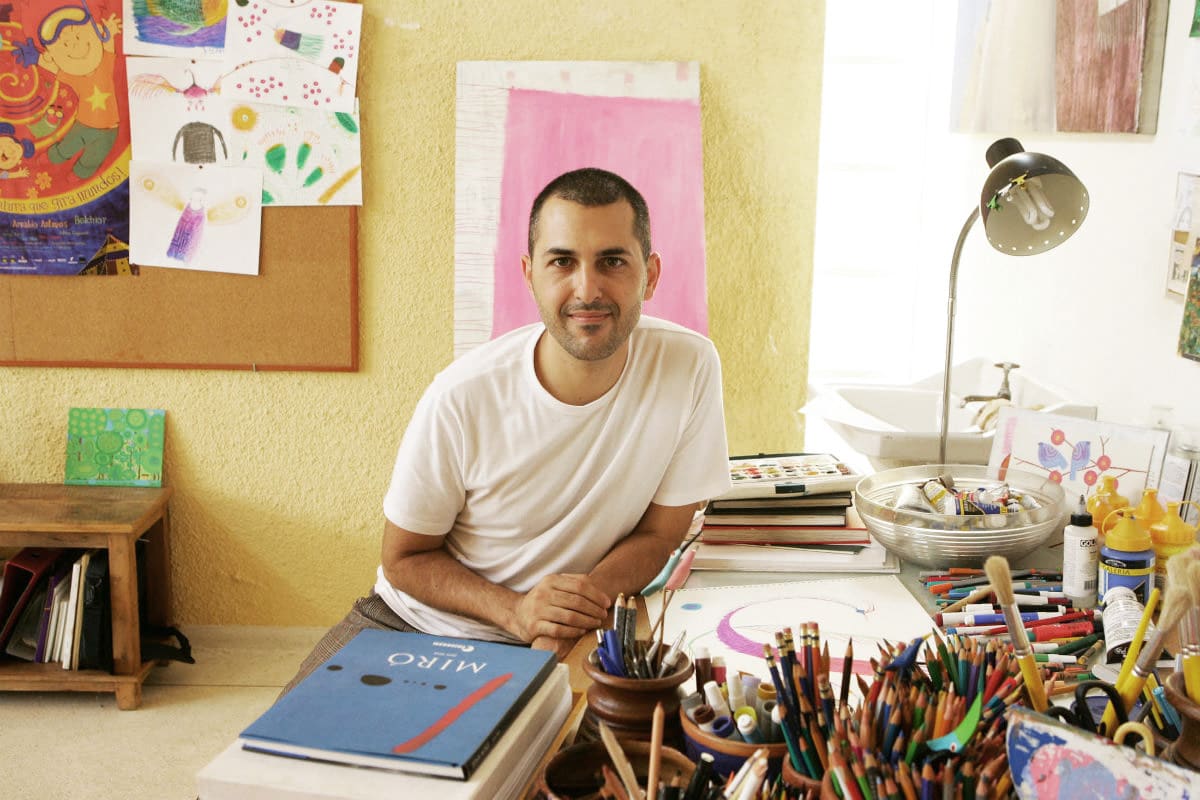

With his colourful and spritely animations, Brazilian film director Alê Abreu has a powerful visual language that he uses to talk about the political situation in his homeland. His second animated film, O Menino e o Mundo (Boy and the World), is an intimate look into the complexities of early Latin American history.

