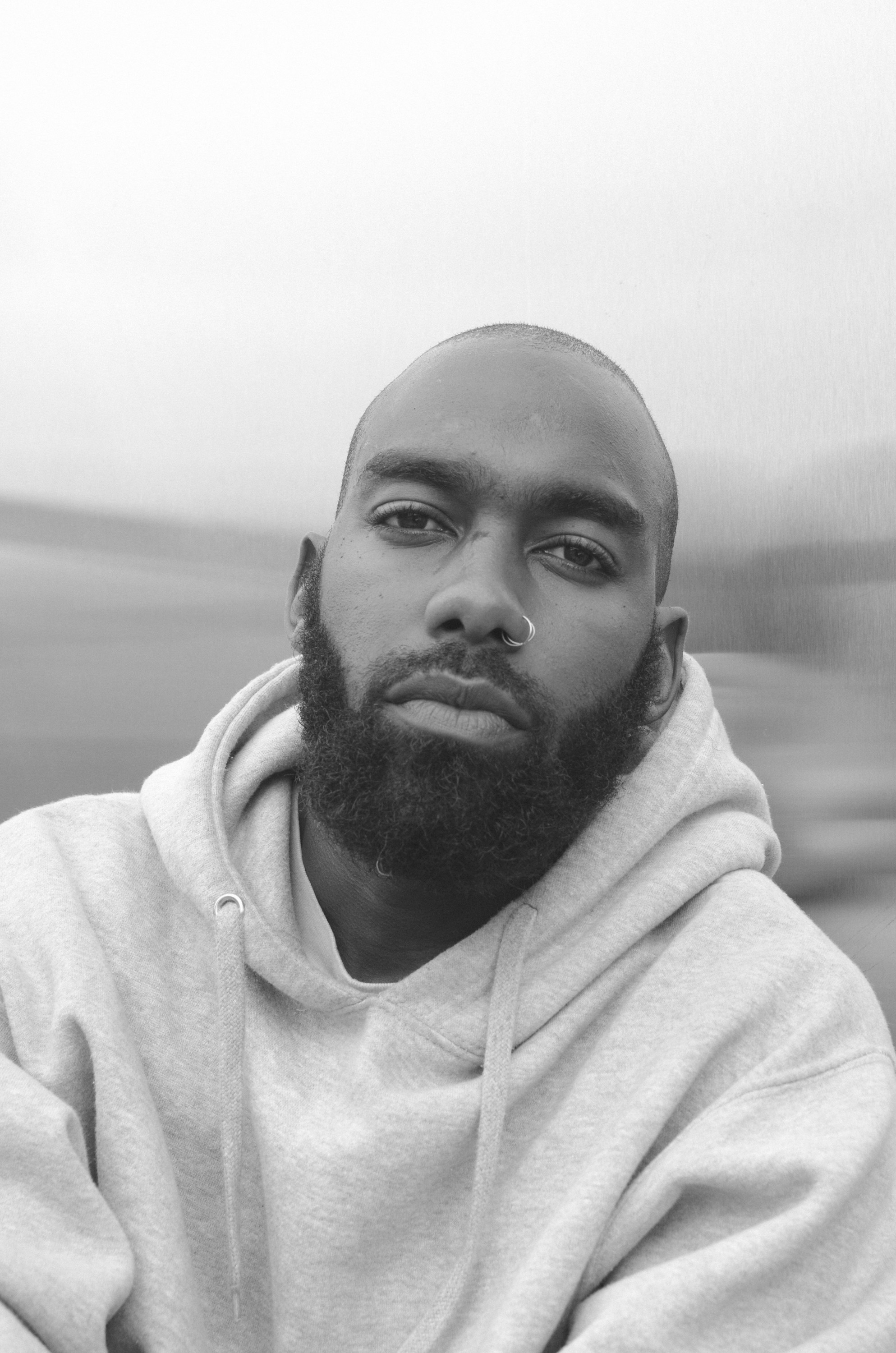

Photographer Yannick Anton’s latest series reclaims the printed family portrait. “A lot of the time, people just have images on their phones and not on their walls,” he explains. “Looking back through history, the idea of the family photograph starts with rich, white, and wealthy families being able to document their history. If people of color were in front of the camera, it was a scientific or fetishized gaze. This project fills the void of not seeing ourselves—people of color, LGBTQ and all families regardless of income.”

Titled Limited edition, Anton found subjects by inviting couples and groups to a pop-up studio at Toronto’s Gallery 187. The resulting images are a celebration of the importance of family, and the friendships that become chosen family. As you can see from his portfolio, Anton uses his camera as a tool to connect with his subjects. The ease and intimacy he captures should be studied by anyone interested in portrait photography.

Anton has been a professional photographer for eight years, and gained most of his experience documenting a long-running monthly party called Yes Yes Y’all. “Looking back it was where I learned how to shoot and interact with people to get the most honest portraits,” he told The Fader, who published his event photos in “Inside Yes Yes Y’all, Toronto’s Most Poppin’ Queer Bashment.”

