As an emerging artist, or even as a mid-career professional, planning for retirement probably isn’t at the top of your to-do list—let alone creating a will. It’s all too easy to put off this kind of planning, or to dismiss your estate as something artists don’t need to worry about. But deciding what happens to your artwork after you’re gone is important.

After his 1970 death, the artist Mark Rothko’s friends and family became entangled in a years-long debate over his works, demonstrating the necessity of creating an estate as an artist. ‘‘It opened artists’ eyes to the concept that this was a business, not just an intellectual world,’’ his daughter Kate Rothko told the New York Times of the very public legal battle. The case of Vivian Maier highlights the importance of estate planning even for those of us who aren’t necessarily world-renowned artists. An amateur photographer who died with no will or estate, Maier became famous when her work was discovered after her 2009 death, leading to a series of legal battles over who exactly has rights to distribute her work.

Copyright expert and director of The Institute for Artists’ Estates Loretta Würtenberger is trying to make it easier for artists at all stages of their careers to make sure their work is always in safe hands. Along with lawyer Karl von Trott, Würtenberger published The Artist’s Estate: A Handbook For Artists, Executors and Heirs, the first comprehensive guide on the subject. The book full of advice on how to manage and maintain the works, archives, and ephemera of a deceased artist, as well as how an artist can get their affairs in order while still alive.

We got in touch with Von Trott to ask for his advice on what you, as a living artist, can do to preserve your work, legacy, and artistic vision.

Format: First of all, can you explain what constitutes an artist’s estate? In your book, you say in the legal sense, an estate can encompass literally anything that the artist leaves behind when they die.

Karl von Trott: As Degas put it, “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” The physical artwork in most cases is only one component of an artist’s legacy. Sources for understanding and contextualization, e.g. correspondence, newspapers, objects, and artwork of friends and peers are another integral part of an artist’s legacy. But there is no irrevocable rule telling you what exactly you are working with when taking care of one. So the meaning of the word is fluid.

The legal point of view is different. It is important to be precise here. The use of the term ‘artist’s estate’ can be misinterpreted, depending on the context. Because the term ‘estate’ has a specific legal meaning in the common law jurisdictions.

On the one hand, it can refer to a common law legal structure, which all assets of a natural person go into at the time of death. This structure is usually temporary. It is liable to pay inheritance taxes and handle the inheritance via an executor. After this has been done, the assets are transferred to the heirs. So it stands for a purely legal concept.

On the other hand the term ‘artist’s estate’ is broad, and generally used to describe a person, or an entity who is in charge of the legacy, in all possible ways, irrespective of the legal nature, the form of the organization, the planned duration, etcetera. So in the end, the term is used to mean that which builds a bridge to the deceased artist and makes sure that their work goes on!

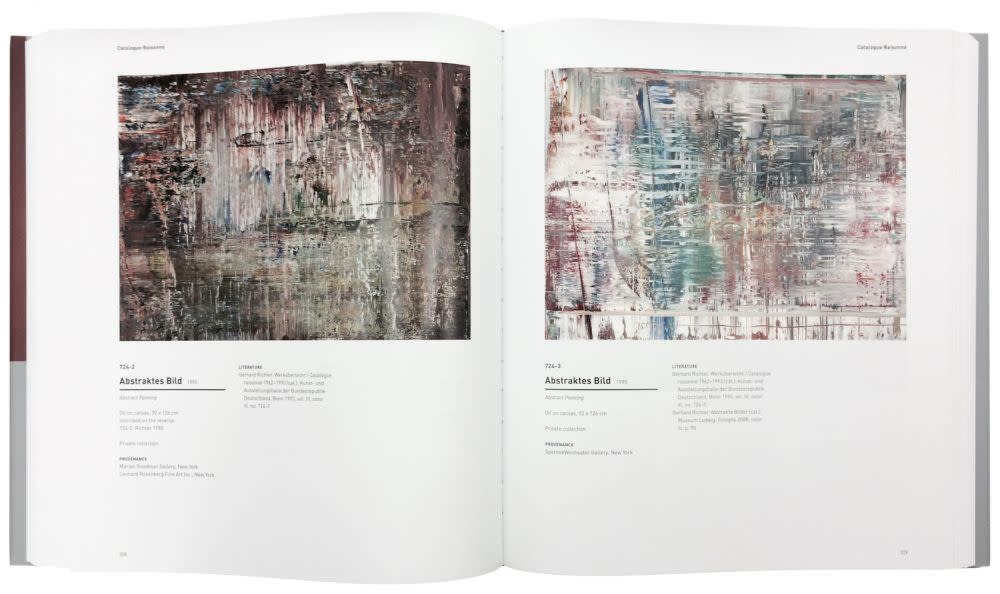

Gehard Richter’s Catalogue Raisonné Vol 4, via Ursus Books.

Do you think that artists should worry about every scrap of paper, every note that has ever been scribbled on? Where do you draw the line of what to include in an estate?

In the end it is a personal question. It is not on me to decide what an artist should do, what to include in a body of work and what not to. But ideally, the artist has a clear vision and gives direction to those who are ‘continuing’ their endeavor.

The most obvious way to do this is to define the body of work by destroying those creations which the artist does not consider to be part of his artistic expression. With regard to the artworks which are not in the artist’s possession anymore, the artist could determine that these pieces should therefore not be included in the future catalogue raisonné. Gerhard Richter has done this for completed works, dating before his first catalogue raisonné artwork Tisch, from 1962.

If the artist is not able to filter his oeuvre by destruction, he should at least define and categorize his artworks in relation to the future legacy work as well as give a manual for post production and installation. They should cover questions like:

What is a finished artwork? What is an unfinished artwork? What is allowed to leave the internal sphere of the estate for loans and exhibitions? What not? What is for sale, what is not, and if for sale, to whom? In case of installations: how is the work to be installed to maintain integrity? By whom? In case of sculptures and prints: is posthumous editing desired? To which degree?

It might be helpful to see this task as a great final artwork itself, the ultimate Gesamtkunstwerk.

Most people will be wondering, what’s the point? To ask frankly: why should a mid-level, 20- to 40-year-old artist care?

Every artist should care. Nobody can foresee how life goes, especially not how long it may go for. It makes things tremendously easier for those who are later entrusted with taking care of an estate if the artist thinks about the legacy early on, or at least once in awhile, and puts something down on paper. Not necessarily a comprehensive will, but some rough statements about the desired posthumous dealing with his oeuvre. This will give direction for the future caretakers in case of an untimely death.

I know that it’s tough to deal with the topic of passing away at any point in time, but any form of guidance, an inventory and good studio organization will be highly appreciated by those in charge later on. It saves time and money and will mean the work and the legacy are more likely to succeed.

So say a living artist wants to create an estate, what are the things they should keep in mind, or the first things they should do?

An artist’s legacy has two sides. There is the formal one, concerning the legal and and tax structure, and there is the content and art-related side. Both sides, of course, interlock. Like with every heritage that is left behind, the divisor must at first make up his mind and find answers to elementary questions:

Shall my beloved ones benefit from my residues? If yes, who, and in which way? How can I combine it with the posthumous work for my oeuvre? Do I want an institutionalized legacy tool? Can I afford it? What will be its purpose and at which point in time? Who will do the job, and for how long? What will be the assets to create revenue streams for the legacy work? And subsequently, what is the best legal and fiscal structure to reach these objectives?

Again, as mentioned above, many of these questions should ideally be answered during the artist’s lifetime. It will be a huge relief to those who are left behind.

Thomas Schütte’s Skulpturenhalle, image via Thomas Schütte Stiftung.

Tony Cragg’s Sculpture Park in Wuppertal, Germany.

Can we talk a bit about Thomas Schütte’s museum that he has built to display his sculptures? This is a brilliant idea, but not many artists have this financial ability. What else could someone do to preserve or display their work in the way they want?

Indeed a brilliant idea by Thomas Schütte. The number of artists becoming sensitized to the issue is growing. Tony Cragg, Damien Hirst, and Hiroshi Sugimoto are other good examples. They, too, have set up a showroom/museum-like structure not only to exhibit their own work but to support other artists. Without their personal commercial success, this of course would not have been possible. But even these art world titans have to have a strategy regarding long-term economic sustainability and an overall purpose of their legacy vehicles.

All artists can start by asking themselves these questions: answering the questions from above relating to the body of work, write the answers down, prepare all files professionally and make sure that the artwork and archive material is physically preserved. Find someone who will take care of the legacy, on at least a basic level.

From there everything might fall into place! It also depends on the commitment of the caretaker, the assessment of the art historical importance of the oeuvre, and of course the ever-needed amount of luck. The more supporters the caretaker finds, the higher the chances of preservation and visibility of the work. These caretakers can be curators, gallerists, or journalists.

Unfortunately, there are no standard solutions. Museums are more and more reluctant to take over artist’s estates, and if at all, they take over well-structured, partial estates. In Germany we have seen a rise in especially regional non-profits who address this issue, but here again, like in a museum, their capacities are limited.

Marisol Escobar’s New York studio, image via Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

What is your opinion on Marisol Escobar gifting her entire collection (not to mention house and studio) to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in New York? Are museums equipped to possess the entire oeuvre of an artist? Do you think such a large institution can do the work justice when they have so many other programs and focuses?

It depends on the individual case, the museum, the people involved, etcetera. I am sure the Albright-Knox museum will do a great job in this regard. It supported her work early on and I assume both sides were able to prepare and structure the bequest professionally. From the artist’s perspective, it is key to involve the respective institution early on, to get a sense of what it can do, wants to do and especially what it does not. Then, one should define the conditions.

The danger with whole single museums taking over estates is that the artist’s legacy and the art becomes static, for the reasons you mentioned, and because the art is centered all in one place. But I think in the case of Marisol Escobar, having her studio in New York is a great chance for the museum to avoid a scenario like that.

I keep thinking about how this is relevant for digital artists… Do you imagine a video artist’s legacy being archived or cared for in a different way to that of a sculptor’s, for example? Are there different ways to handle estates for different mediums?

No, I don’t think so. Of course the archiving technology might differ and the question of data preservation is a more vital one for digital artists. But in the end, the medium does not define the tasks of an artist’s estate manager which is: to keep the artist’s ideas alive, push the art out there, let it make people think, see, understand and react, and to improve the individual’s life and the world as a whole.

Cover image by Alex Stoddard.