What is the “American Dream”? That was the starting point for Ian Brown’s New York Times acclaimed photography series titled, appropriately, American Dream.

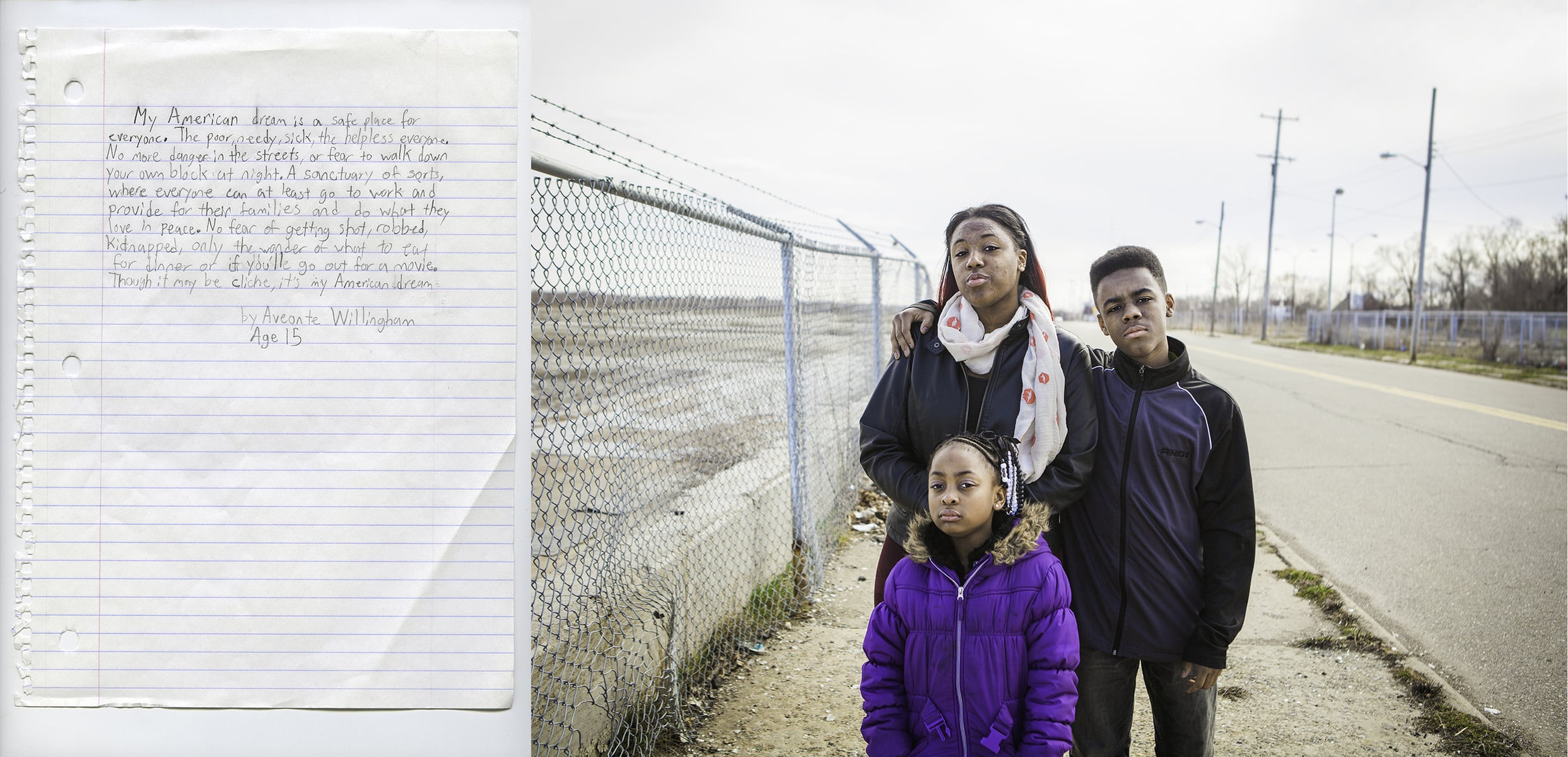

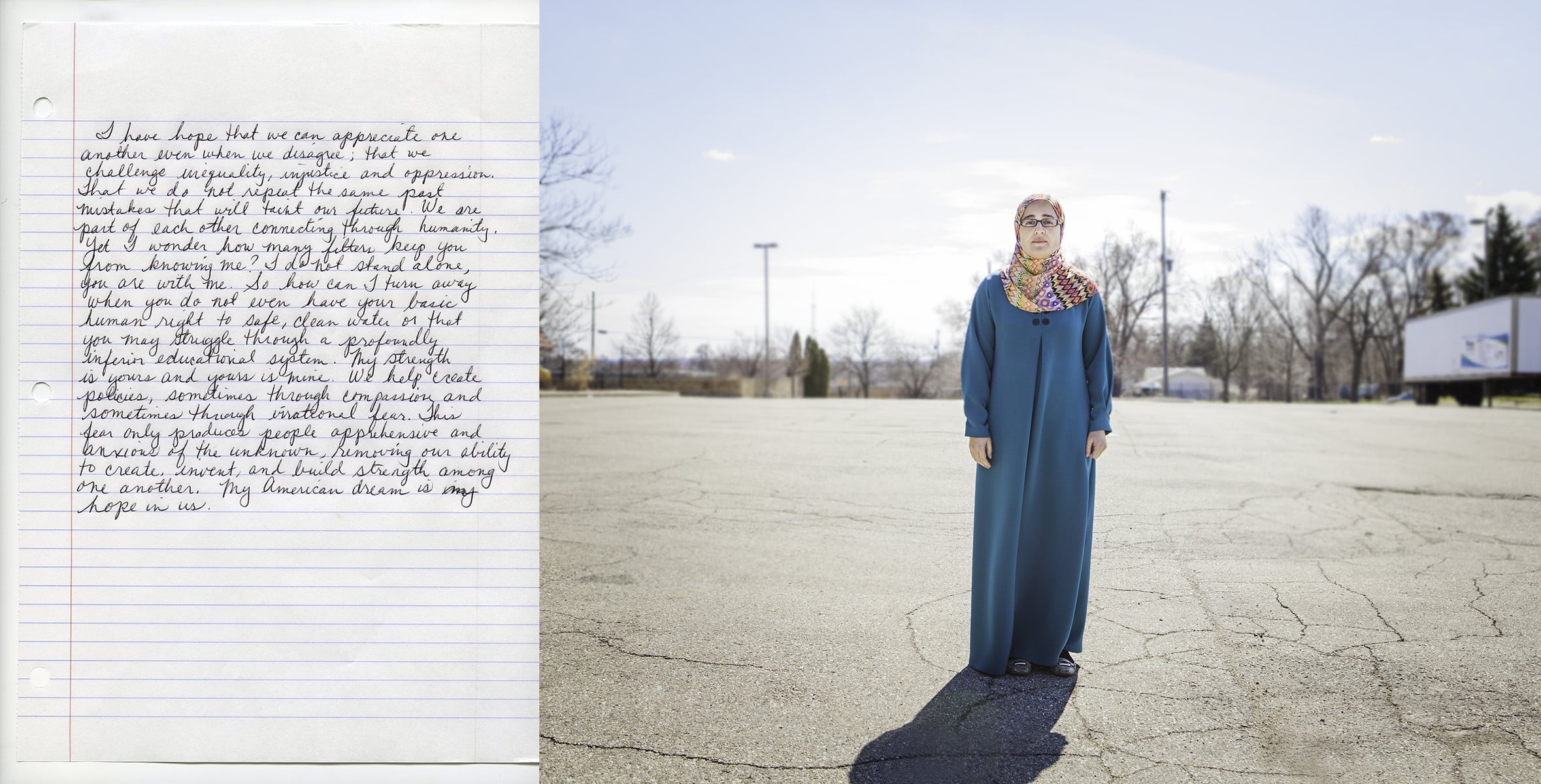

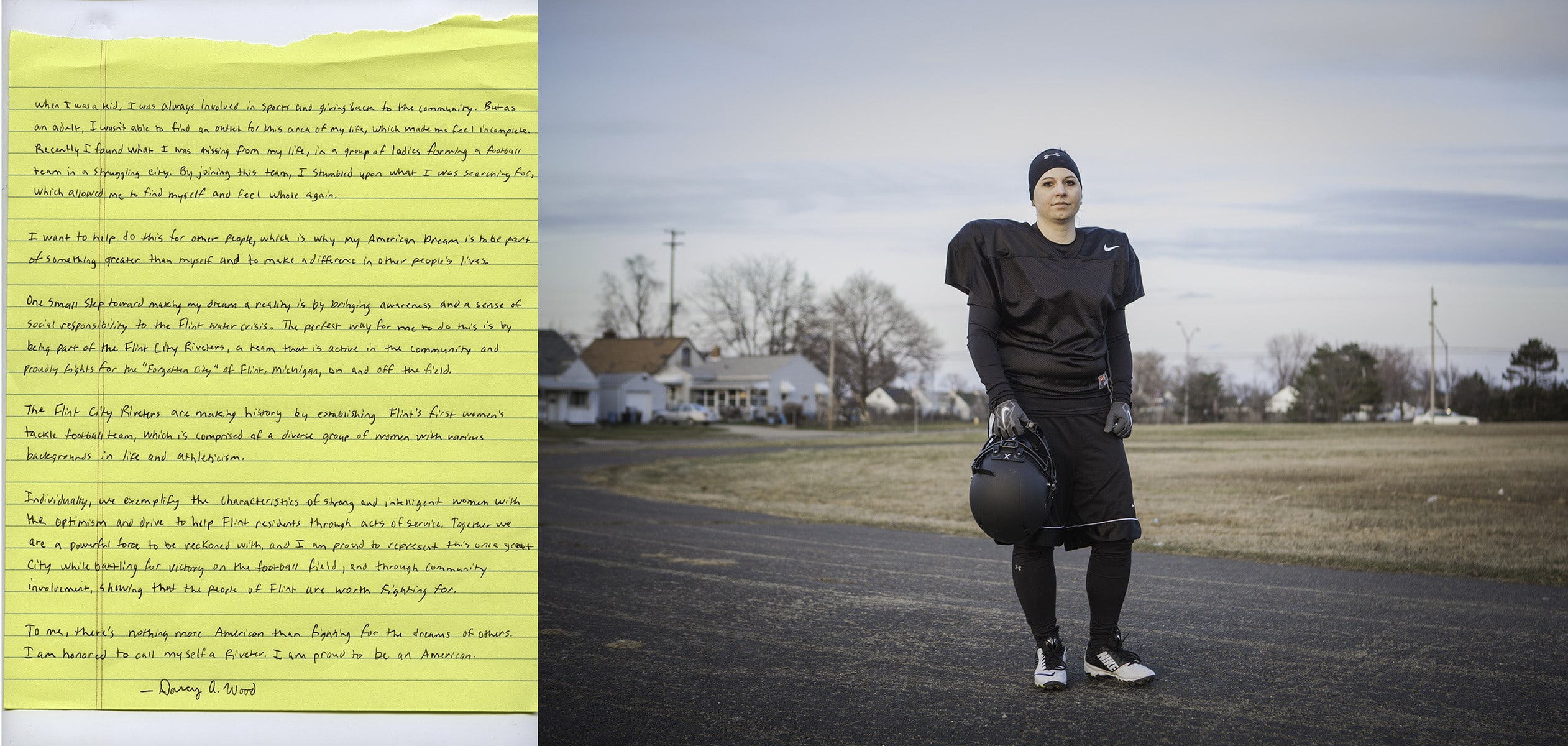

In 2007, the Canadian photographer began travelling around the United States and taking portraits. He asked each person for their definition of the “American Dream” and got them to write it down on a piece of a paper. The result is a project that magnifies portrait photography by pairing it with their own handwriting.

It’s unsurprising that the New York Times picked up Brown’s photography series for an online interactive feature. There’s an intimacy to Brown’s work—it tells a classic story in a new way. For many photojournalists, getting published in the New York Times is the ultimate goal. We called up Brown to find outs the do’s and don’ts of pitching your work to art directors.

This is what he told us:

I’ve been a photographer for 18 years, which is crazy. When I was young, there was an art director who had a huge impact on me. I put together a portfolio based on the kind of work that I thought she liked, and she sent it back to me with a note that said, “When you learn to do something original, send me some more work.”

