America has a nostalgia problem, most recently evidenced by the “Make American Great Again” campaign slogan that put Trump in the White House. Great swathes of the country are dewy-eyed for a post-war social and economic landscape that has yet to see the disbanding of American industrial manufacturing and the constituent middle class.

We all know the plot. Scene: Post-World War II: Industry is booming and the American middle class is happy in their avocado green and harvest gold Levitt homes. Suburbia, fast food culture and the concept of “teens” are evolving.

We know what follows—low-cost imports, the elimination of trade barriers and outsourced labor. The promises of late capitalist expansion slowly and surely chip away at the middle class and its trappings. The remnants are disenfranchised and angry, nostalgic for a pre-globalized American economy where you could still go on vacation or buy a car without having membership to the economic elite.

The result is a dominant fondness for the aesthetic and culture of mid-century American life, and a willing forgetfulness of the chauvinism, consumerism, conformity, racism and nationalism that existed alongside and within America’s booming post-war manufacturing industry.

The problem is that America’s nostalgia isn’t discerning, as nostalgia seldom is. It’s not just the post-war economy that people are fondly conjuring up, but also the social and cultural landscape of mid-century American mass culture and its codes. Loud conservative voices have tapped into the sense that things used to be better (and maybe things were, economically, for white people in middle America) to propagate a sense that everything used to be better.

The result is a dominant fondness for the aesthetic and culture of mid-century American life, and a willing forgetfulness of the chauvinism, consumerism, conformity, racism and nationalism that existed alongside and within America’s booming post-war manufacturing industry. And this all encompassing nostalgia isn’t just relegated to conservatives in middle America.

There’s a certain cognitive dissonance happening among millennials, who lambast oppressive social structures, then non-critically fetishize—through art and fashion—the aesthetic and mood of the periods of time during which these social structures flourished. Fashion photo spreads and nostalgic Buzzfeed quizzes appropriate emblems of classic Americana in ways that subdue or forget original contexts. We love the seventies right now. But do we?

So the question becomes: how can we dig the aesthetics of mid-century fast food culture and suburban anti-taste, while simultaneously acknowledging the dark social underbelly of the period?

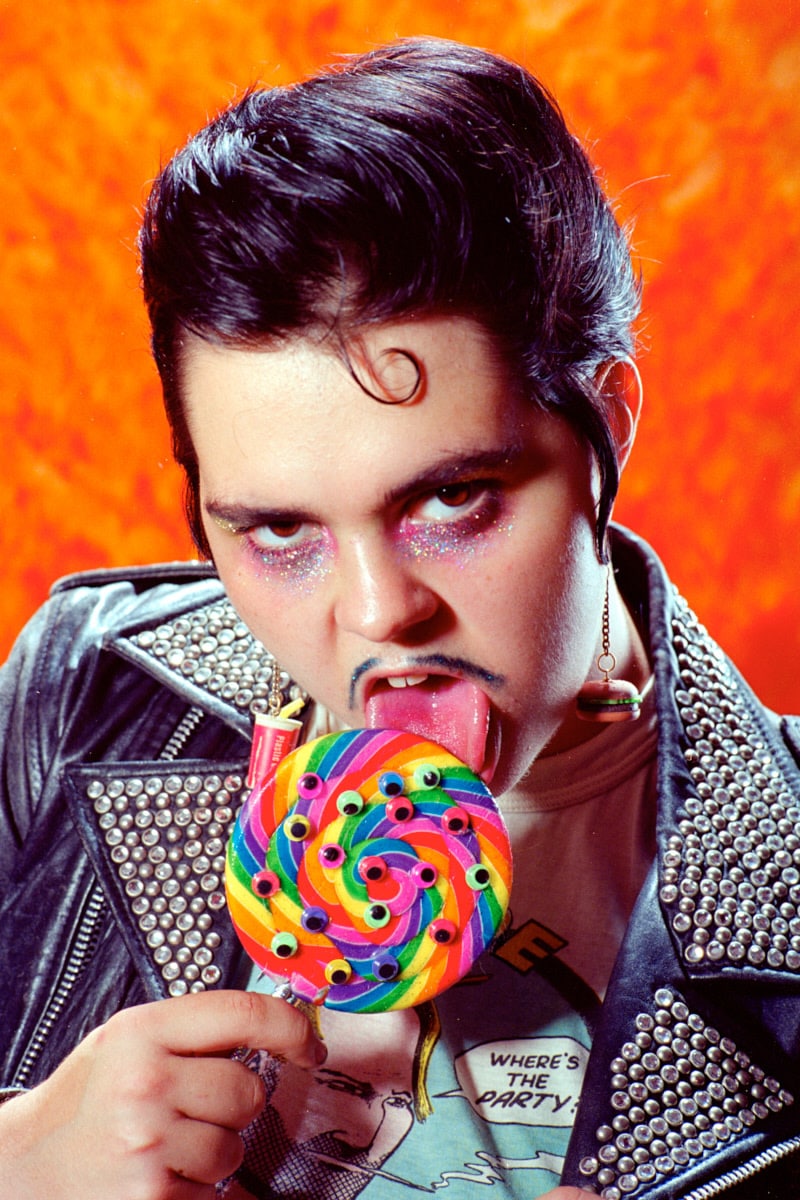

Cue Nadia Lee Cohen, Scarlett Carlos Clarke, Eloise Parry, and Parker Day. These four emerging artists are reimagining what nostalgia can look like in contemporary culture and making it political. They’re giving mid-century aesthetic an uncanny treatment through employing imagery that delves into the seediness, the bad taste, and the unpleasantness of decades past. They lead a new generation of photographers who are ushering in a more underbelly-baring sort of nostalgia.

Their images reflect common tropes: housewives are sexy, but also deeply bored, maybe on drugs, and hyper-saturated in color schemes that hurt our eyes. The retro styling of their work is equal parts hideous, sinister, and appealing. Subjects are non-conventional, bathed in tell-all lighting, and situated in kitschy-retro-detritus set-dressing. John Waters, David Lynch, and Stanley Kubrick linger beneath the surface. Something’s not right, and we can’t help but remember that America has never been perfect.

The retro styling of their work is equal parts hideous, sinister, and appealing.

Nadia Lee Cohen

Hailing from Britain but now L.A.-based, Nadia Lee Cohen does uncanny nostalgia to the nines. Recently a recipient of the prestigious Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize, she dabbles in the sort of American tokenism that makes your skin crawl: think Lana Del Ray on amphetamines in a fun house mirror. Her recent campaign for British design house Zizi Donohoe features feet in fur slippers with talon-like polished toenails, all against a backdrop of putrid shades of shag rug scattered with cigarette butts, half-eaten tv dinners, and unsettling beauty products.

Eloise Parry

Eloise Parry, who works closely with up-and-coming fashion designer Claire Barrow, has carved out a space for herself as a bad-taste connoisseur. Parry and Borrow dropped a short film this past year titled Move On (watch it above), a piece of work that makes use of Parry’s penchant for foregrounding the strange, the ugly and the sinister while exploring styling from yesteryear.

Scarlett Carlos Clarke

London-based photographer and filmmaker Scarlett Carlos Clarke draws inspiration from the past to create bizarre, repellent and fascinating images that fetishize and problematize housewives and fast food. In her series Body Dysmorphia, she explores self-policing female perfection using a visual language that references mid-century beauty standards.

Parker Day

Parker Day shoots exclusively on 35mm film, and works primarily in portraiture. Her fictionalized characters occupy a seedy neon world comprised of the trappings of night-life weirdos and old-school freaks. She activates a similar sort of anti-aesthetic, anti-nostalgia as her peers, and derives inspiration from underground 60s comics and dystopian sweetness.