts in addition to the portfolio.

Strangely, the University of Guelph’s undergraduate Studio Arts program doesn’t even require a portfolio for admission!

Proper Documentation

A make or break aspect of a portfolio submission is ultimately based on the quality of the artwork, exemplifying the creativity, unique perspective and innovation of the artist. However, if we can’t clearly see your artwork in your documentation, the submission is essentially useless.

I have seen many submissions where the artwork itself (whether it be a painstakingly laboriously-made textile, or large painted mural or shiny and detailed ceramic) loses its lustre and detail in dark, uncropped, blurry or chaotic images.

Here are a few points to stick to when thinking about proper photo documentation:

- Camera: Use a camera you have at hand, it can be your smartphone or a fancy DSLR, whatever you use, stay consistent.

- Setup: Create a single session where you can photograph all the artworks that are going into the portfolio so that there is consistency in lighting, colour values and background. Choose a neutral or white/light background to photograph paintings. For three dimensional artworks use a white or neutral piece of fabric and drape over a tabletop to create a seamless background.

- Lighting: Daylight from a window (preferably with a soft white curtain to diffuse the light) will be your best DIY option but you can also rent studio lights or pick up some daylight balanced clamp lights at Home Depot if budget is limited.

- Angles: Take several shots of a single artwork, even if it is two dimensional. Take a single, straight-on photograph, one side angle and a closeup detail as this gives the reviewer a sense of scale, context and materiality.

For more instructions on documenting your art, we have a detailed guide HERE.

Choosing the Artworks: Editing and Sequencing

Depending on how you want to represent yourself visually or the kind of statement you are making to the committee, there are generally two distinct approaches to selecting, sequencing and editing artworks for your portfolio:

- The Greatest Hits Strategy: a selection of artworks form a range of projects, mediums and styles that have little to no connection to one another but illustrate a breadth and strength of individual works.

- Tight Unified Vision Approach: a tighter selection of artworks from only one or two bodies of work, connected thematically or aesthetically, that illustrate strength of the artist’s vision, individuality and style.

While there is no one right answer on how to proceed, there is a Goldilocks just-right-zone where you somehow magically blend both strategies into a single portfolio; You are being asked to at once be varied in a wide range of disciplines but also highly technically skilled in one or two specific ones. You need to show you are a thoughtful critical thinker while also balancing emotional intuition and empathy. And finally, demonstrate that you can be playful and exploratory but also have a clear vision and the beginnings of a style.

Some Overarching Notes

Despite whatever strategy you choose, here are some helpful notes on how to sequence your images.

- Less is More. If you have 3 or 4 of the same kind of paintings or sculpture, keep the strongest. When you add more to a series, it actually doesn’t strengthen the message, it weakens it.

- Tell a Story. When selecting artworks, think of a story that each work is telling and connect them in a meaningful way. While organizing the flow chronologically might make literal sense–you made this piece after this one, etc, the greater impact on the viewer might be in arranging the works to emphasize their thematic or visual concerns

- A Strong Edit. When sequencing, think about creating a strong tight edit where every piece has a purpose in building momentum and telling a new piece of information or emotional resonance. Ask yourself if I removed this one piece, does it feel like something is missing or are there gaps in the storytelling?

Process and Sketchbooks

While you may think that your sketchbook and discarded works in process are of little or no value as part of your submission; they’re actually vital.

Sketchbooks or collections of in-progress work are highly valuable documents that, to the faculty and evaluators, speak about who you are as an artist, thinker and maker. Though you might feel trepidation in sharing incomplete work, sketches, and maquettes that aren’t necessarily as strong as “finished” work, be comforted by the knowledge that evaluators are looking for something specific. We want to follow along on your explorations, failures, dead-ends, and experimentation as we try to understand how you operate as a maker.

As Evaluators, we ask some questions about the work:

- Is your process iterative?

- Are there various conceptual or visual threads flowing?

- What are the inspirations or research used?

