I went to Frieze Art Fair with an open mind and notebook in hand. When I found artwork that moved me, or gave me a memorable reaction, I wrote down the names and details. Later, at home, I was surprised to discover that almost all of the artists scribbled in my notebook were women. It was entirely unintentional.

Except for Eva LeWitt most of the artists on this list are definitely not emerging talent. They are, however, “under the radar” for most art lovers. Judith Linhares, for example, is well-known and respected in New York, but has yet to receive the international acclaim she deserves. Irma Blank, a senior European artist who was integral to the development of esoteric conceptual art, is only now breaking out of an insular career in Italy. Kiki Kogelnik’s work at Simone Subal Gallery took over their Frieze booth with psychedelic paintings and drawings made in the 1960. Her work could easily fit into any of today’s downtown painting shows. Plus, Jessica Dickinson’s laborious paintings and drawings are finally getting the attention they deserve. It was thrilling to see Dickinson represented by two galleries at the fair.

Frieze New York takes place every May in Randall’s Island Park just across Manhattan’s East River. It “brings together the world’s leading modern and contemporary art galleries, innovative curated sections, a celebrated series of talks, site-specific artist commissions and the city’s most talked about restaurants.” Although I’m not normally a fan of art fairs, this one has always proved to be worth the trip.

Here are the woman artists who stole the show this year at Frieze with subtle, mature and thoughtful work.

