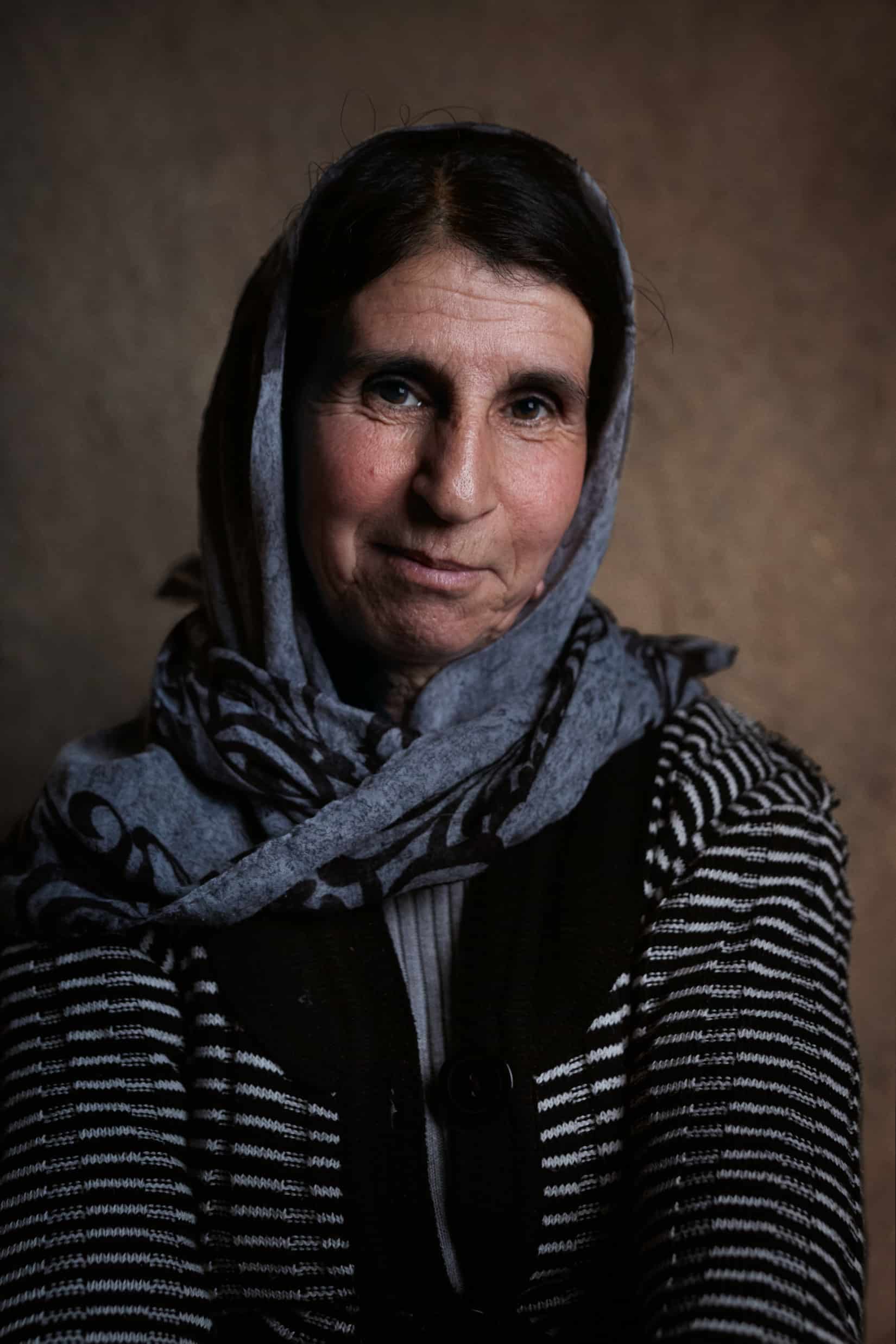

No stranger to hostile environments, photographer Benjamin Eagle’s recent project #IamYezidi focuses on the Yezidi women who were held captive by ISIS. He spent five days in Iraq photographing the portrait series. The resulting exhibition took place in London last month, and featured the images alongside snippets of the women’s personal stories.

As reported by the UN, the Yezidis or Yazidis an an ethno-religious group indigenous to the northern Iraq being targeted for genocide by ISIS. They’re killing men who refuse to convert and subjecting women held captive to “the most horrific of atrocities.” As a rare glimpse into the people affected by these crimes against humanity, Eagle’s work will linger in your mind long after you look away.

Based in London, Eagle specializes in documentary black and white portraits. His photography from Haiti, Ethiopia, and Myanmar effortlessly capture the character and humanity of his subjects. His work has been previously featured by The Guardian, BBC, National Geographic Traveller and Sony Pictures.