- Can we see how your inspirations get transformed through your path of exploration?

- Are there direct observations of the real world, how are those observations translated?

- Was this an assignment or heavily coached by an instructor? Or was it made outside of class time?

- Can you work independently and follow your natural instincts, prompts and interest without assigned parameters from a teacher?

With this in mind, think carefully and include drawings, photographs, video clips, posters, creative writing, research articles, story development or anything that is an important piece of visual ephemera that helps guide your practice.

Studio Assignment or Prompt

Although not as common, there are some programs that require a specific studio assignment, or home test in addition to your portfolio. This is a specific artwork you will make following instructions or prompts given by that university. For instance, in Canada, ECUAD’s studio assignment lets you choose from something clearly defined, like creating a portrait, or as open as “Create something that reflects on the environment where you live, whether it be your home, your neighbourhood, your geographic location.” Other programs in the USA like Cooper Union’s BFA program require a home test, for which an instruction will be sent out to applicants one week before the application deadline. When applying for multiple programs, be prepared to make an artwork with limited preparation and time.

Statements and Descriptions

Over the years, Studio Art programs have become responsive to feedback that the academic writing component can be an obstacle or barrier to entry, especially to young artists who feel more comfortable expressing themselves visually rather than textually. As a result, the writing component has changed dramatically to be less academic and more accessible. The statement should be kept brief at 250-800 words and generally confined to the parameters of answering who you are as an artist and why you want to enrol in that specific program. So while you can “recycle” your artist statement for each application, there will be a significant amount of tailoring you will need to do to make it authentic for that unique program.

Include Unique Details

Mention information and offerings that are specific to that university. For instance, York University in Toronto, Canada, has one of the last working metal foundries and a rigorous sculpture studio that is particularly rare. This would be a huge motivating factor to mention in your writing if you are interested in developing your sculpture, mold making, and metalwork skills.

Research the Faculty

Is there a specific artist or professor that you want to work with or learn from? Include their name and any details about their art practice that is relevant to you. This illustrates that you are a good match to the program’s values and teaching philosophy.

Be Yourself

Write in your own voice using your own language, references and ideas; don’t give into the pressure to reference or cite academic texts or other artists. Ultimately it will come across as disingenuous and not well-suited to the artwork presented in the portfolio. The evaluators are keen to understand your background and influences so just be honest and confident in who you are, that will come through in the writing as well as the artwork.

Descriptions

Almost all undergraduate programs use Slideroom as an intake tool for portfolio submissions. It’s a good idea to get to know this platform. It’s a simple way of submitting JPEGs with captions and text, so be sure to include details on the dimensions, media, title, and date for each piece of finished work you submit in addition to a few sentences (no more) about the work, your influences or intentions, what you learned or any information you think is valuable for the evaluators to know. Even just including a title for each piece really helps the evaluator understand where you’re coming from and can open up possibilities on how to interpret the artwork.