We caught up with Anton to find out more about his interest in family portraits, why he uses instant film, and photography’s role in creating a space for diversity.

I’m not making work for the internet, I’ve never been doing it for the internet, all my photos are for later, for when we look back at history.

Format: How did you start photographing?

Yannick Anton: My best friends Keita Juma and Brendan Philip are musicians, and for a while, I was the only one at every one of their shows all the time. That’s how I started photographing—simply because I was the one at every show and they needed images. Sometimes people would come through and sometimes people wouldn’t come at all, but I still had to find a way to make it look packed and hype. Then it got packed and hype and I had to figure out how to make good images in such a crowded space. They played a show for Toronto Pride called Yes Yes Y’all and I’ve been photographing that event for seven years.

What was your experience with formal photography training?

I’m not good at school. I applied to go to university but I didn’t get in, so I was like, ‘Fuck that, I’ll just figure this out by myself’. I learned by asking people who knew more than me. I was part of a youth photography residency program that taught lighting and structuring a conceptual project. Che Kothari was a photographer who helped me out a lot and let me use his equipment.

That residency experience made me realize that I want to exhibit my work in galleries. I’m not making work for the internet, I’ve never been doing it for the internet, all my photos are for later, for when we look back at history.

I feel more like a historian than a photographer, especially with the family portraits. I want to take pictures of people and families once a year and then eventually exhibit the images in a building where you could walk into rooms of people’s lives, so people can see how they’ve grown.

I’ve been shooting the same party for seven years, I’ve seen the same people in different stages of their lives—some have died. I’ve watched myself grow as a photographer. When I started out I didn’t even own a camera. I had to borrow a camera every month and now I own two cameras. Things change and it is in its own progression that I find importance.

What sparked your interest in family portraits?

My grandmother used to go to Sears to take family photographs and give them as gifts to the family at Christmas, and then one year she stopped going. I never had the opportunity to go with her, so I don’t have any proper family portraits.

Is your grandma alive? What does she think of the series?

Yeah, she’s alive—my whole family is like, ‘Ah, that’s nice.’ I guess they’re happy to see me do something for so long because I was one of those yutes that no one knew what the fuck I was going to do with my life. I didn’t like school, I didn’t like jobs, I didn’t like listening to people. My family is my hardest critic for sure. They’re always like, ‘I’m never going to see that photo, so don’t take the picture.’ I have to print out a book one day to be like, okay—here are all the pictures!

Where you into family albums when you were younger?

Yeah! I used to spend hours and hours in the basement just going through family photographs and also album covers. My mother used to have so many records down there, it was a definite escape for me, simply because I didn’t get along with everyone I grew up with. Give me crayons and leave me alone down there and I’d be good.

Take us back to the basement—is there anything that you remember that stuck with you?

In those photographs, everyone was super fucking happy. The 60s and the 70s were a great time for fashion. I think the feelings in those pictures are still unmatched. That style and aesthetic was who they were, and I really appreciated that happiness. They didn’t care if those pictures were blurry or if body parts were cropped off—it was all for the moment.

Did you do any research in preparation for Limited edition?

No, I don’t really research. I used to look at other photographers a lot, but now it’s just annoying. With Instagram, it feels overflooded. It starts to feel like a comparison between successes. I’m on my own shit, I’m not super famous, nobody is really putting me on. I don’t have a Fuji sponsorship, a Canon sponsorship or a Lomography sponsorship. Those are all the ones I want, but I don’t have them so I’m just out here doing this on my own and with people who are also just figuring this out. I would love to take a company’s money, film is really fucking expensive, cameras are expensive!

What did you shoot the family portraits on?

A Canon 5D Mark III and a Lomography instant film camera. The instant film is important because I want people to have pictures on their wall, it’s important to be able to give people a physical object to take home instead of just an email attachment. Knowing that people take these photos, and put them up on their wall, means way more to me than 1,000 likes on social media.

Was it important that people of color showed up at the pop-up studio?

A lot of people of color showed up, and that was just as important as seeing many queer people there as well. The concept of family has always been diverse, but what the white picket fence family is the only one shown: the mom, the dad, 2.5 kids, and a happy dog. I grew up with friends who had that, and I wasn’t hurt by seeing it, it just wasn’t my reality or the reality of so many others. I never wanted to pretend to be anything that I wasn’t.

That’s why this series is so important to me, it’s about documenting diversity beyond a nuclear family. I visually challenge the traditional family portraiture in the posturing of the family portraits. I look for true moments of personality that help further the idea that family is more than just one thing, that there is space for color and queerness. There is space to break that traditional imagery and demonstrate honest love and connection.

Find more of Yannick Anton’s work on his portfolio, built using Format.

Portrait photo by Patricia Ellah