A true designer knows that nothing beats attention to detail. In his art house horror film The Witch, writer-director and former designer Robert Eggers recreates the authentic world of 1630 New England to pull his audience deeper into the forest.

When make believe is at its most believable, you find yourself easily suspending disbelief. Although you know that you’re only watching a movie, the realism breaks down your defenses until you’re deeply invested in this story about an early Puritanical family terrorized by witchcraft.

The Witch (or sometimes written in Old English typography with two “v”‘s as The VVitch) is Eggers’ debut feature film and it’s become a blockbuster hit after winning the Directing Award at Sundance Film Festival last year. Somewhere between a folktale and a nightmare, The Witch tells the story of a religious man who is banished from his colonial plantation and moves his family to an isolated farm at the edge of wilderness. Things quickly get weird as a baby vanishes, a black goat acts up and the remaining children accuse each other of satanic possession.

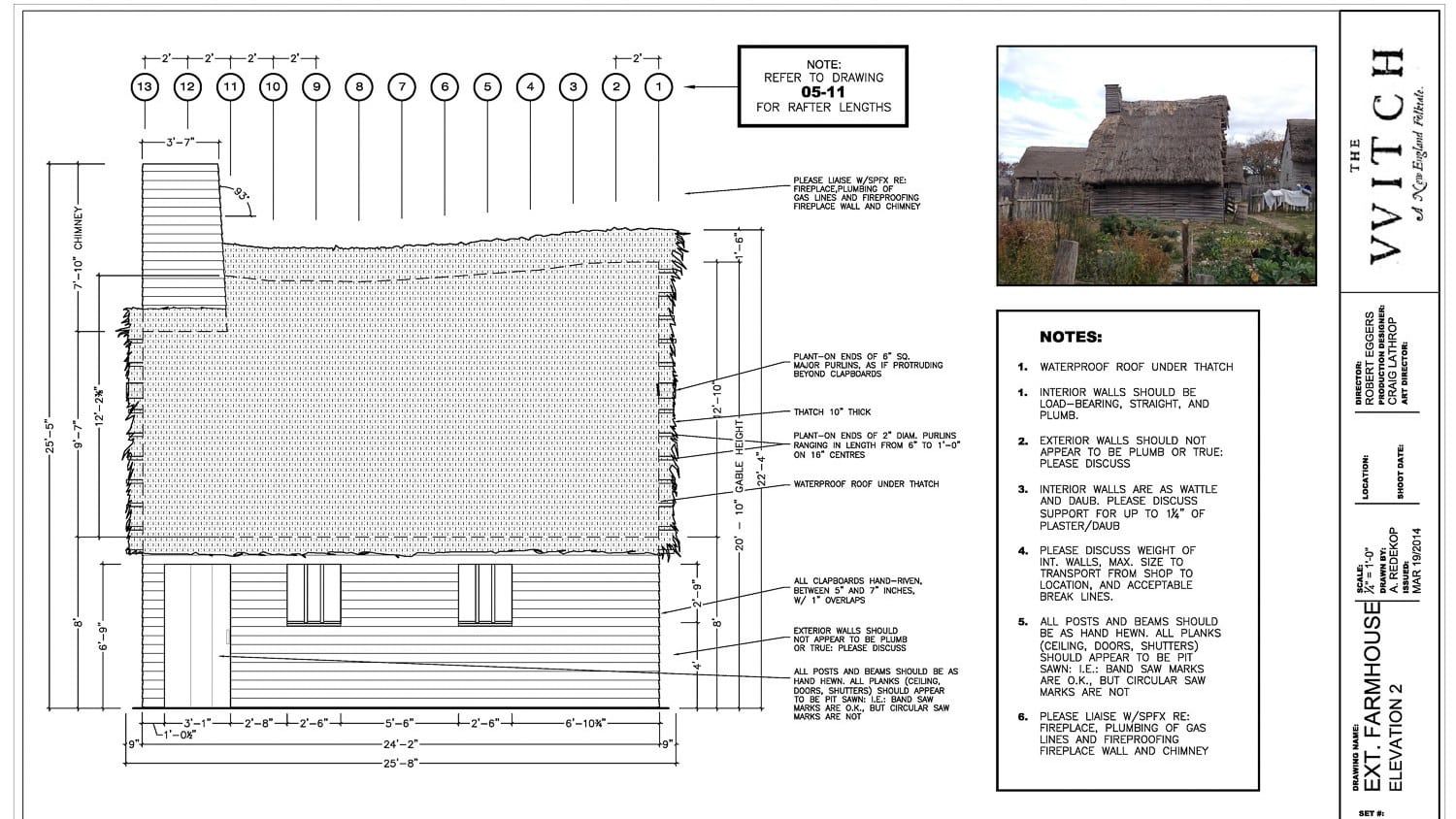

Decades before the Salem Witch Trials in 1692, The Witch lays groundwork for the rising hysteria that lead to women being burned at the stake. Eggers researched the time period for four years, off and on, before hiring a cast that could speak in accurate Puritan accents and designers who could build a historically viable 17th-century farm.

