I spent two months at an artist residency on the island of Saint-Louis, Senegal. My primary objective was to photograph a country that had enthralled me since childhood. This turned out to be much more difficult than I expected, and the experience challenged by perceptions about photography in a life-changing way.

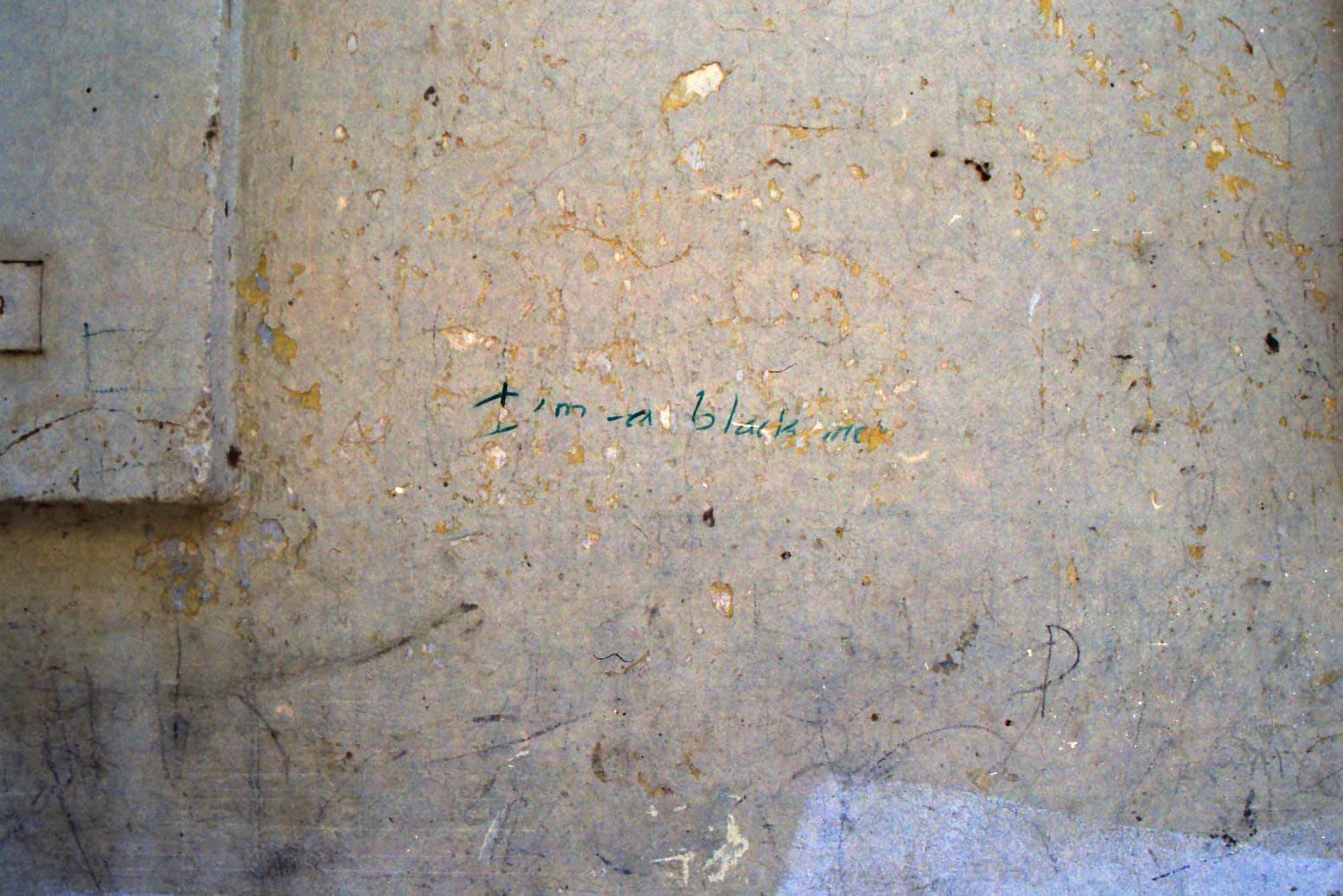

Saint-Louis is the second most populated city in Senegal, second to the country’s capital Dakar. It rests on the western coast of Africa, near the mouth of the Senegal River, the last stop before the Atlantic Ocean. The city itself is a feast of color, and a decay of heat and humidity. It’s a display of colonialism leisurely fading to reveal a suppressed and deeply rooted ancient African culture.

It’s full of people battling between what is old and what is new, between what has died and what is accumulating strength for life. A community in the midst of a metaphysical bond and a necessary unraveling from selective spaces and from various points of time. An island in transition clenching onto it’s traditions, but most profoundly a place beyond shit and desire.

In photographing Saint-Louis, I had overlooked the overwhelming contempt the Senegalese have for photographers. We can’t be trusted. Europeans can’t be trusted. And I can’t blame them. Over centuries, Europeans have solidified a bad reputation, to say the least. It was something I couldn’t argue with.

I remember the first frame I attempted to capture during my visit. I was on a bridge walking from Saint-Louis to Ndar Ndar and I pulled my point and shoot from my pocket. All around me I could hear, ‘“TOUBAB, DEETDEET!” which literally translates to “WHITE PERSON, NO!”

Suddenly warmed with shame, I tucked my camera back from where it came and what followed me was the collective sound of people omitting a tsk tsk slither under their breath—a man even waved his finger at me very disapprovingly.

I had wanted to photograph a fisherman’s boat on the river beneath the bridge, no one was on it, there was nothing sacred to it. I didn’t understand why I was being shamed. Being a photographer is being a voyeur, there’s a great deal of perversion to it. I look at my camera like a cloak: when I stand behind this object I’m completely transparent, but this is just the narration of my poetic imagination. I’m just as visible as my subject.

Being a photographer is being a voyeur, there’s a great deal of perversion to it.

The contempt for film and photography in this region stems from decades of false documentation. Few tourists visit the area aside from Westerners experiencing a quarter/midlife crisis on a crusade to West Africa to “help” those they perceive to be “unfortunate”. There’s also Spanish women indulging in the thriving male gigolo industry. The former are the main culprit for this false perception of that Senegal is a constructed lesser nation, that it’s a third world country.

Senegal is not better, not worse, just different. That’s it. There’s no use dwelling on poverty or pollution, it’s everywhere. I never understood why anyone would want to solely set their focus on a damaged landscape or a promised land when the beating pulse thrives on the middle ground. I always think of Tom Stoddart’s photograph of Meliha Varesanovic as the best war photograph ever taken; there’s no blood there’s no tears, only a woman’s pride. An honest fragment.

That was my goal, to collect fragmented images of singular details amongst chaotic surroundings. I wanted to create a fictional memory based on truths that were whispering secrets around me. Chris Marker once wrote, “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember, we rewrite memory much as history is rewritten. How can one remember thirst?”

I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining.

I “remember” shooting a frame of a pack of wild dogs coasting alongside the Atlantic shore, some vision of freedom. Moments after I took this photograph, the pack of dogs came running towards one of my girlfriends and surrounded her and then one bit through her calf muscle. She was bruised and bleeding, but so hell bent on swimming in the ocean that day that it took an hour for us to convince her to see a doctor.

In Senegal, one of my favorite acts of remembering is a shot I took of a coffin laying on the side of the road beside a silver Toyota. There was a pile of garbage on the left side of the coffin but I omitted that from my frame. Once photographed, a 16-year-old girl came out of her house and told me her neighbor had passed away of mysterious circumstances the previous night in her sleep. Members of the community were preparing the body for burial. She invited me into her home and we sat in her courtyard with her older sister, one of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen. The girl went to her bedroom, brought out a small pile of books and read me passages written by her favorite author. She told me stories of her boyfriend, whom she had kept secret from the rest of her family for three years now and a time earlier in the year when she was sent to the hospital to be treated for an illness she had fabricated only to get out of a school exam. It was intrinsically sweet. There was something unnamed, something so completely perfect about that moment, but the most vivid image I have of that afternoon is a coffin and a silver Toyota.

My photographic experience in Senegal was the reinforcement that photography is as much a false documentation of history as the written word, you can’t read outside the lines just as much as you can’t see outside the frame. You can imagine it, you can destroy and create worlds. You can layer one illusion outside another, but truth is always stranger or lesser than fiction.

Find more of Sonia D’Argenzio’s photography on her portfolio, built using Format.