Photographer Leonora Baumann recently finished a series about child mothers in Congo that has not gone unnoticed. At Baumann’s exhibition in Chicoutimi, Quebec, Blink’s photo editor Laurence Cornet talked to Baumann about her beginnings, and the challenges of photography in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Laurence Cornet: You studied commercial photography. What made you pursue photojournalism?

Leonora Baumann: At the end of my undergraduate studies, I assisted Cedric Gerbehaye, a photographer from Agence Vu’ who had just finished a long-term project about Congo. He was in the process of releasing his book and opening a corresponding exhibit for the 50th celebration of Congo’s independence day. Working on that collection inspired me to go into reportage.

Visa pour l’Image, the launch of the French magazine 6 Mois and the talk that Wilfrid Esteve gave around the same time on new storytelling tools really inspired me as well. I started to work with sound by letting my subject’s voice in, to tell their stories. Someone’s words are something you can’t have with just a photo.

After receiving my Bachelor’s degree, I worked on a story about a street juggler in Brussels named Hicham. I followed him and documented his daily life by capturing his encounters with other performers, the place he squatted and the difficulties he was going through. The project included a multimedia piece to accompany the photo series.

LC: What took you to Congo?

LB: My work on Congo came after I studied multimedia and documentary. I received an internship for a Kinshasa newspaper called Le Potentiel. Kinshasa is a rather small community and so through my work I met potential commissioners and quickly received assignments. There is a big need for images there, and local photographers are not always available or specialized for particular projects. For example, I worked on a project for UNHCR about Congolese being sent back to Congo from the Central African Republic (CAR), and about CAR refugees crossing the border to Congo.I was also working on a story for Radio France about the Symphonic Orchestra of Kinshasa. The discovery process of that story inspired me to look for my own stories.

So, I started with a short reportage on the Capoeira dance. As a result of the transatlantic slave trade, the dance started in Brazil but finds its origins in Africa. Capoeira is danced here among street kids as a form of social bonding.

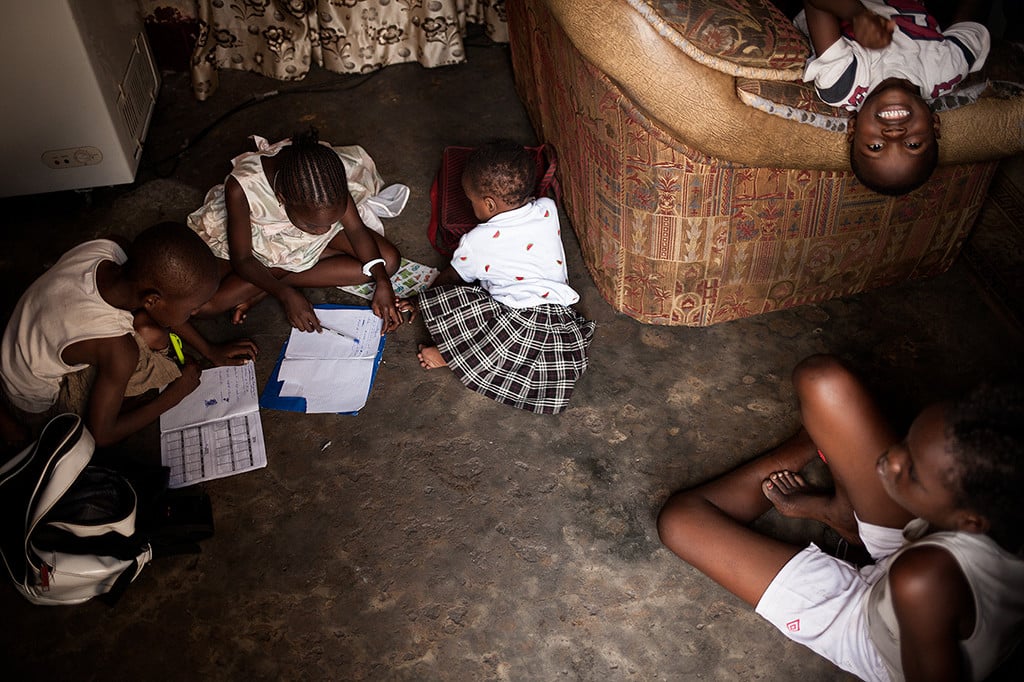

Around the same time, I started to investigate the issue of motherhood. Motherhood feels particularly important in the Congo, which has a high birth rate and a high infant mortality rate. I traveled East to Goma, a region at the heart of the country’s conflict for the past two decades. Working on child mothers in Goma allowed me to cover the conflict in a less direct way.

