There are two kinds of light—the glow that illuminates and the glare that obscures.

I am Kotaro Abe, a Japanese designer living in London. For my project “We Want More Sunlight,” I embarked on a nine-month quest to find the value of sunlight in modern life. From living in darkness to cooking eggs with direct solar power, I performed “rituals” to understand the sun’s physical and psychological effects on a human being. Plus, I designed a few inventions along the way.

There were two reasons for this quest:

1. Seasonal Affective Disorder

Moving to London was a huge life transition. Coming from the “Land of the Rising Sun”, the amount of sunlight I got in London was simply not enough for me to sustain my mental health. I felt myself gradually become more introverted.

However, as “the feeling of thirst teaches us to appreciate water,” the symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) made me realize the importance of sunlight for the first time in my life. And made me interested in the effects of sunlight on my creativity.

2. Interactions with Human-Made Nature

Living in this technological era, where a lot of our environment is replaced by digital phenomena, the amount of time we are exposed to sunlight is limited thanks to the artificial lights. These amazing inventions have brought brightness to the darkness of night; which consequently have led us to lose our diurnal cycles. Most of the people in urban areas don’t even have a idea of dark night anymore, as these artificial inventions follow us through the city. I started asking myself, “Is this really the right thing to do?”

Taking a Holiday From Sunlight

My first step, in September 2016, was to take a holiday from sunlight.

I took a completely dark room and added a fake window with an LED light. This human-made contraption is critically different than natural sunlight. When the LED brightened to mimic the sunrise, it lacked freshness. This is because the light wavelength of LEDs are limited compared to sunlight, mainly lacking in the UVB waves that induce serotonin in our brain.

After living in this room for two days, I had insomnia for two weeks.

Eat Your Fish

After the “Holiday from Sunlight” experiment, I started wondering about the people who live in extreme lack of light environments. A simple Google search (“world,” “least,” “sunlight,” “city”) turned up the city of Reykjavik—so I booked a flight.

Reykjavik is the capital of Iceland and has the least sunlight hours of any capital city in the world. On the winter solstice day, Reykjavik only has four hours of sunlight above their horizon. Since the sun would never be high enough to light the island in winter, four hours of daytime in Reykjavik is weirdly blue. This blue sunlight is a problematic for our body since it doesn’t contain the UVB you need to get vitamin D. That is the main reason why in northern altitude countries, there are a lot of patients suffering from SAD. However, to tackle this perpetual cause, there are also a lot of ways to compensate the lack of vitamin D such as SAD lamps and vitamin D tablet supplements.

During my interview with professor Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir, at the faculty of Icelandic and comparative cultural studies at Iceland University, she pointed out that Icelandic people have centuries of knowledges to cope with the harshness of a cold and dark winter for both mind and body. What do they use? Literature and fish.

The country’s best known literary tradition is the Sagas of Icelanders. Guðmundsdóttir says that when people are forced to stay indoors, these stories create another world that keeps communities intact with reality.

Then, there’s the fish. Iceland’s industry accounts for 2.1% of the world’s fish and it ranks 12th worldwide. It’s the second largest industry in the country and employs 4% of the total population. However, the fish is not only effective on economical level. It’s also important for getting vitamin D they don’t get from the sun. Oils extracted from fish, called “Lysi,” is far more natural than taking synthetic tablets. For the people in Iceland, catching more fish means getting more sunlight.

Inspired by the relationship with their industry and the sun, I decided to design a prototype to catch more sunlight on the winter solstice day in Iceland. Getting help from local design students, I made Suncatcher objects.

The sun is there, but as the invisible source of light, in a kind of insistent eclipse…One may not look upon it, on pain of blindness and death. Beyond that which is, it portends the Good, of which the sensible sun is the offspring: source of life and visibility, seed and light.