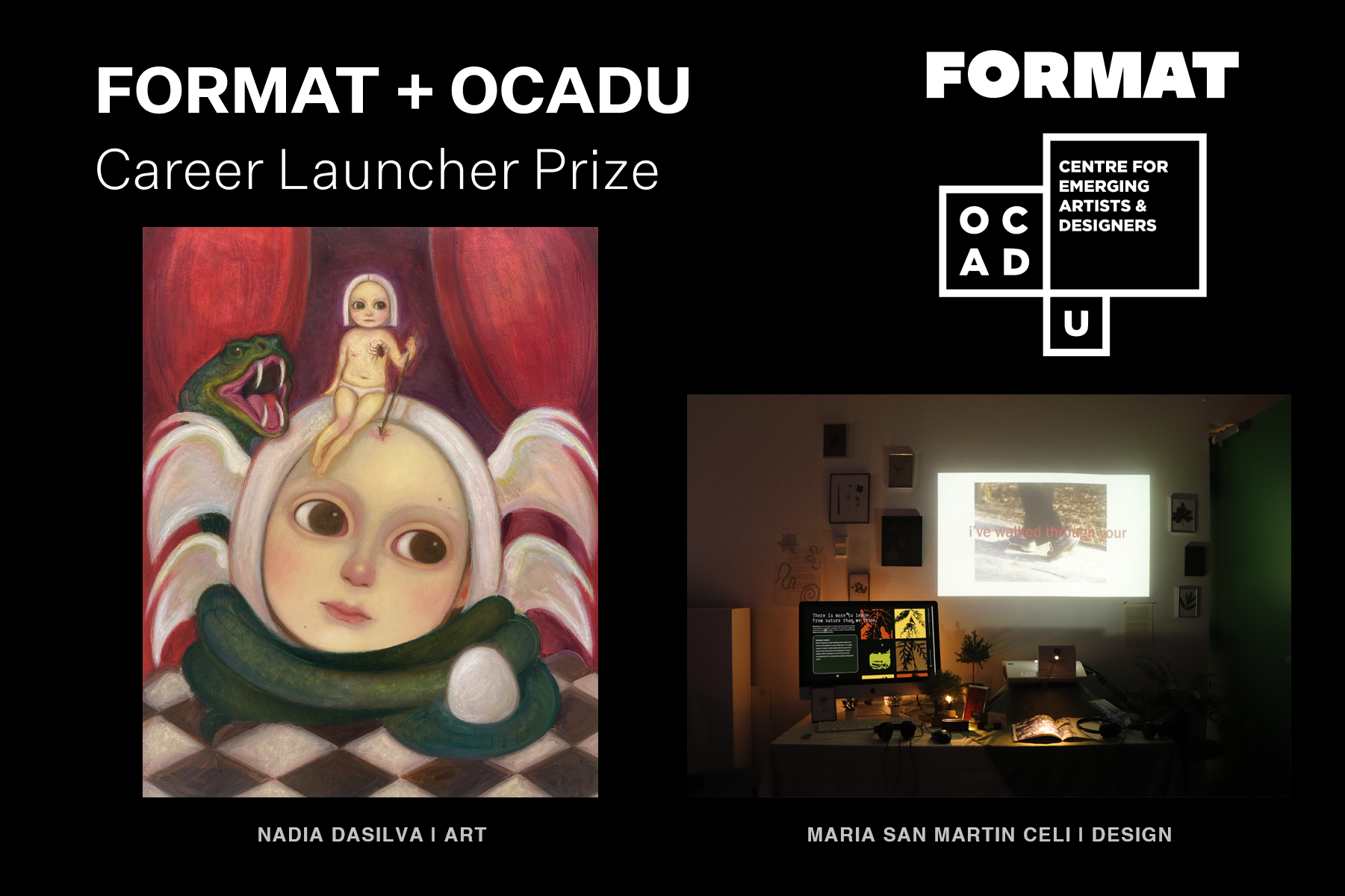

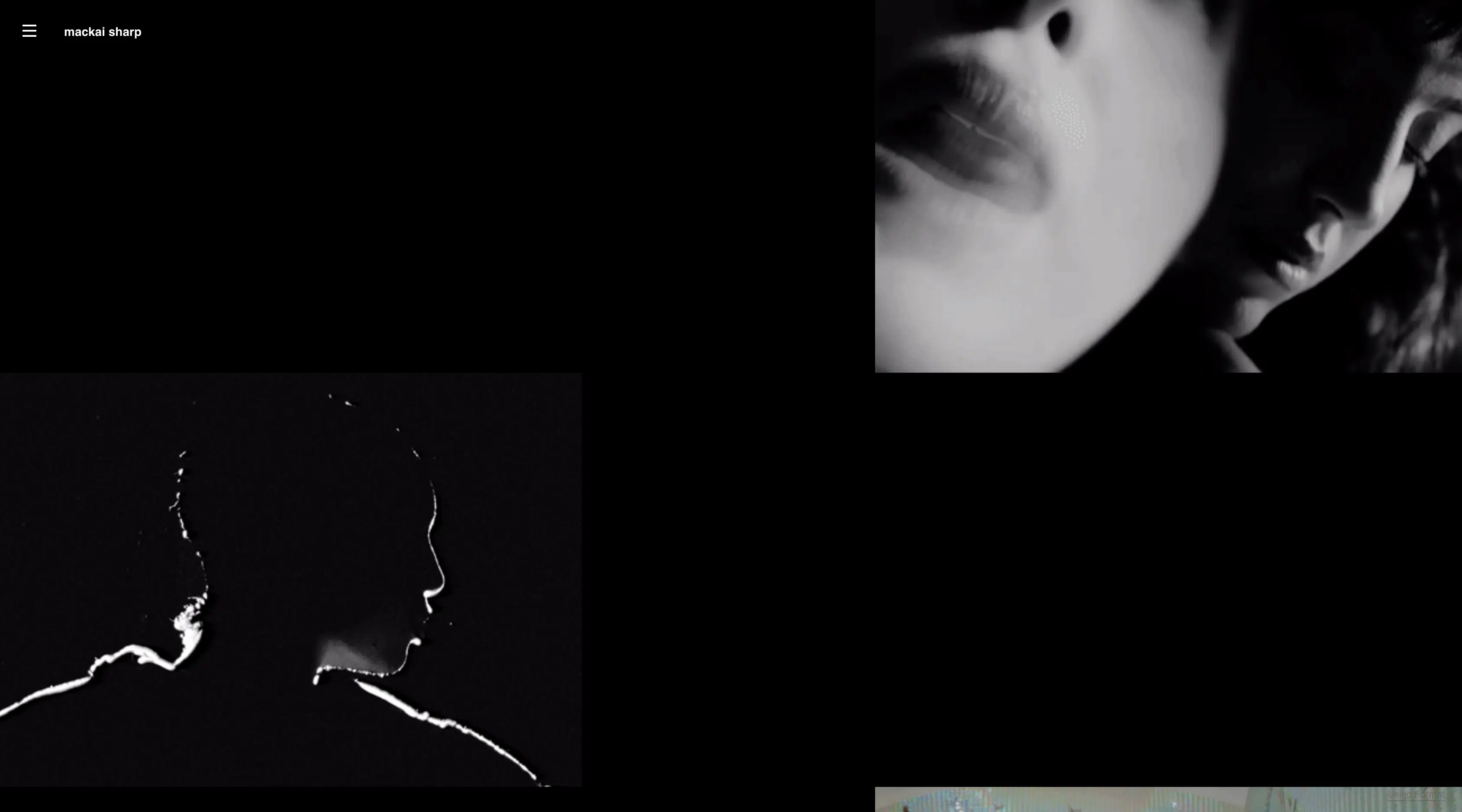

Bonus: a Portfolio Website

Building a portfolio website to showcase the best of your work online is also a way to demonstrate that you’re serious about your continuing art practice outside of high school. The Format platform has a unique education program to get students started on their creative journey. Establishing a website can also be a great way, when the application is limited to very few images, to let evaluators see more of your work if they’re curious.

What Are We Looking For?

You might feel overwhelmed or confused by all the advice listed above or given to you by teachers, guidance counselors or recruiters. As you assimilate all the tips and suggestions, it might seem some tips are counter-intuitive or directly contrary to some of these suggestions.

There is real merit in going with your gut feeling and doing what feels best for you. Listening to your inner voice and developing confidence in how you present your work to the world is the biggest and most important skill to hone throughout this process.

All in all, we are looking for imagination, creative thinking and an individual point of view that shows the potential of the artist. We don’t expect you to be fully realized with highly skilled techniques and fancy words. Speak in your own voice, show work you are proud of and that strength will shine through in the portfolio regardless of how it was edited, written or displayed. While it can often seem trite, the best advice I can give is be yourself; you are the expert in your own work, no one else.