Format sat down with Eagle to talk about the lessons he’s learned working in challenging environments, how he deals emotionally with the subject matter, and his advice for photographers interested in creating hard-hitting work.

Format: Hi Benjamin. Your #IamYezidi series is incredibly poignant and requires access to a traumatized community of women. What were the first steps in putting together this project?

Benjamin Eagle: International humanitarian organization Khalsa Aid has been working with the Yezidi community in Iraq since 2014. ISIS view the Yezidi people as devil worshippers, and have captured and enslaved many women—some of whom have either escaped, or been sold back to their families.

Kanwar, one of the core team members, felt these women’s stories weren’t being heard. In January 2017, he asked me if I’d be interested in visiting the camps with him, to photograph the women, with the aim of putting on an exhibition.

Can you describe your experience visiting the camps?

The first camp we visited was Sherya in Northern Iraq. What struck me was, firstly, the sheer size of it, and secondly how organized it was—each camp had a manager and allocated teams for different areas. Classes were set up in various tents, and shops had been stationed for food and trade. We visited five camps over the same number of days. Some were very established, others were just basic shelters where people stay for a short period of time.

What was your stylistic approch for this project?

I wanted to create a basic stripped back portrait series that allowed for the women’s facial expressions to tell a story.

Throughout my previous travels I quickly learned the importance of the relationship between photographer and subject, which is usually displayed through the subject’s eyes. My favourite work always shows some sort of connection or understanding, even if I hardly know that person.

How did the women react to you?

The women we met had been asked in advance whether they would like to be part of the project, and they were keen for their stories to be heard. We had the help of Suzan, a young Iraqi woman who works in the camps. She translated for us and helped the women feel comfortable. The community has a great relationship with Khalsa Aid, so that really helped us gain their trust.

I wanted to capture the seriousness of the stories, but a lot of the outtakes were of the women smiling and laughing. It was hard not to use these as our leading images, but I decided I needed to show their strength and resilience.

A lot of the outtakes were of the women smiling and laughing. It was hard not to use these as our leading images, but I decided I needed to show their strength and resilience.

What challenges did you encounter?

The main challenge was light and time. Khalsa Aid was there to distribute aid, and the photography had be done afterwards, so we didn’t start shooting until 6 p.m., in dimly lit tents as it was often raining outside.

I really wanted to keep a consistent look across all the portraits, but in every home and camp we visited the lighting, back drop and space changed. We were lent a rug by one of the families as a backdrop which helped with consistency. One of my cameras also broke, but luckily I had two others on me.

How did the project affect you on a personal level?

It was incredibly emotional sitting with the women and hearing what happened to them and their families. Often, the stories were beyond anything I could even comprehend, and I was struck by their strength and positivity despite all the pain that had been inflicted on them. Some of their stories will stay with me for the rest of my life.

Shooting in these types of locations is always challenging. You see a lot of things, and I’ve struggled with nightmares and guilt. It’s hard to return home and go back to your comfortable life. You can feel a sense of detachment. But knowing you can get people’s stories out there and make a difference makes it worth it—our Yezidi images were shown at the British House of Commons a few weeks back and just seeing the turnout and people’s reactions was amazing.

I’ve struggled with nightmares and guilt. It’s hard to return home and go back to your comfortable life.

What did you learn from the project?

I got a much deeper understanding of the conflict and how complex it is. I thought ISIS was just a group of guerilla fighters, but they’re actually a very well-financed, well-armed regime—it was shocking to learn how powerful they are. They psychologically manipulate and control people out of fear. However, it’s almost so complicated that you can’t ever understand it fully, you can only understand people’s stories and perceptions of it.

At the same time, visiting this country that has a lot of stigma attached to it in the West, you see how vibrant and welcoming it is, and how so many people are still living their day-to-day lives. I’d go back in a heartbeat if I got the chance.

Is any image in particular your favourite?

Yes, the portrait of Bafren Shivan [Ed. note: The header image] is my favourite. She was released last year and is now working to support girls who’ve just arrived in the camp. She has an amazing energy about her, and I like to think I captured part of that in this photograph. You wanted to be around her. She’s a beautiful person.

What’s your advice for other artists or photographers keen to take on similarly hard-hitting work?

There are a lot of ethical issues surrounding conflict and documentary photography. Do your research properly, don’t just wander into some place. You also need to focus on the reasons why you’re doing it—there needs to be more to it than just trying to make a name for yourself. Be respectful, work hard, follow your heart, have a positive approach and don’t give up.

Visit Benjamin Eagle’s portfolio to see more of his work.