Sunny-Side Up

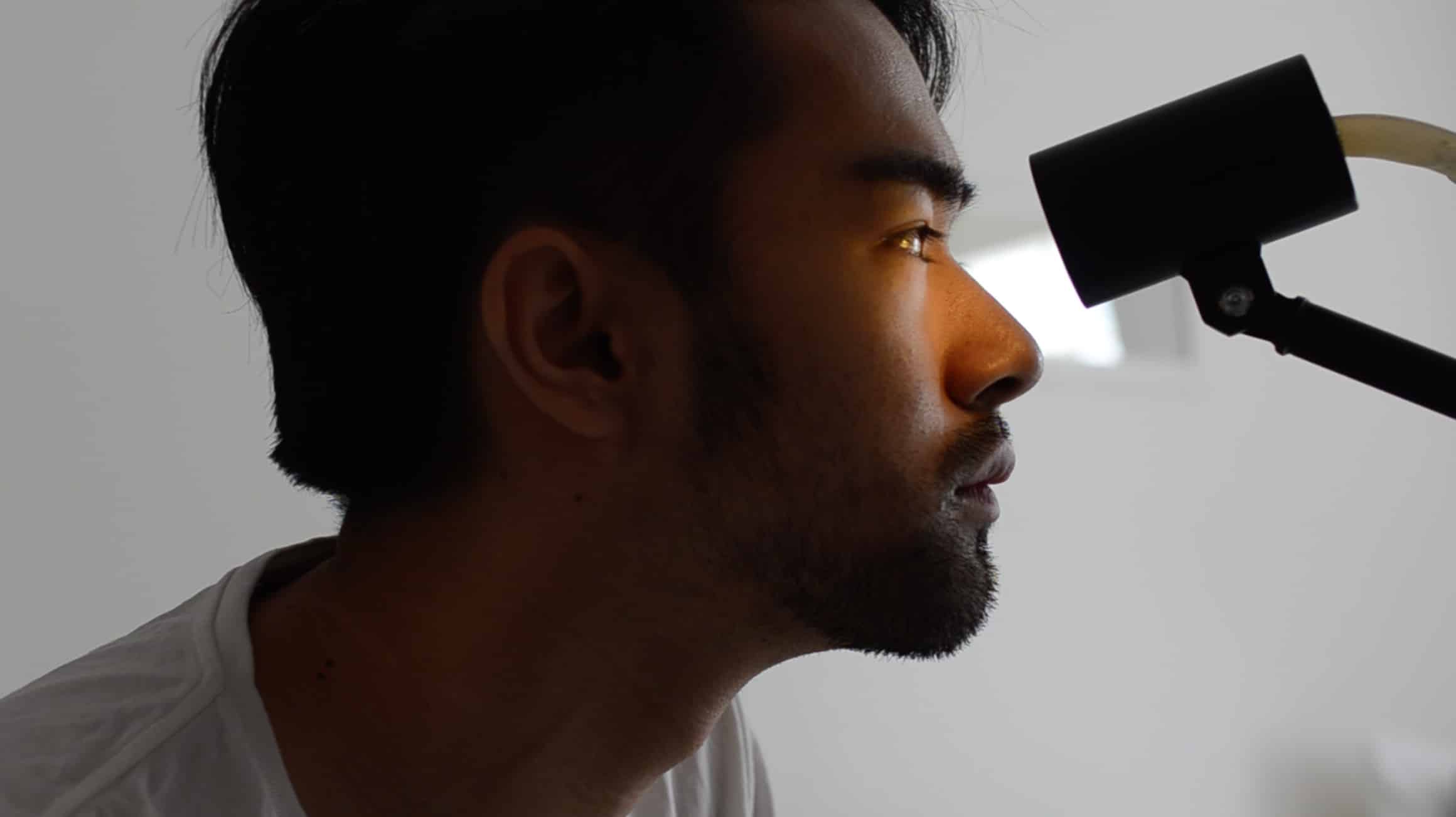

By the time I got back to London, it was February and the days were getting longer. This is when I decided that I wanted to eat as much sunlight as I could I was going to make a sunny-side up egg with sunlight.

The origins of an object have significance—take the Olympic flame, for example. Although it’s essentially the same elements as the fire from your gas stove, the origin of the fire starting in Olympia, Greece feels monumental. I believed that using sunlight would amplify the mental effects of this psychological experiment.

However, this is still February in London. The light from the sun was not intense enough for me to easily cook an egg. For more than two hours I had to keep this same posture (pictured above) to keep the incoming light focused.

Although the outcome might taste same as the one cooked in your house, I can definitely say that the egg made by direct solar power certainly rejuvenated my appreciation for the products of sun—heat, light or food. The ritual was successful in connecting me to the sun, but it was too complex to do continually. Two hours to make an egg in the morning just isn’t realistic.

Lamp as Critical Object

It’s not like I am saying that we all have to go back to the past and start worshipping the sun. But look around you—most people reading this will be sitting indoors with some kind of artificial light on. For example, I am sitting in the cafe near my house in West London. It is 1 p.m. and typical gloomy London weather.

Despite the bad weather condition, sitting next to the window is providing me more than enough brightness to write down notes and sketches. Further from the window, there are dark spaces that sunlight doesn’t reach—for these spaces, we use the artificial light to sustain our visibility. These artificial lights in daytime are often designed to supplement sunlight or even replace the functionalities of sunlight.

For my next ritual, I wanted to investigate the effects of a life surrounded by sunlight replacements. How do we go from “sunlight” to “sunlight”, rather than “sunlight” to “electricity” to “artificial light.”

My design is pretty simple. The whole system is divided into two parts; receiver and lamp. In a receiver there is a Fresnel lens which enables sunlight to gather in a spot to the edge of a fiber optic bundle. The other edge of bundle is inserted into a lamp which you can either put down or hold in your hand.

I used the lamp both as a normal lamp, and a critical object that reminds me of the existence of the sun. My subjective awareness to sunlight was amplified and seemed like it had positive psychological effects. In terms of physical exposure, the brightness solely depends on the intensity of sunlight and with cloudy weather, the light is barely recognizable. However, unlike conventional lamps, it doesn’t ask for any electric circuit and battery, and in terms of energy transformation it is safe to say that it’s a green device.

Sunlight Fast to Feast

As the days approached the summer solstice, I wanted to cherish my quest for sunlight by creating a ritual that maximizes my exposure. I contacted Dr. Lewis Daly, a researcher of anthropology at the University College London. I told him what I have done so far, and the intention of my next ritual. Although he seemed bewildered, his reactions to my project were overall positive, and he started to explain how humankind has long treated the sun as a subject of worship. In history, the acts of sun worship have existed in so many different cultures and one of the things that they have in common is the idea that “the sun is origin of everything”.

It is not easy to imagine what the life on earth would be without the sun. No sunlight means no light and heat, and means there’s no photosynthesis. We cannot grow any foods that consists of our body. Or there are not even bacterias if it were not for the sun. Even though too universal to be aware of, we cannot live without sunlight. Even in this 21st century, we should never overlook the such a cliche fact ‘sunlight is important’.

Daly pointed out the example of religious fasting—abstinence from eating is followed by feasting. In my persistent journey to track sunlight, he suggested that I go from extreme dark in order to enhance the maximum exposure afterwards.

In June 2017, I made a completely dark room in my house and started a one-day fast from sunlight.

In a book Nine Habits of Happiness by David Leonhardt, he writes, “Thirst teaches us to appreciate water. Fatigue helps us appreciate sleep.” I believe in this ritual, darkness made me appreciate sunlight.

I stayed in the room for 24 hours without any light or food. (For safety reasons, I had water). I endured this hardship waiting for the next day when I would counteract with a full day of sunlight. From dawn to dusk, I soaked up sunlight on a rooftop in central London and felt the glorious effects.

After nine months of rituals, prototypes, and design inventions, I wondered if I accomplished my quest. If I truly understood sunlight any better. The answer is, I don’t know. But, through this whole journey, I recognized over and over again the meaning of living with sunlight, and why I will always seek out the real stuff when I can find it.

Visit Kotaro Abe’s portfolio here.