Abraham sat down with Format while in production for an installation commissioned by the Toronto Biennale of Art and co-presented with Gallery TPW. The opening will be held on Saturday, September 21st, 2024. Check out the Toronto Biennale’s website for more information.

To view more of Abraham’s work, check out his Format portfolio.

Art Is A Calling

My name is Abraham Onoriode Oghobase. The name Onoriode is from the Urhobos tribe, from Delta states in Nigeria. This name means “who knows tomorrow”. I was born in Nigeria in 1979 at a time of an oil boom. So I was born around that time where there was just so much, so much money in Nigeria. But, at the same time, we were also faced with the military regime. The regime was in and out through the 80s up to 90s before we became a democracy when we got a democratically elected president of our state.

I grew up in an environment where there wasn’t much exposure to art. It was really about being proper, going to school. We were all meant to go into engineering or accounting. There were not a lot of museums or art institutions for kids to visit. I think we made do with just playing at the church. But as I grew older, I realized that I love music, I love arts. Naturally, I wasn’t inclined to be an artist given the environment I grew up in. The reason why I say this is because I strongly believe that art is a calling. It calls you. It’s not enough to know how to draw or to know how to paint or to know how to sing. I think it’s much more. There’s something supernatural that drives it.

Abstractions, Identity, and Post-Colonialism

My practice at its core is about post-colonialism. I explore identity and representation.

I use abstractions as a way to engage. I’m really interested in language and the philosophy of aesthetics. What does that mean? As I learned I appropriated certain languages from within the structures of books. That led me to my interest in knowledge production. At its root, this interest in production for me is the result of looking at being aware of racial prejudices around me. I grew up based in Nigeria, but as I grew older, I started traveling. And for the first time, I could tell the difference–OK, my blackness was a thing. As soon as I left my community, it became a thing. When I came to Europe and North America I was really confused. I realize that it [the racial divide] goes way deep. And, though I am black, I came from a different culture where my blackness wasn’t such a difference. I also came from a different history of production.