LC: How did you pursue this series about child mothers?

LB: UNICEF helped me gain information and access. They told me about the House Marguerite, a home for child mothers. It took me a long time to find the place because nobody knew the address of the house. I love this treasure hunt aspect of photography. As photographers, we don’t know where we are going, but, when we make discoveries—stories take shape. I found the house just before flying back to France, and I knew I wanted to go back. Eight months later, I managed to cover my trip by working on assignments for a few NGOs [Non-Governmental Organizations].

LC: What is it like working with NGOs?

It’s a very different way of working. NGOs usually look for very illustrative photographs. The main advantage is that they provide very privileged access to important stories. Depending on the NGO, I had more or less time to find stories and meet people. I went back last month for Medecins Sans Frontieres. They look for photographers in the Congo because they cannot afford all the travel expenses. However, recently, they have offered to cover my flights. I love working for them because they give time to fully develop and explore my stories. During that process, I talked to many people and dug into issues that I didn’t know about. Now, I really want to go back again.

LC: You work both at home, in France, and abroad, mainly in Congo. How do they complement or inspire each other?

LB: I always dive into the story I work on whether in France, where I recently followed a circus troupe for Neon, or in Africa. It’s always a discovery of an unknown universe. The more you travel, the more you realize that there are many things happening all around you. Simply realizing that, means you somehow travel when you are back home as well. Traveling arouses curiosity, and you bring this curiosity back home. It is one of the wonderful things about photography.

LC: What did you discover in Congo?

LB: What first struck me was the spontaneity and the happiness of the people. Of course, the situation is more complex. People survive but have no vision or hope for a better future. Congo is a very rich country in terms of natural and intellectual resources. However, I found some of these resources unutilized. Most young people in cities went to university, but most of them end up unemployed.

In terms of working there, the first challenge was dealing with Congo’s perception of photography. Photography was historically forbidden there, and this ban is still in the back of people’s minds, particularly in cities. Also, while it’s hard not to feed the Western clichés vis-a-vis Africa, it’s also very hard to go against the Africans’ expectations for white people. Congo has nearly no tourism so there are negative stereotypes associated with white people.

LC: That being said, was it hard to get the security guards’ permission to be photographed for your portrait series?

LB: Everybody agreed, probably because I always took time to chat with them. When I first arrived in Congo, I was very uncomfortable with the fact that I had a cook, a driver, a security guard and so on. It’s disturbing. But there, every house with a certain standing has a security guard, usually standing in front of the house under a mosquito net.

What gave me the idea for this series were the security guards from the first house where I live in Kinshasa. They wore hoods and gloves at night to protect themselves from the mosquitos. I found it both scary and funny. Anyway, when I started to ask other security guards if I could take a portrait of them, they all agreed. They wanted to tell me their stories, to talk about their families and their studies. They thanked me for chatting with them.

LC: Do you plan on merging narrative and photography for that series, or in the future?

LB: For that series, I wrote everything down in my notebook. I wanted to associate their portraits with information about them. In general, I think that there are plenty of possibilities to tell stories with photography. You can either use new technologies or old ones in completely different ways. It can always add to a story and may help in its distribution.

I would love to develop a web documentary, because it would give me the opportunity to work along with a team as I miss that collaborative element of my training years. It is a completely different dynamic to bring together various views and skills around one project. In the meantime, I am trying to develop my language as a photographer—I don’t see all my projects as a multimedia pieces. Photography is extremely powerful by itself!

Blink is a real-time location platform that enables media companies to discover, connect, and organize a global network of media professionals. Find out more here.