They only filmed by daylight or candlelight, recreated historical floor plans with era-appropriate tools and refused to use CGI animals. When we called Eggers to ask about the obsessive level of detail in The Witch, he was passionate yet flippant about his work.

“I’m a bearded hipster douchebag,” he said. “I was just eating a quinoa salad while I was talking to you. Is this movie my version of making artisanal pickles? I don’t know. Maybe that’s what’s going on here.”

There’s much more going on, however. We spoke about using wood cuts as source material, making lanterns from scratch and the sweet, pleasant smell of dung. He was, “open to talking about pretty much anything—aside from the satanic temples that support the film.”

On his start as a costume and set designer.

“I started working in theatre in New York—experimental theatre, street theatre. I always designed the sets and costumes for shows I directed because I liked it. I grew up wearing costumes to school until I was beat up for it. For Christmas, I asked for costumes instead of toys.

“I had some good costumes. There was a Captain Hook one. I went to school as Abraham Lincoln on President’s Day, one time. I mean, I was a weird kid. Whatever.

On working with production designer Craig Laithrop for The Witch

“Craig was the only person who showed up to the interview with the same kind of research that I had. Everyone else had a storybook misinformed idea of what early New England was like. Something based more on Nathaniel Hawthorne and TV movies than real history.

“Craig came in with floor plans of the oldest timber frame house in New England and stuff that archaeologists in Plimoth Plantation had been digging up. He really knew what the hell was going on.

In fact, when we went to Massachusetts on a field trip, he knew more than the museum curator. It was an easy hire.”

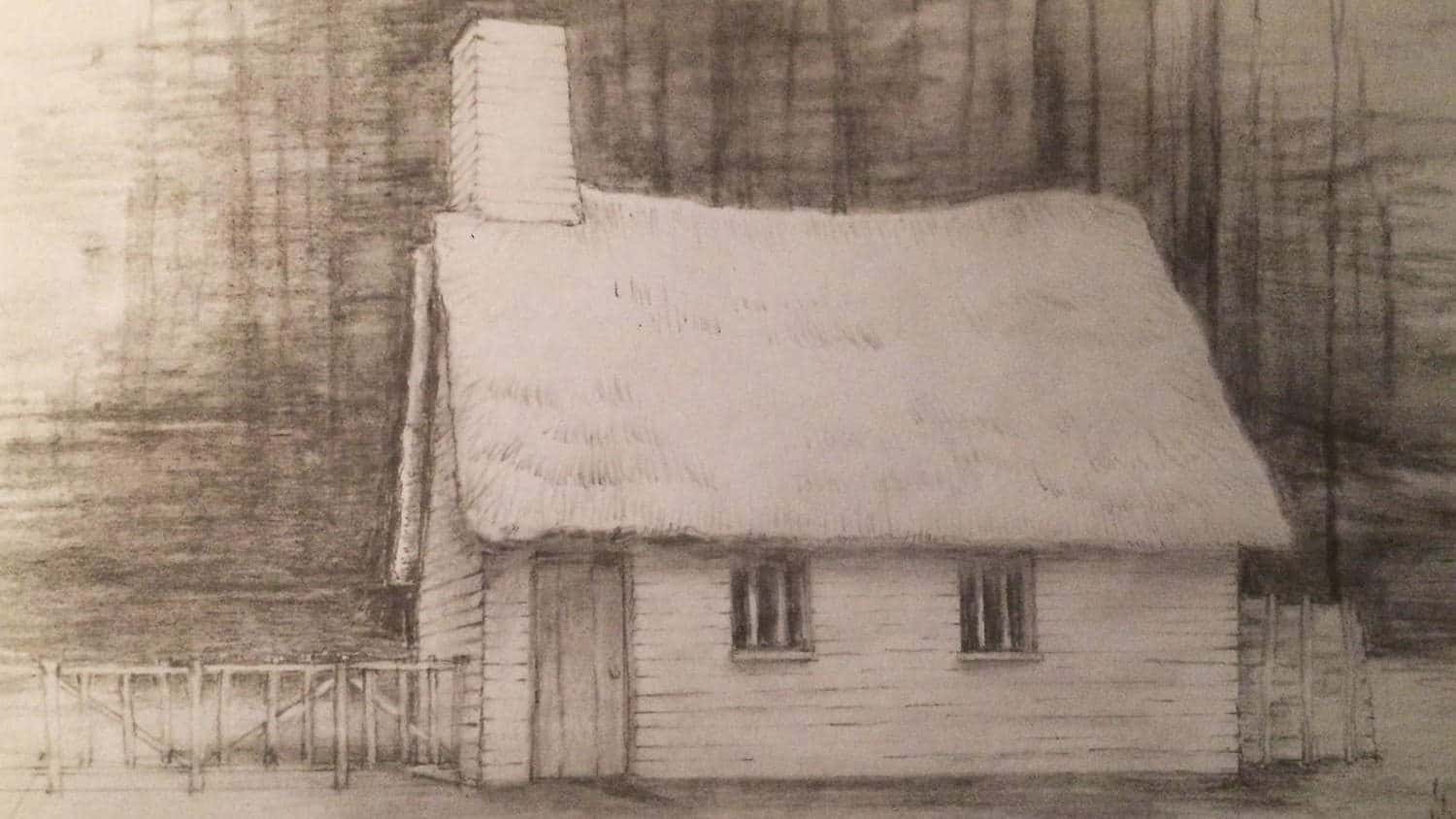

From left to right (via Craig Laithrop): farmhouse sketch, construction drawing, 3D model on location photograph and exterior film shot.