The next day, she emailed me and said, “Listen dude, I don’t mean to crush your dreams but my point is, don’t send me the crap that you think I want to see. Send me what you really like to do and what you think you can do better than other people.”

So I did. I put another portfolio together and sent it to her. You know what? She called me immediately and said, “Okay, now we’re talking. I know that you like doing this because the work is way stronger. Don’t ever send things that you think you should just because everyone else is doing it or that’s what the trend is. Shoot what you really love to do and eventually people will find you.”

There are billions of photos uploaded every day now. If you want to pitch to the New York Times, it boils down to trusting in your work and getting it into the hands of people who can make decisions. If they like it, they’re going to want it. If they see potential in it, but it’s not quite where they think it should be, they’ll probably get back to you and tell you what you can improve on.

In my experience, all the top art directors are really supportive people. They love photography, right? And they don’t want to say just “no”. They can see the potential and they try to encourage people to either keep going or change something.

Getting critical feedback is important. I think it’s important to detach ourselves from our work sometimes. Photographers can confuse the experience of taking the photo with the photo on its own.

For example, in my American Dreams project, I’ve photographed a couple of hundred people and I have an experience with all those people—driving to their house, hanging out with them, having dinner on their porch and meeting their kids. It ends up being a really personal experience and there’s this connection, a bond. I drive away and think, “Wow that was amazing meeting those people.”

But then, when I look at the photographs, I have to look at it from an impartial standpoint and think, “Well, is it a good photo and does it work, or am I really looking at this because I had a great time with those people and therefore that makes me think it’s a good picture?”

See more of Ian Brown’s photography at his portfolio, built using Format.

Want to read more about getting published?

How to get published in Lucky Peach

How to get published in National Geographic