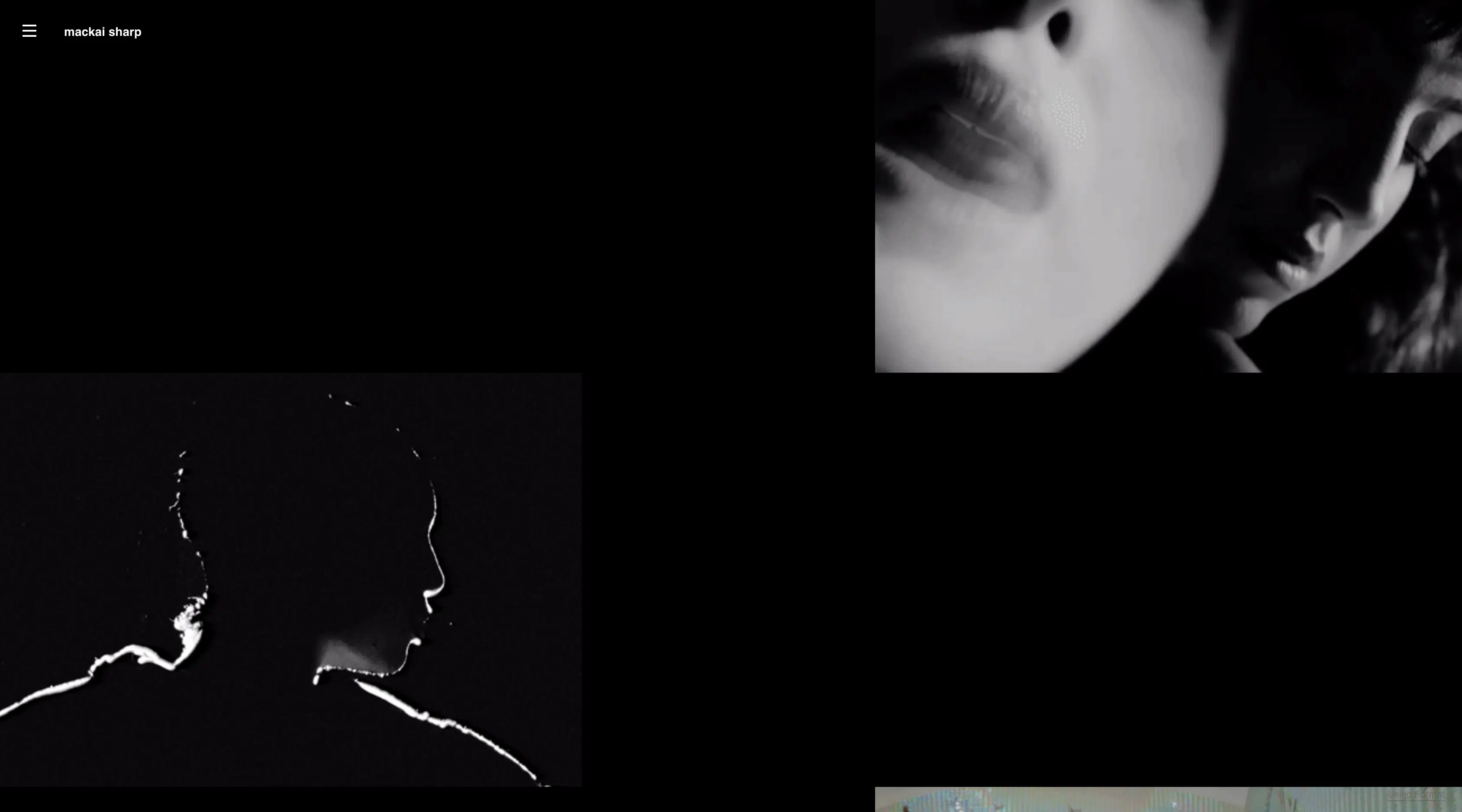

And I think that’s really how the shift in my work started. Because my practice used to be predominantly based in the aesthetic of the documentary format. When I started traveling to Europe around 2006–that’s when this awareness started. It made me really question a lot of things; my work, my practice. And then photography became really boring at some point, I just thought photography wasn’t enough. It was too two dimensional, it was too flat, to capture all of the layers of information and emotions and identities I was experiencing. Just capturing a representation wasn’t enough.

Sharing Personal Experiences Through Layered Imagery

II’m very captivated by music, specifically ambient music. One of my favorite albums is “Music for Airports” by Brian Eno. During my very first trip to Europe in 2006 a curator played that album to me and gave me the CD. I remember the first time I heard it, I cried. It was amazing that something could move someone so much that you feel something. And it wasn’t loud. It was tender, but also tough in its own way. So as I dug deeper into that type of music, I began to discover people like, Philip Glass and the rest of them, Steve Reich.

Through this exploration I became more interested in ideas of nothingness and quietness and stripping away previous notions of what photography is to me–thinking about the medium itself and how the medium could be elastic. At first, performance gave me a way to play with compositions and the structure of my work. Later, I looked for other ways to develop these ideas and then I realized that I could actually use repetition and collage to give depth to my ideas. I think the reason why my work shifted so much was because I was so connected to ambient music and the feeling that it gave me. I wanted to start making work that felt like that.

I now think of my work sonically, like I am a composer. Trying to make connections between what I see and how it makes me feel. This type of layered imagery allows me to explore big subjects–like violence on the land from mining, for example, but, this might be expressed through a photograph of a landscape that is repeated, distorted images of birds and land on top of each other. I’m more interested in the weight of emotion that this play of images can bring up. I don’t want to be trapped in this idea of literalness. I don’t want to reduce the work because it’s much more than just a representation of colonial history or a documentation of subjects like extraction, exploitation, the body, or land.

I’m trying to create something nuanced and layered that is very internal. I can only speak about my experience, right? I can’t speak about all people’s experiences. So it’s like – what do these subjects, what does the state of our world–mean to me? I go through the world from a particular lens. Going through immigration is different for me than it is for other people. It’s those small experiences everyday that add layers to our experience. These are structures that are put in place to humanize certain types of people and not others. Point blank.

This feeling goes into the way that I try to create the things that I create, whether they are personal experiences or they have to do with issues as large as nationalism. But it’s always about the internal. There’s something beautiful about it. I think this is also our strength as human beings, right? You know, we come from different places, different races, different backgrounds, different histories. But, there are similarities to our deep, internal experiences that are very similar–whether we like it or not, we are all connected–and it’s just amazing.

Sources of inspiration: Mentors, Books, & Schematics

Schematics have also been a device I use to talk about different frequencies in my work. I remember I was working with a famous Nigerian photographer based in Berlin, Akinbode Akinbiyi. He’s an elderly papa, you know, so he’s mentored a lot of us over the years. He gave me two books because I told him that I wanted to start working on the subject of mining in Nigeria.

One book was by Jane Mercy from Johannesburg, who does these sort of collaged drawings that incorporate photographs and paintings. The other book he gave me was titled “On the Mines” by David Goldblatt. The photographs in this book were just very frontal compositions. The directness felt very pure and I found them very inspiring.

Whenever I visited Akinbiyi he would take me to his favorite book stores in Berlin, they know him there. It was on one of these trips that I was shown this two volume book titled “Rand Metallurgical Practice.” This book was published in 1912. I started thinking about this huge two volume book that’s basically a methodological diagram that was used for the extraction of mines, both in Johannesburg in South Africa and in other similar fields, meaning the fields that they were colonizing, including Nigeria, the Congo, and other places, like Ghana. And it was fascinating. I never knew the extent of this history. I also never knew that this type of book existed. It was very mathematical, engineering, physics–but, it was aesthetically also beautiful. And so on that basis of aesthetics, I was like, “This is interesting.” But I didn’t know what to do with it or how to approach it. I had that book for four years before I did the work on the mines. I think the moment I started doing the work on the mines was when I started photographing those landscapes.