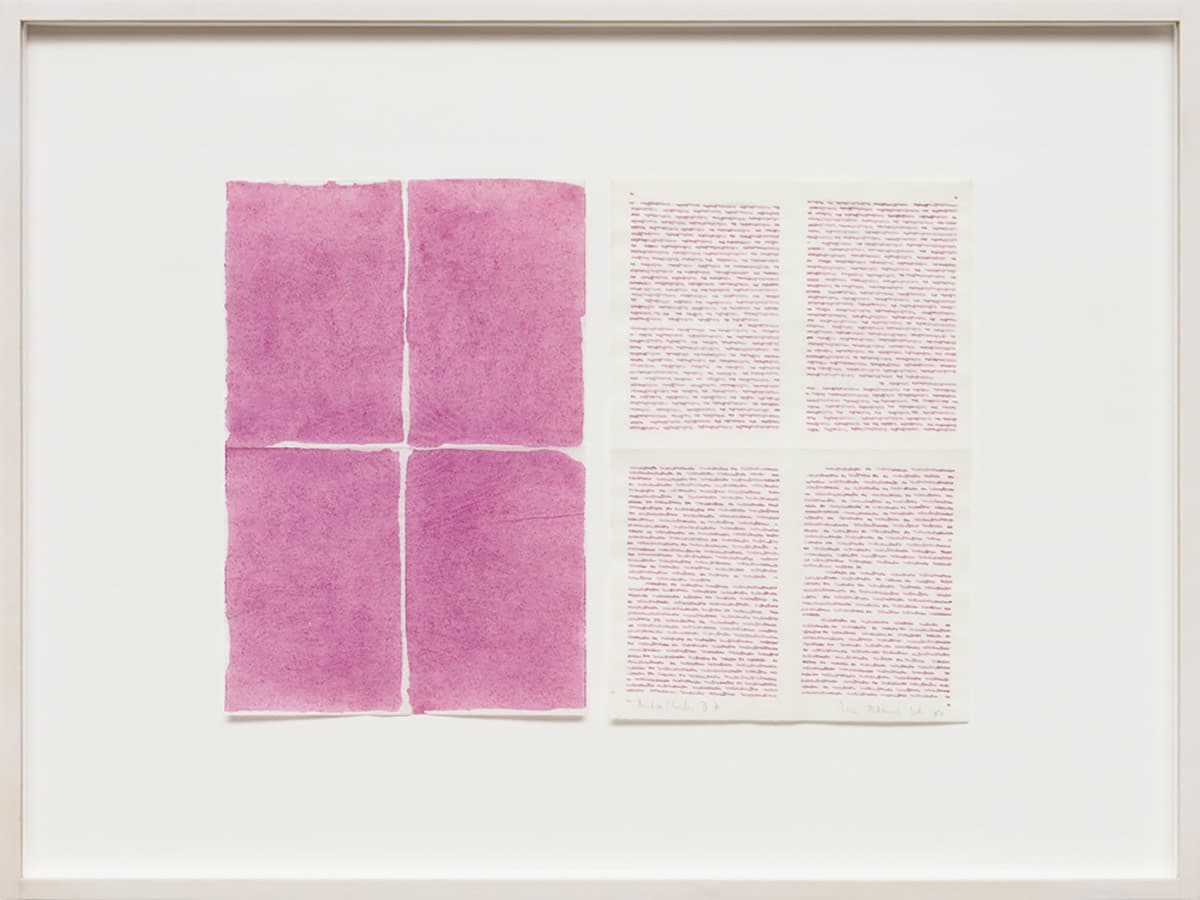

Irma Blank

Irma Blank is a German-born artist who lives and works in Italy. She was a formative part of the esoteric conceptual art movement in Europe. She has exhibited regularly in Europe for over 65 years and has only recently gotten international recognition for her work.

It was a thrill to see her subtle writing-based works displayed in a spotlight booth at Frieze. Although the artist’s work migrated in later years to bolder monochromatic large-scale paintings, this smaller series called “Radical Writing” was pursued solely over ten years. For the work pictured above, she recreates the action of writing, without the literal content. Each “word” written corresponds with a breath.

In a method like meditative walking, she enacts meditative writing, to separate the work from her own subjectivity. A pursuit that may or may not be impossible. Her work recalls other dedicated sage artists such as Agnes Martin. Blanks’s work is consistent, provocative, and repetitious. Her ethic produces series that are hauntingly beautiful and puzzling.

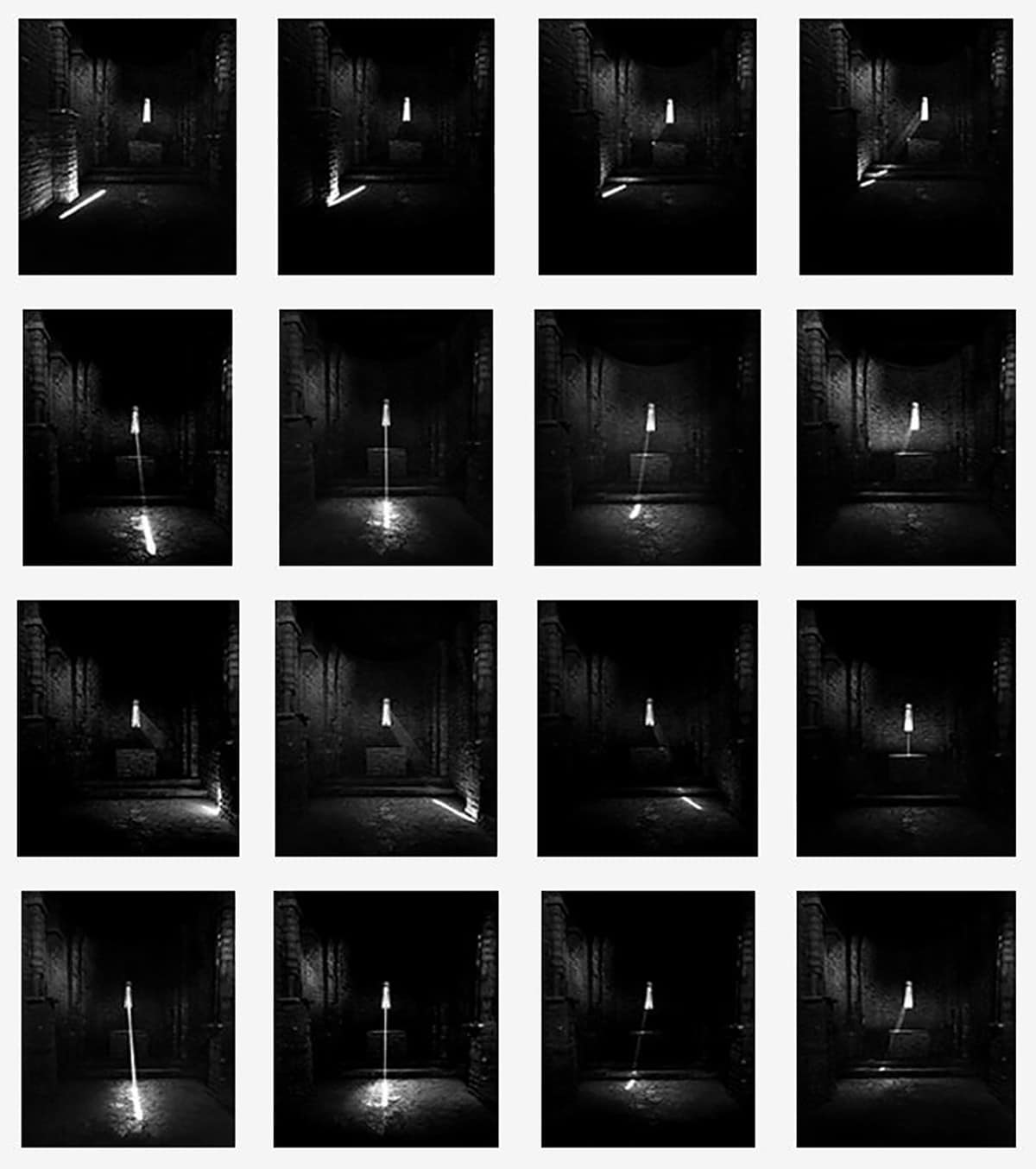

Ursula Schulz-Dornberg

Gallerie Luisotti featured Ursula Schilz-Dornberg’s work at Frieze. I was first enraptured by the series of black and white photographs of strange architectural bus shelters around Armenia. The gelatin silver prints captured these alien no-places as either empty or housing despondent people waiting.

Sixteen black and white photographs were installed in a grid on the wall, each depicting a slitted chapel window with light pouring into the darkened interior space. The images were taken at different times, indicated by the changing angle of light. This simple strategy for showing how light affects place, and represents time, was magical.

Joanne Greenbaum

Opinions about Joanne Greenbaum’s uninhibited colorful abstractions can be polarizing. Her work employs multiple ways of making a painting, or drawing. She’ll pick up a paintbrush, pour paint, flip the canvas, draw with markers or any other colorful pen or mark-making tool. This flexible attitude toward image making and materials is difficult for some to swallow. Why does she do that? What is it all about? Her refusal to answer, and impetus to simply make, is precisely what I find interesting. We don’t always need to question validity—the playfulness of Greenbaum’s work isn’t meant to be criticized, but simply enjoyed.

Eva LeWitt

I wrote down Eva LeWitt’s name before I knew that she was in fact Sol Lewitt’s daughter. Being the offspring of such a revered artist can’t be easy, but the work exhibited by VI, VII at Frieze, where “exciting new talents” are exhibited, stands on its own.

I should mention that looking back upon LeWitt’s early press coverage, it’s clear that this new work displayed may be a large leap forward. Some of LeWitt’s earlier work, understandably due to her age, appeared juvenile and a little obvious. These new pieces use rubber, clear and colored vinyl cut in the same proportions at vinyl siding, acetate, foam and stuffed fabric.

The materials don’t harken back to a machismo presented by minimalist forefathers like the notorious Richard Serra. Instead they utilize flexible, common and synthetic materials. Their flexibility and limp attitude seem to point to the personification of objects and their potential fallacy. The human quality to these large scale object installations is their most captivating quality.

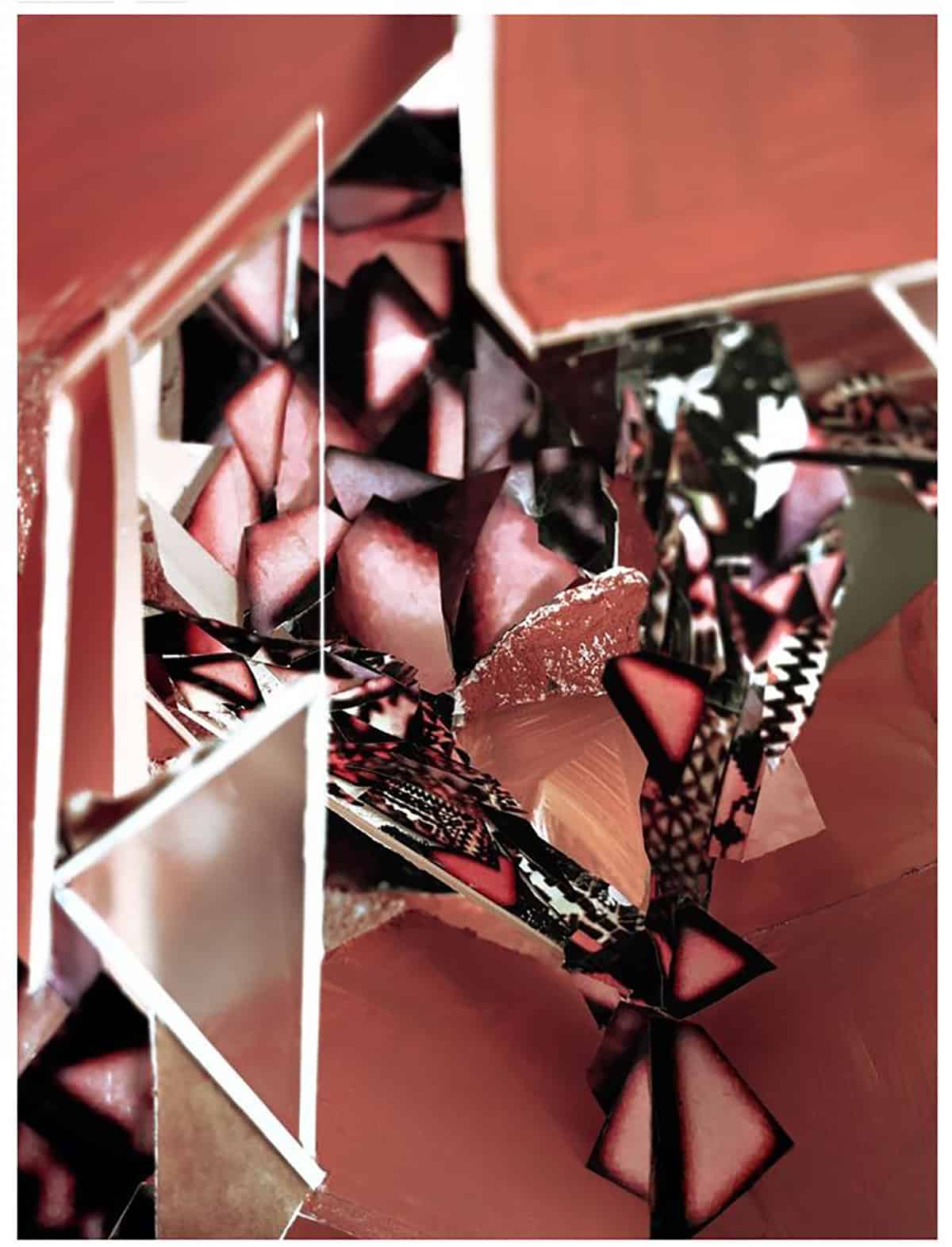

Yamini Nayar

It’s surprising that I’m seeing Yamini Nayar for the first time exhibited by Mumbai’s Jhaveri Contemporary at Frieze, considering the fact that she’s American and based in Brooklyn. Nayar compresses different media and attitudes into a simple photographic gesture. She uses collage, refuse, sculptural material, and paint to create tableau that then are photographed as their final iteration.

The results are dizzying, scaleless, and dense. The concluding photographs of layered and rich multifarious object situation becomes impossible to pare down or piece apart. The images then become circular in nature as the viewer can’t discern a beginning or an end. The work’s indecipherable quality is attributed to the homogenous effect of photography. It’s photography’s edgeless-ness that Nayar is elegantly, and maybe frustratingly, profiting from.

Judith Linhares

Judith Linhares was the one booth I was specifically looking for at Frieze. Her work might look a little bit like Dana Schutz’s work, a much younger artist who has been the subject of hot debate recently. But, as my painter friends exclaim, as if referring to a 90s hip hop idol, Linhares is the original gangster.

Her work is full of personal and kitschy imagery. It pervades camp, and garishness, but in a way that creates a familiar draw into language and story. The bright, almost sickly sweet colors are applied in impasto large brushed on strokes. The images of cats, birds, and women holding up their dresses to reveal their underwear (a metaphor for all painting maybe?) almost appear to glow from their multicolored surfaces. They dance and become real just through their insistence of marvellous paint handling. Her work exists somewhere between her roots in L.A.’s circus of entertainers, and story book memory.

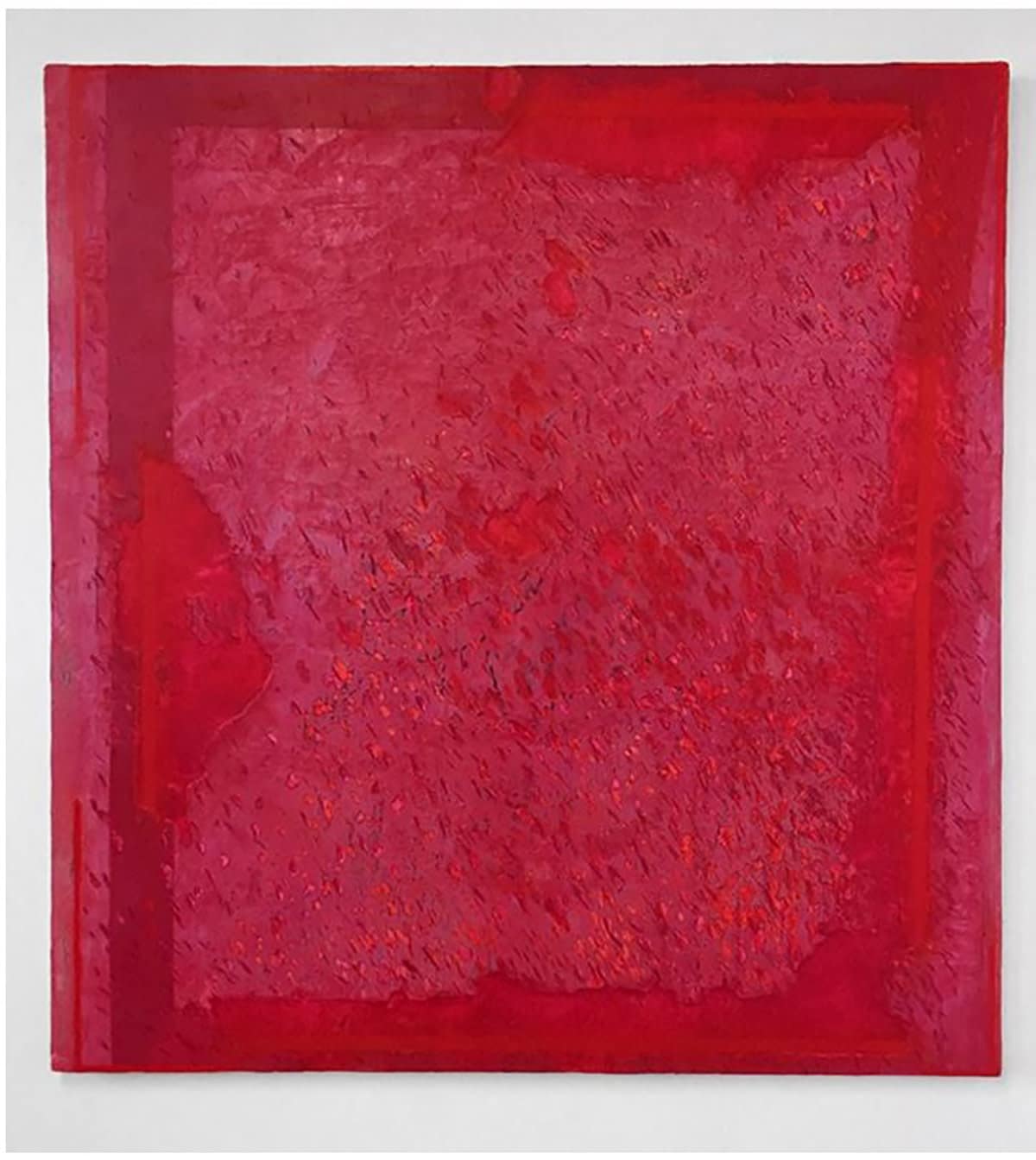

Jessica Dickenson

Jessica Dickenson’s painting process is all about time. She layers paint as if its primordial mud upon a heavy limestone polymer and plywood surface. The process means that it takes about a year to complete a single painting. She layers, and scrapes paint from the surface, over and over, until the piece begins to make itself. The paintings have a vitality onto their own. Their long working time and relationship to the hands of the artist complicates their position. Their surface resembles worn skin. Its indexical marks, relate to their strange transformative temporality of their making.

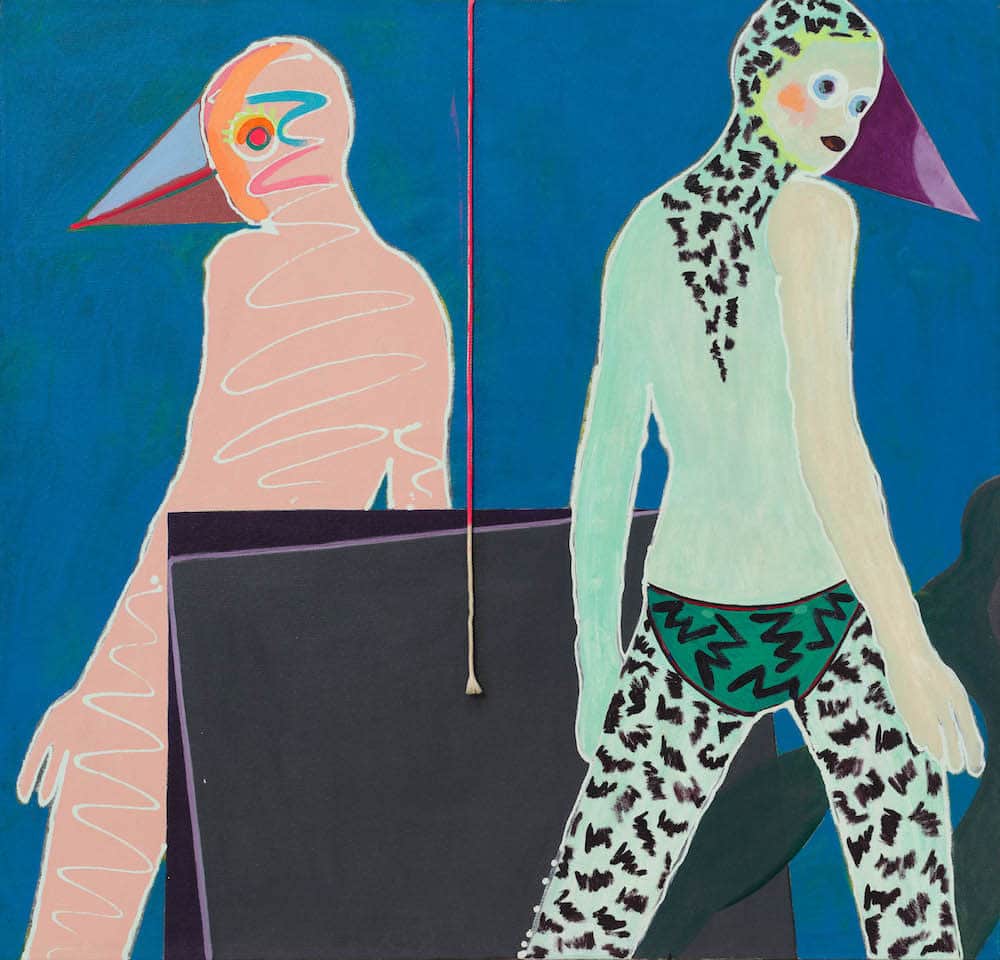

Kiki Kogelnik

Kiki Kogelnik’s work hit me like a tab of acid. It’s burning color, spinning patterns, and transforming bodies energized me in a pop explosion. The work reveals a futuristic spirit and exploration. What’s most impressive is that this work was created in the 1960s and 70s, way before the frequent discussions about androgynous bodies or cyborgs that are popular today.

Having a similar feeling to the movie Blade Runner, Kogelnik tries to imagine a future body without enough information. This lack of exactitude only provides more play, and more fictitious flare. At first the paintings seemed to function exclusively like pop icons rather than an investigation into the logic of a painted surface. However, the paintings slowly revealed more sophisticated details, like small sculptural elements, and an interesting play between thin paint and bold colored surface.

These paintings feel like somehow Kiki Kogelnik could look into the future, like they’re made by a young painter in Bushwick today—especially with their neon color schemes and prominent figurative elements. Like Hilma Af Klimt who created abstract works far before her time, Kogelnik was a spectre into a future painting discussion.