On why you need authenticity for horror.

“The plan was to make a world that’s utterly believable so that you can invest in the world and invest in the characters. You can be transported into their worldview as well.

“That’s what helps you believe in witches the way that these people would have. You can believe in supernatural stuff.

“Even the supernatural is articulated in a way that could, aside from a few shots, be explained scientifically. The movie doesn’t have a lot of bells and whistles.

“Furthermore, for filmmaking to really be immersive and transportive, it has to be so personal. In every frame, it had to be like I’m articulating my own personal memory of childhood as if I was a Puritan remember the way my dad smelled in the cornfield that morning and the way the mist was hanging in the air.

“How can I make it personal without obsessing over the way the saw marks look on the floorboards in the garrett? Those details matter if I’m trying to share something personal with the audience.”

On limiting his visual palette.

“It was a small location and there’s not a lot of characters. Clothing was only made of wool or linen. The other materials are wood, mud, dung—there’s not a lot of variety to choose from.

“Even though there was no painterly tradition in New England of rural people, I did sometimes turn to Dutch, Flemish and French paintings that showed the lives of poorer people.

“The source material from the English was wood cuts of scenes. It’s interesting to start questioning history. You think you know what a Puritan collar looks like because of Thanksgiving cards in grade school. Then you look at a wood cut and you’re like, ‘Hmmm I don’t know about that.’

“We only shot with natural light and indoors, the only lighting was candles. It was an extremely limited palette that kept everything together.”

On sourcing lanterns.

“The lantern was tough. It’s easy to find that Sleepy Hallow, Tim Burton-type tin lanterns. You can get them at Yankee Candle. Those are more accurate the later part of the 17th century.

“I was looking for a more round medieval style that’s actually made more from wood than iron. Kate, the props master, spent a long time making a lantern half from scratch and half from something she found.

“She tried to recreate the panes that would have been made from horn, and not glass. Real horn was so opaque that we didn’t get enough light for exposure, so Kate took panes of wavy glass and painted it with translucent paint to emulate horn but still give exposure.

“I was terrorizing her about the lantern, but in the end, she did a fucking incredible job. I really am pleased with it.”

On the smell of dung.

“I write a lot of smells in my screenplays. In my dreams, the smells are always so important. The Witch has a smell from the constant burning hearth and dung. Those are the main smells.

“The familiarity that people had with dung was huge. Dung to someone in this agricultural world could be a very sweet, pleasant smell because think about what the dung is doing for your crops.

“People were saving their urine to ferment into ammonia and cleaning their clothes with it. You would even save human feces because if you kept it for a year, you can grow root vegetables in it.

“So, you know, shit was all over the place.”

On sleeping on set.

“Sadly we didn’t. I really wanted to do that, to dress up like pilgrims and stay there, but other things were more pressing so that never ended up happening.”

On designing The Witch’s title sequence and posters.

“I designed the title treatment. All I did was take the way it says “witch” from a Jacobean witchcraft pamphlet and then cobbled together the subtitle by pulling individual letters from a Milton publication.

“Luckily the production company A24 thought it was cool. I didn’t think they were going to feel comfortable using two “v”‘s as a “w” (even though that’s what you see in many period texts) but I’m glad they did.

“I would have preferred a marketing campaign of only wood cuts. The vinyl edition of the soundtrack is only wood cuts and it’s much more how I wished everything looked—but A24 made the right decision. It was very collaborative.”

On his next project.

“I’ve been spending quite some time in the Middle Ages working on a medieval knight film.

“It’s really fascinating because people think about people in the past as being unsophisticated, but they were so sophisticated.

“When I went to the Globe Theatre Museum, they had this doublet made in silk and explained that no one in the world knows how to make silk like this anymore. The secret’s been lost. It’s so fine and so delicate and no one can do it.

“The same is true with some armour. When people try to recreate it, it’s so finely made that it can’t be done. The joint are so little. If you’re off by 2mm, the whole thing doesn’t work.

“The finest chain mail in the period was completely flexible but you couldn’t put a pin through it. It’s amazing what humans are capable with limited tools and mastering those tools.

“Today people don’t have a lot of craft. It’s mostly collage and reappropriation, so it’s interesting to go back and learn about when that wasn’t the case.”

All images courtesy of A24