Just as soon as I started doing it, it started in my head, I started making a connection that the schematics could start going even on the landscapes. And then it just made sense to me, all the schematics could also become an animation of some sort. Then I started seeing the schematic again as hieroglyphs, as language. I was like, “Okay, I’m beginning to find some clarity with this right now.”

For me, those schematics are language, or, like some type of score as well. So I use them and collapse them into my imagery in different ways. Sometimes I even use them (like for the show at Hunt Gallery), as wall vinyl so they could also be seen alone. There’s a lot of possibilities that emerge when you begin to see how you can actually move things around and almost sample information and images like you are a DJ. It’s a similar strategy to music like hip hop–taking all of these layers from different places to create a new whole. And it’s just fascinating because what it does is that it creates depth, but also a certain type of abstraction emerges as well. All of the layers in the work create its own meaning in the work as well. They can no longer be seen in isolation–they create a faceted experience with depth.

Capturing Magic

I had one experience when I was photographing mines that I can never forget. I had been around shooting in the peak of the sunlight for hours and stayed until the sun set around 6:30. I climbed a hill and from far away you saw the little bus cross a hill. It was the same kind of hill I was standing on. It was a moment where things felt very connected–the light, the repetition of the landscape, and these electrical poles and things that used to power the mines.

I ended up photographing the scene from different angles. I photographed being on that hill, photographed the people that I met that day. Didn’t even know, but I just saw that bus, on this vast massive land, quiet land. And then you see the dust, it was such a beautiful moment. It’s one of those moments in photography where it’s like magic. Like I just knew I was photographing something really special. I just knew. I don’t say this too often, but it’s really one of my favorite images. And it’s not to say whether somebody collects it or not. That’s really what it’s just for me personally. It’s really, it was just a gift. That moment was a gift that I always just feel very thankful for. You know, I’m always thankful to God for blessing me with that moment–for that magic that happened.

Being Open; The Ability to Re-imagine

Being an artist is a struggle. It’s not easy. Because you’re looking for something. You’re searching for your true self. The result of this is just almost like a document of time, what we create. But we’re just in this business of fulfillment that also goes way deep. It’s a journey. And it’s something that I always want people to understand that art making is not a one size fits all. Everybody’s journey is completely different.

I think it’s also important for everyone to be open to other practices, to be open to other people, open to love. When we think about systems of power it’s important to reimagine or recontextualize. These are words I prefer over “dismantle”. Dismantle is almost to destroy something. You’re not destroying it, but it’s to–to disrupt it. It’s like an earthquake. Like you feel it, you know–you can feel it. You’re scared. All of a sudden you’re aware. It’s like, my God, you know, I could lose my life or something. I don’t want to create fear in what I create. I’m trying to find different ways in which I can re-imagine these structures of power, structures of representation, because that’s actually where the ultimate agency is.

Access and Engaging With Art Institutions

When exhibiting in institutions I think it’s important to have a dialogue. It’s important to be open, to learn from those institutions, right? To engage greatly with those institutions and to, in a way, gracefully question the systems, aesthetically in your work. But access is very important in dealing with these institutions. When you gain access, I think it’s important to realize that that’s already a major step toward a critical discourse. It’s something that I value. I feel like sometimes we have to come with a sense of grace and not with a sense of entitlement. We have to come with a sense of empathy to be able to engage those objects or engage archives in ways that doesn’t vilify but engages a global discourse that has to do with racism or systemic racism or institutional racism.

Access, as I said, is very important. And to gain this access, when you gain it, creates a road for the next generation. It creates a pathway for them. And we must understand that is also very much about pedagogy as well, and to be open to be able to teach those who come later. I think it’s important to be humble.

Education & Community

I finished my MFA at York University two years ago. Those days were so weird because just as soon as I got into the program, COVID hit. So I did my MFA during COVID and I graduated. It was terrible but you know like we made it work and I made good friends too. Even with all the restrictions, it was a great community.

I love Toronto. I love the art community. The art vibe is just really–it’s a small place. So it’s very easy for people to know each other. But I really love it here. It’s quiet. I can just focus on my work. I can travel, come back. It provides a great home base. Right now I’m working on a commission for the Toronto Biennale and co-presented with Gallery TPW. That’s what I’m really busy with right now. I’m in the middle of finalizing production for my installation of printed works, drawings and objects–entitled Onoriode (Who Knows Tomorrow?)–and it will open on September 21st, 2024.

You can watch part of our conversation here: