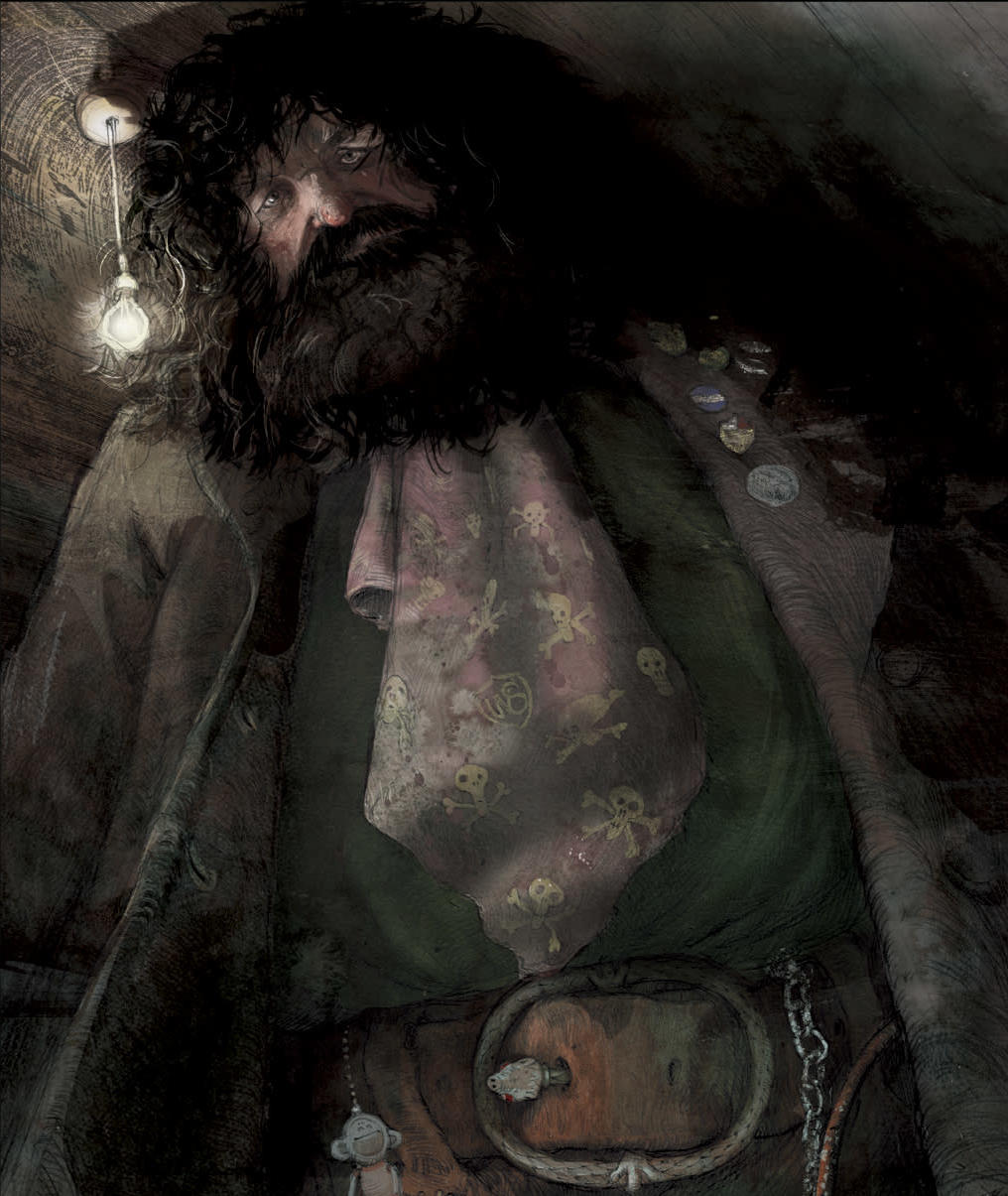

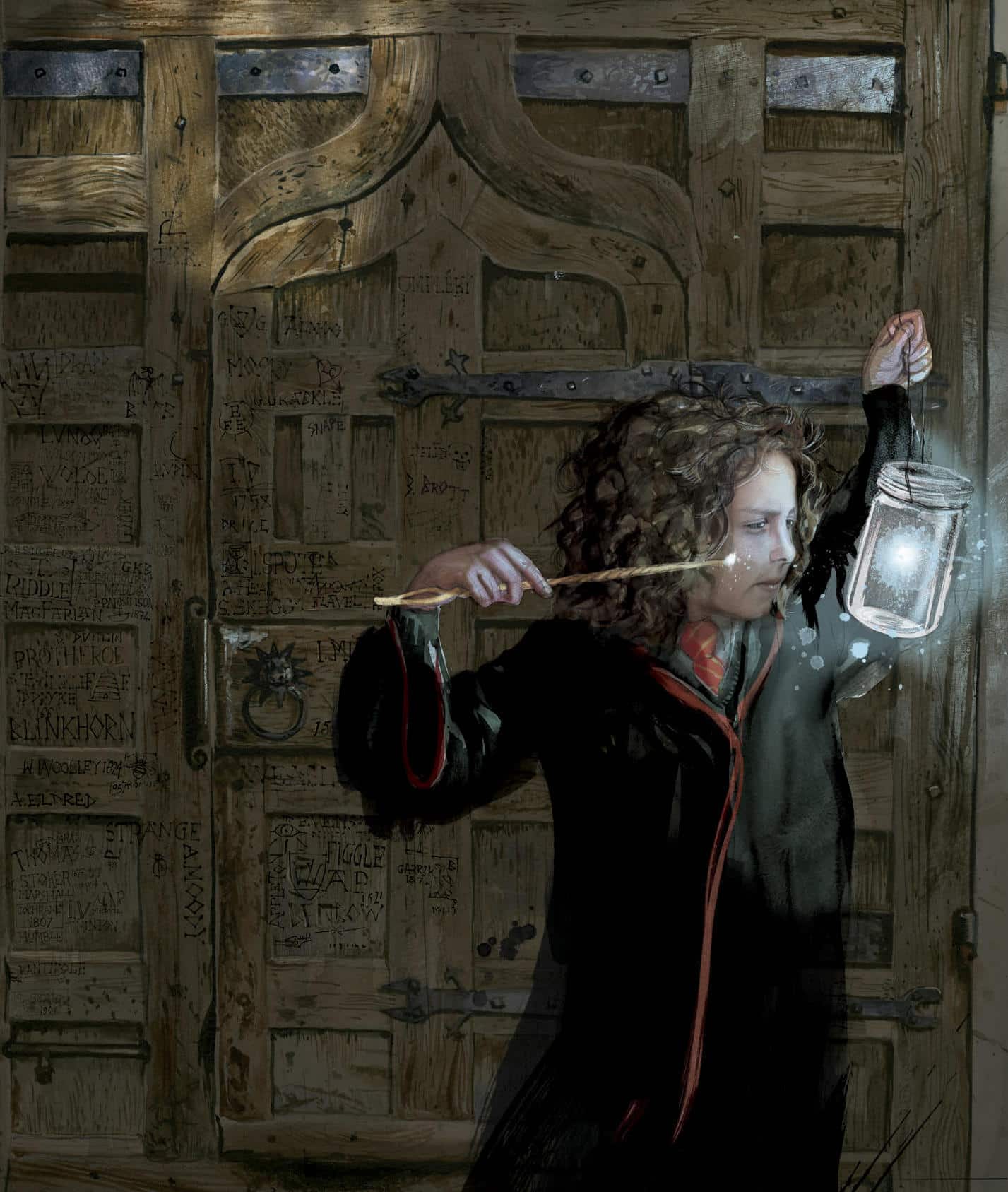

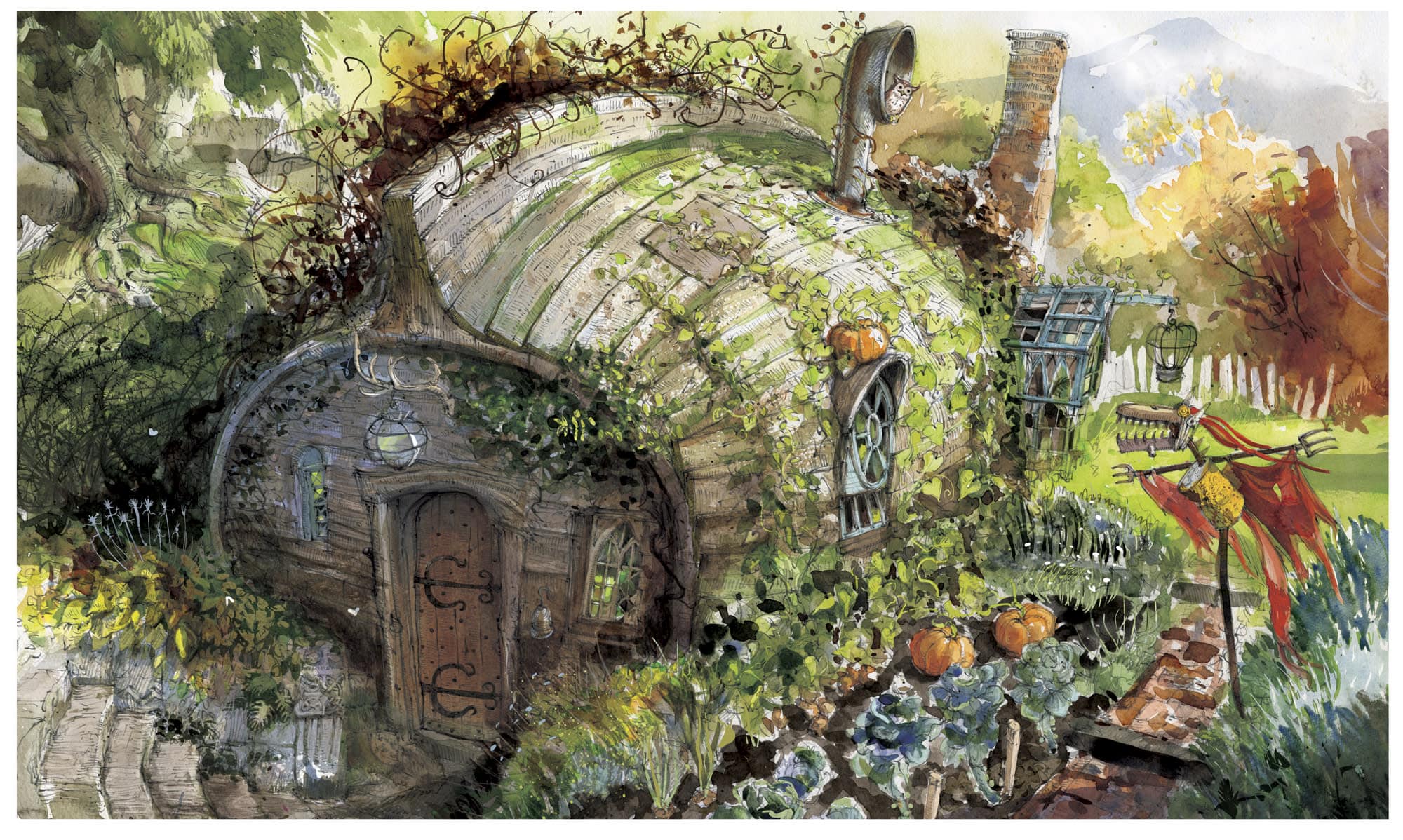

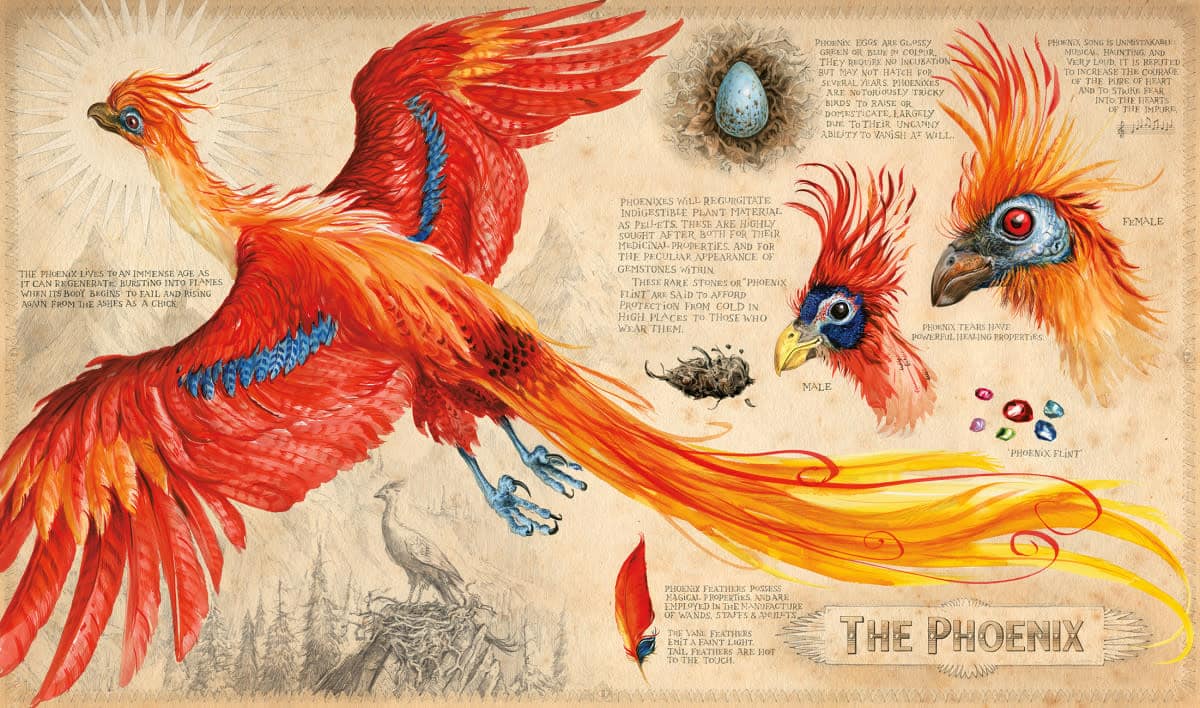

Of the many different illustrations of Harry Potter, Jim Kay’s artwork for The Harry Potter Illustrated Editions is perhaps the most detailed and heartfelt, and certainly the most prolific. Creating over a hundred images per book, the British illustrator’s renderings of our favourite witches, wizards, and magical locales are not only wonderfully vivid and technically impressive—they bring a breathtaking individuality to J.K. Rowling’s classic series that’s hard to describe.

“As well as faithfully representing the text, you’re trying to expand the world sideways and make the reader feel like it goes beyond what’s framed by the covers of the book,” Kay says. Bringing something new to the most successful book series in history and following up the box office-topping Harry Potter film adaptations takes real imagination, not to mention guts. Luckily, Mr. Kay is just the illustrator for the job.

Since Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone Illustrated Edition hit stores in 2015, and was joined a year later by The Chamber of Secrets, both have enjoyed excellent sales and Kay’s potent drawings have been widely acclaimed. The third installment in the series, The Prisoner of Azkaban, will be released on October 3rd, followed by the debut of Harry Potter: A History of Magic, an exhibition showcasing original drafts and sketches by Rowling and Kay, which opens in London at the British Library on October 20th.

In celebration of Harry Potter’s 20th anniversary, we had the pleasure of talking with Jim Kay about his journey into the depths of Rowling’s world, life post-Brexit, and the blood, sweat, and tears of illustrating.

Format: What stands out most about your work for The Harry Potter Illustrated Editions is a sense of emotional realism. Your characters feel so quirky and human. How did you decide on a sensibility for your illustrations?

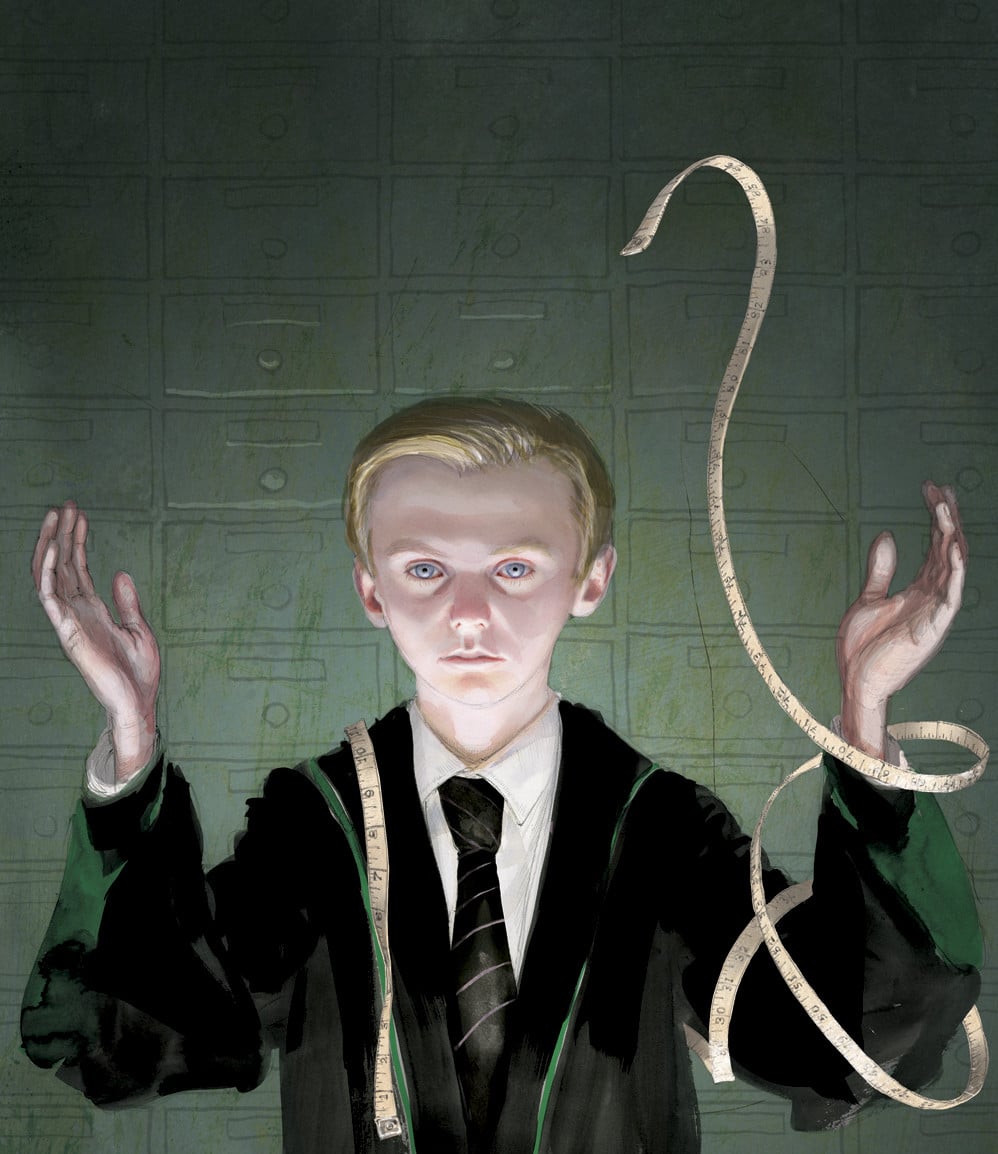

Jim Kay: That’s very difficult to say. When it was announced to the public that I’d be illustrating the series, people started asking me about it, and it hit me that this book matters to a lot of people. At first, the characters were all wrong, because I was trying to predict what everyone expected illustrations of Harry Potter characters to look like. Then I just started reading and rereading the text.

I use this big ring binder the publisher made, called the Harry Potter Bible, which lists all the mentions of everything—from color, to clothing, to sweets, to magic, to food, to every single spell, to every single book published in the wizarding world. The descriptions of the characters are very meager. It’s usually the same repeating key words.

For instance, I think for Neville the only description is “an oval face.” It’s more about their role in the story. So you’re trying to build a mental character rather than a physical one, and then finding a model that inhabits that character.

I still don’t think I’ve got Harry right. Everyone has their own idea of what Harry should look like.

What do you see in Harry’s character, and what did you look for in the model you chose for him?

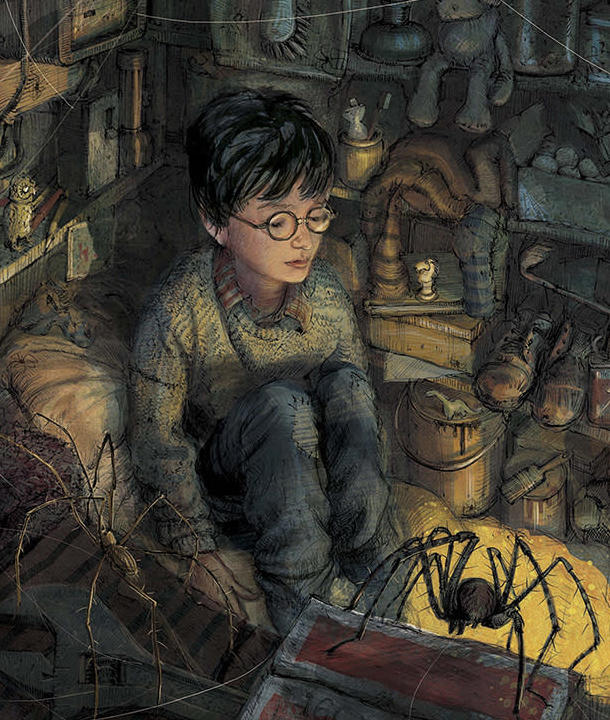

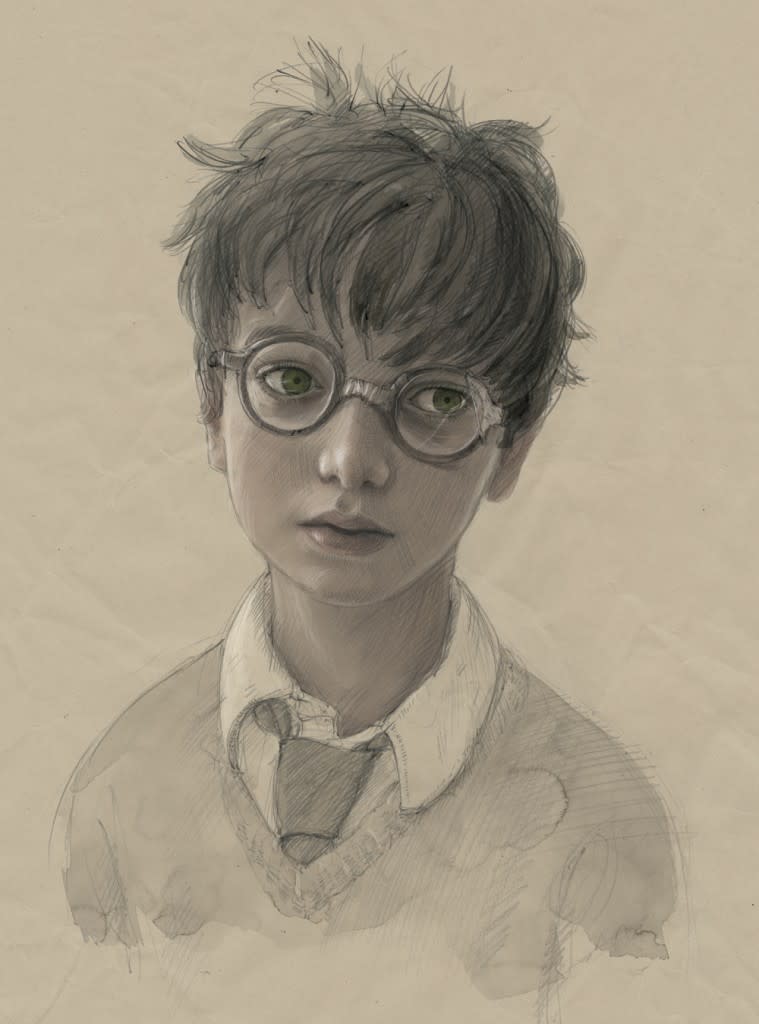

I still don’t think I’ve got Harry right. Everyone has their own idea of what Harry should look like. For me, it was a Blitz kid during World War II. There are photographs of these lost-looking, scruffy young children with thick glasses being put on trains to safer parts of Britain while the Blitz was falling on London. The model I use for Harry is a young boy I saw travelling with his mum on the London underground one day. He just looked different—he has very large eyes and is quite striking. I didn’t want a stereotypical handsome young child. I was searching for someone a bit more charismatic and strange-looking, because Harry is sort of caught between two worlds.

That uniqueness really comes through in the portrait of Harry from The Philosopher’s Stone. How similar does the model look to that sketch?

You never find a model that exactly matches the descriptions of characters in the books, so you always have to change them slightly. For Ron, I had to make his face and nose longer. There are actually not many changes for Harry, but I did make his eyes smaller. Often if you represent things precisely, it just doesn’t read right.

Harry is by far the most difficult character to draw, frustratingly. Partly because of the glasses, which tend to cut through his eyes at certain angles and rob him of expression. Children are the hardest thing to draw. You put a line out of place and you’ve aged a child by about ten years. In that portrait, Harry looks quite vulnerable, whereas now that he’s older I’m hoping to give him more purpose and a stronger stare because he’s been through a bit more.

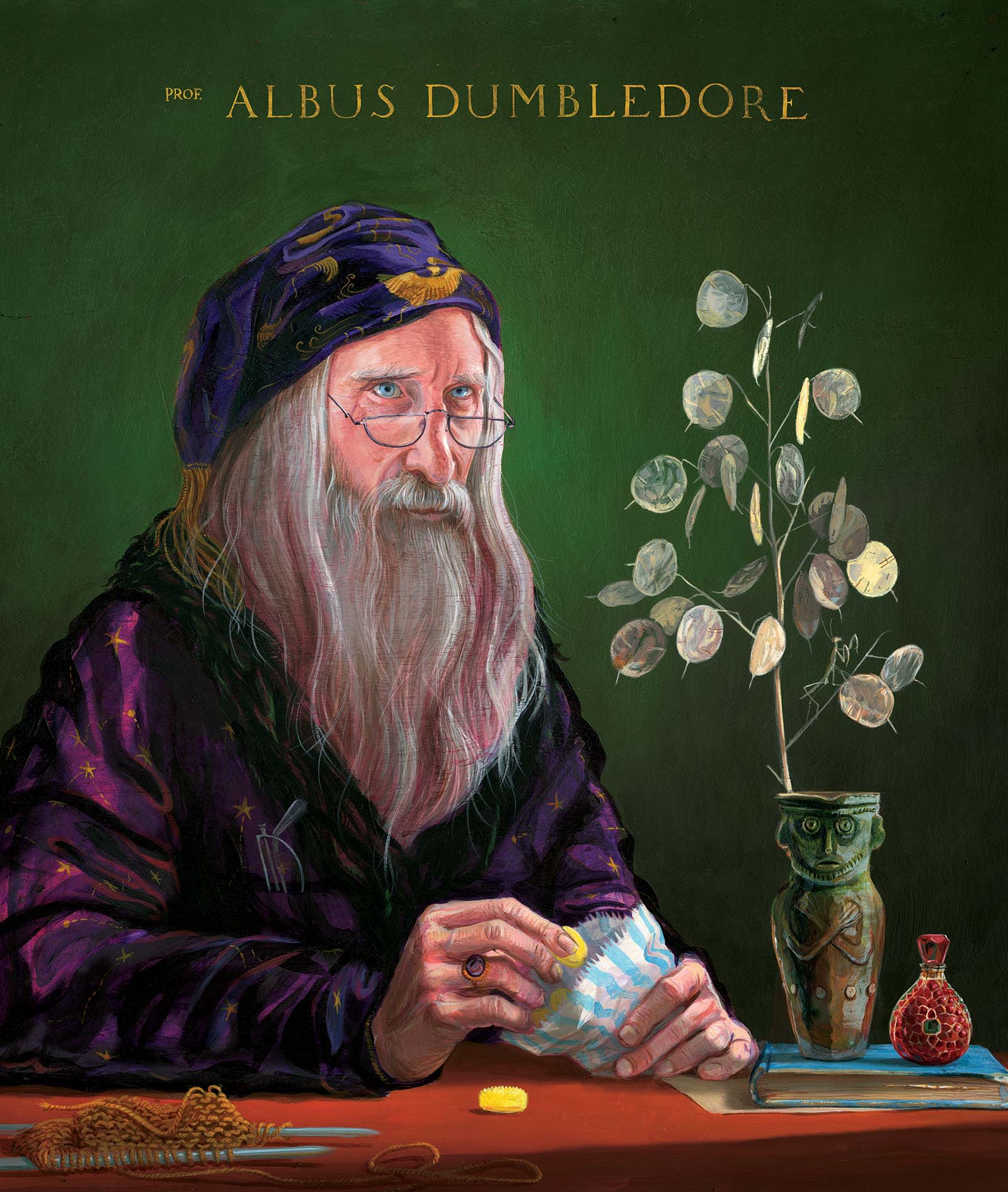

Dumbledore is one of the richest and most complex characters in the series. What do you see in the headmaster that you try to put into your drawings of him?

I haven’t shown Dumbledore much, which is frustrating because the gentleman I use as a model for him is wonderful. I’m looking forward to the later books, which have a lot more Dumbledore action. There’s a bit of symbolism in his portrait from The Philosopher’s Stone. The plant in the jar is called honesty in Britain because it’s transparent, but in Denmark it’s called The Coins of Judas, which is about dishonesty.

For me, there are two things going on with Dumbledore. I’m interested in his dynamic of being an extremely powerful wizard who has the possibility of doing dangerous things, but also this very humble, idiosyncratic, kindly old man figure. He has familiar echoes of stories like The Silver Sword, and there’s a bit of Gandalf and Merlin in him. Dumbledore is both familiar and difficult to read, and that’s why I like him. He sits perfectly in the Potter world.

I’d often go into nineteen-hour days, and it got to the point where I was so tired that I’d start to hallucinate.

How has it been working on The Prisoner of Azkaban?

If I’m honest, it’s been the most stressful experience of my life. I have to pretend that I’m doing something other than Harry Potter, because otherwise I start thinking about the responsibility and pressure of it.

When I first started the series, I didn’t sleep properly for about six months. I usually worked at least twelve hours a day, seven days a week, about three hundred and sixty-three days in a row. I’d often go into nineteen-hour days, and it got to the point where I was so tired that I’d start to hallucinate.

After book one, I had four days off and then we went straight into book two. During book three, I was an absolute wreck. It’s been self-imposed stress, I must say. No one was giving me any pressure, I just really struggled with getting it right. I can’t imagine what Jo [aka J.K. Rowling] must have gone through, because I experienced a tiny fraction of what she did. And I do love it. The minute I finish one book, I can’t wait to start the next one, even after it’s nearly killed me. I can’t explain it.

The reality of illustration is that you’re constantly trying to reconcile what you want to achieve with what you can achieve in the time you’re given. Only about fifty percent of what I design for each book ends up going in. I’m actually not showing Ginny Weasley until book four, which I’m sure I’ll be castigated for again when book three comes out.

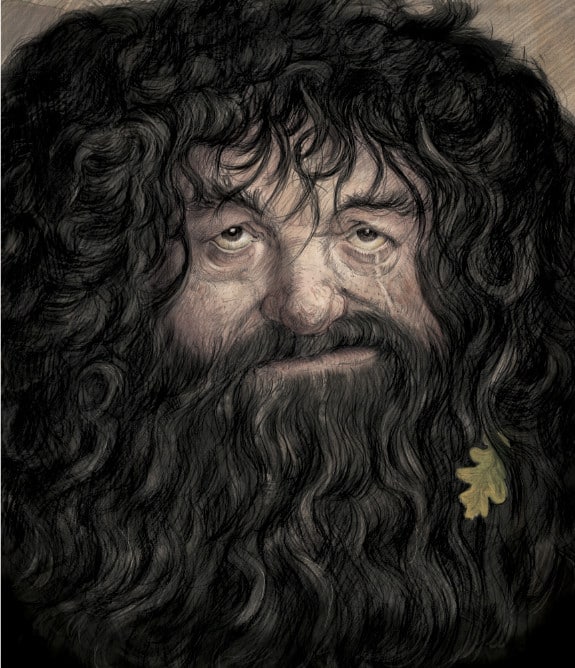

Lupin is only covered briefly in book three, but he’s a really great, tricky character. There’s a sort of sadness in him that hopefully comes across in his portrait. Sirius is more rock ‘n’ roll, edgy, and dangerous. He’s an outsider, partly because of his character, but also because he spends so much time as an animal to stay hidden. I used to own a very large dog, and I just love drawing dogs, full stop, so that’s been handy. It’s people that are difficult to draw.

What was it like having the Harry Potter film characters so firmly embedded in your audience’s collective consciousness?

It was very difficult. You really have to put your stamp on the work and say, “This is different from the films; this is different from what you’ve seen before.” When people first read the books they instantly have this very personal idea of what the characters look like, and for lots of people that’s been supplanted by the films’ cast. When my agent said, ‘Would you want to illustrate all of Harry Potter?’ I thought, ‘Why would I do that?’ The films were so successful and visually beautiful, and are so firmly entrenched in people’s minds. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to try and compete with that.

But then there’s a part of me that’s a complete control freak, and would love the opportunity to design everything in a world from scratch, which you can do with Potter. You get to reimagine the architecture, the landscapes, the people, the objects, the way magic is portrayed. In terms of an opportunity for an illustrator, I couldn’t ask for better.

There’s a part of me that’s a complete control freak, and would love the opportunity to design everything in a world from scratch.

How do you balance creating your own interpretation with accurately representing J.K. Rowling’s vision?

Jo has been great because she let me put things in that she hasn’t created. You always have to be careful you don’t step on the author’s toes. I try to do what I think is in keeping with the Potter world, but I also get to feel like it’s part of me. I’m just lucky that the author has never said, ‘Not this.’ There are lots of things in the illustrations that are very personal to me, particularly Diagon Alley, which has references to books I read as a child and television programs from my infancy, like Mr. Benn, which is very popular in the UK, and Bagpuss, which probably no one’s heard of in North America.

What is the process like for finishing an illustration? When do you know you’re ‘done’?

Some illustrators, like Alexis Deacon, seem to get it right straight away. I’m not one of those. So it’s a really frustrating process where I just have to do it again and again and again. No illustrator ever says, ‘Well, this is finished.’ We say, ‘I’ve run out of time.’ You’re never really happy with your work, because you always spot faults in it. At the moment, I look back at The Philosopher’s Stone and there are so many things that I think, ‘I wish I could change that.’ It’s only now, two or three years later, that I look back on books like A Monster Calls and think, ‘That was okay in the end.’

It’s interesting that you feel more satisfied with your work over time. Do you ever try to keep that in mind and go easier on yourself while you’re working?

You beat yourself up over it all the time. But you have to remember that while there are days when you get very down about your work because it never comes out the way you expect, at least you’re getting the opportunity to do it. Particularly in the current climate here in the UK, you have to remember that we’re extremely lucky, because it’s a real privilege to do art for a living.

I left university in 1997 and I finally had just enough to scrape by as a full-time illustrator in 2010. Right up until then, I was doing every job possible—working in hospitals, shops, factories, anything. But that informs your work, and makes you realize how valuable it is when you get there. There just aren’t that many illustration jobs out there. I know lots of people who are far more gifted draughtsmen than myself, and it’s just a case of some people getting opportunities and others not.

Can you elaborate on “the current climate here in the UK”?

I found Brexit very disappointing and bizarre. Not only will this make it harder for people to travel, but it will also be harder to work with foreign friends. I go to book fairs in places like Frankfurt and Bologna, and I love the fact that we are all European and have this shared love of books, telling tales, and imagination, despite speaking different languages.

There’s a lot of uncertainty and doubt about what’s going to happen between Britain and the EU in the future, and doubt is often enough to stop people funding projects, taking risks, and being adventurous. I’m grateful to Bloomsbury for taking a risk on someone like me, who wasn’t a particularly well-known illustrator, to take on a project like this.

Particularly in the current climate here in the UK, you have to remember that we’re extremely lucky, because it’s a real privilege to do art for a living.

Were you in the studio today?

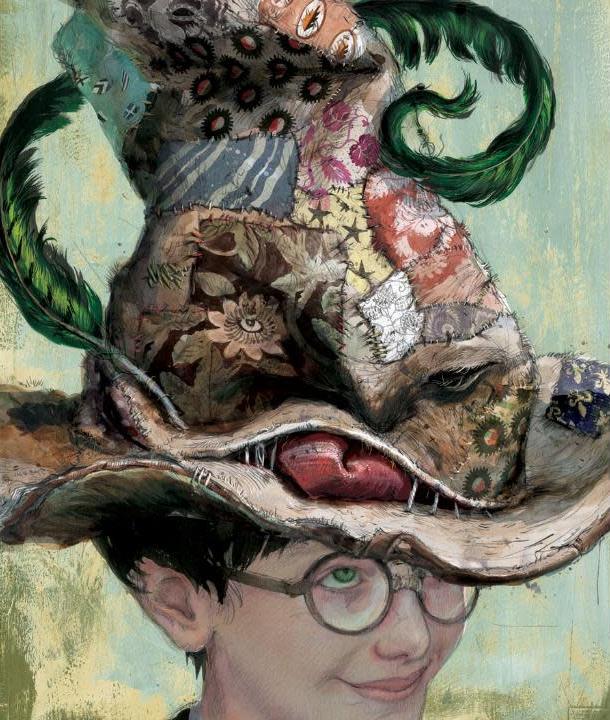

I’m now on a break between books three and four, which has been fantastic because I can really enjoy the process again. Today, I was struggling with designing Mad-Eye Moody’s face. There’s actually more physical description of him in the book than of other characters—a heavily scarred face, one large eye, and one small eye that’s been replaced. But I have to figure out how frightening he can be. In book one, I originally drew Voldemort’s full face with a shark-like mouth and layers of tiny teeth. But it was deemed too frightening for a children’s book, and I ended up covering him up with a scarf. So I’m quite conscious of not being too frightening.

As the readership gets older and the stories get darker and more adult-themed, I think the drawings will feel more mature. As Jo has said throughout the whole series, the story’s overriding theme is death, and what it means to the people that live. I don’t really think of what I do as illustrating for children because I tend to illustrate for myself. You end up thinking, ‘What would I like to see in a book?’ I’d consider myself more of a young adult book illustrator, so hopefully the books will get easier for me as we go along.

What does J.K. Rowling think of your vision of her world?

She wrote me a lovely letter saying that she really liked it. It was a wonderful day when it arrived. I was working so intensely at that time that I forgot the books are in the shops and people actually see what I’m creating. And then I got this letter saying that she liked what I was doing, and it made a huge difference. It made all the long nights and difficult times worthwhile. Ultimately, I’m trying to please the author. I can’t read her thoughts, but I really try to do something that agrees with what she was thinking.

Have you met her?

No! I can talk in big groups of people, but I’m not very good at meeting people one-to-one. She’s suggested we should meet. I’ll be honest, I was kind of hanging on to see how the books did. If I managed to kill the most successful children’s book series in history with terrible sales, I thought it’s probably best we don’t meet. But luckily it’s sold well. I’d love to meet her. Maybe one day.