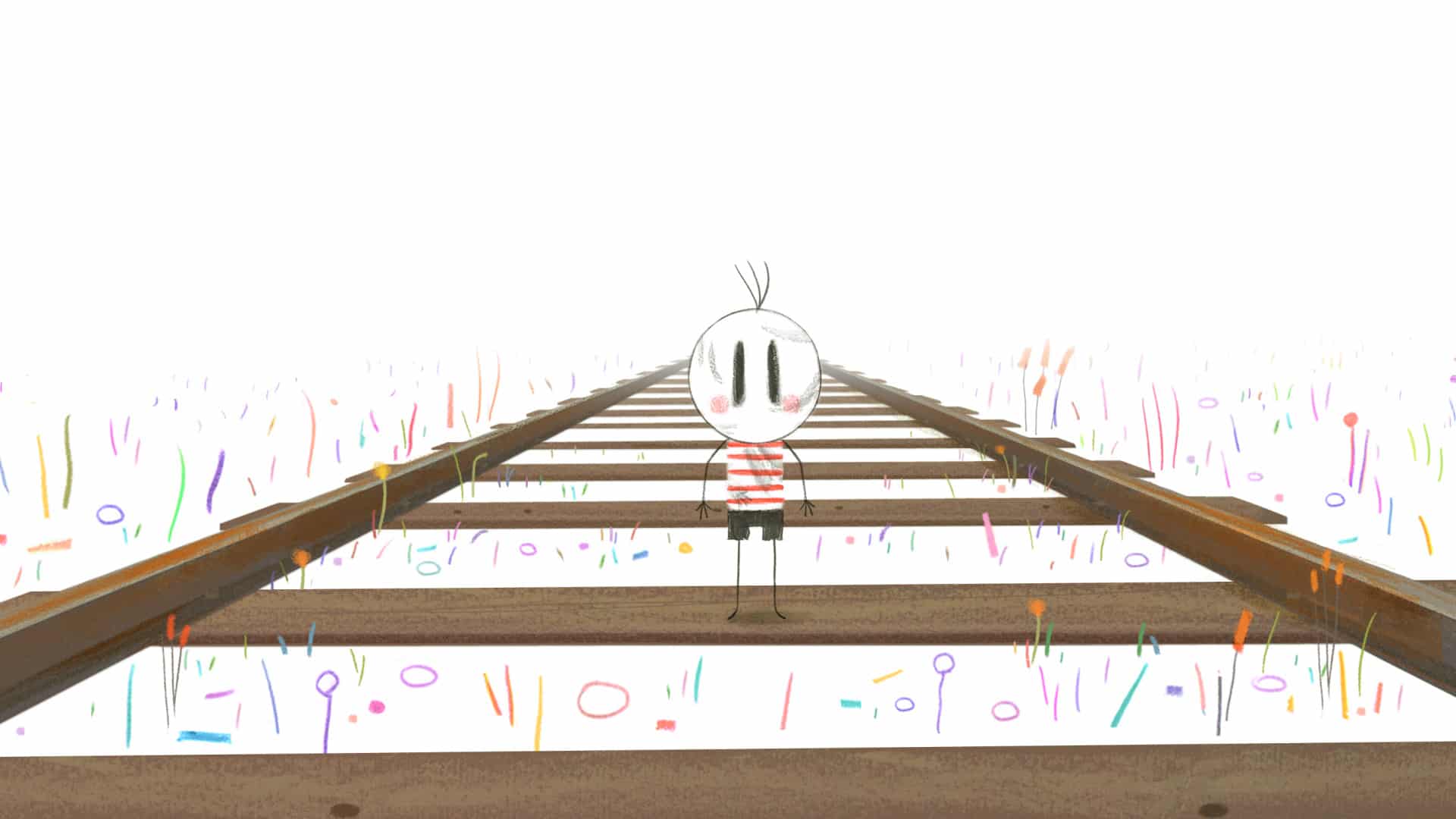

No matter where you come from, it’s an emotionally stirring tale. The feature-length movie follows a small boy from a mythical land on his quest to find his father, who has left in search for work. His journey takes us through different landscapes full of compelling characters, at the same time exploring the emotional impact capitalism has on families.

Despite Boy and the World having next to no dialogue, it speaks volumes. The film owes its loud voice to Abreu’s talent for storytelling and his rich, hand-drawn animation style. Nominated for the Best Animated Feature Oscar in 2016, it lost to Pixar’s Inside Out. However, Boy and the World recently beat out a Studio Ghibli film to win a prestigious Annie Award in the category of Best Animated Film – Independent.

Format spoke to Abreu about what went into Boy and the World, learning about the challenges of translating artwork to a digital format and the sketch that inspired the film’s main character.

Format: The style of your film is really beautiful, and is not often seen in animation these days. How hard was it to keep the handmade look of the drawings and the integrity of the textures when you have to work a lot with computers?

Alê Abreu: A huge part of the film was made with traditional techniques like drawing and painting, and with colored pencil, chalk, felt pens, and watercolors. I animated the film with computers using a digital pen, while still maintaining the textures and depth of the organic materials. I included these elements as a part of the characters.

The scenes were all made in the same way, although later we worked on them individually to separate the levels, depth of field, and transparencies. I always said to the team to see the computer screen as a piece of writing paper. We also used textures that were available on the digital tools, since they seemed real and honest.

There must have been happy accidents, nice surprises, or unexpected challenges during the three years it took to complete the film. Can you describe a bit about your technical journey while working on this?

Yes, the film had many surprises during the production, mainly because it was being made in a non-traditional way: we started the production without having finished the story. The film was made without a written script, and we created the scenes and chapters in the editing room during the production of the animation. Many of the ‘choices’ were born during the actual process. I guess that’s why the film had virtually no dialogue. It was created and narrated from the poetic power of images.

Were there any limitations you encountered that helped define the style of the film?

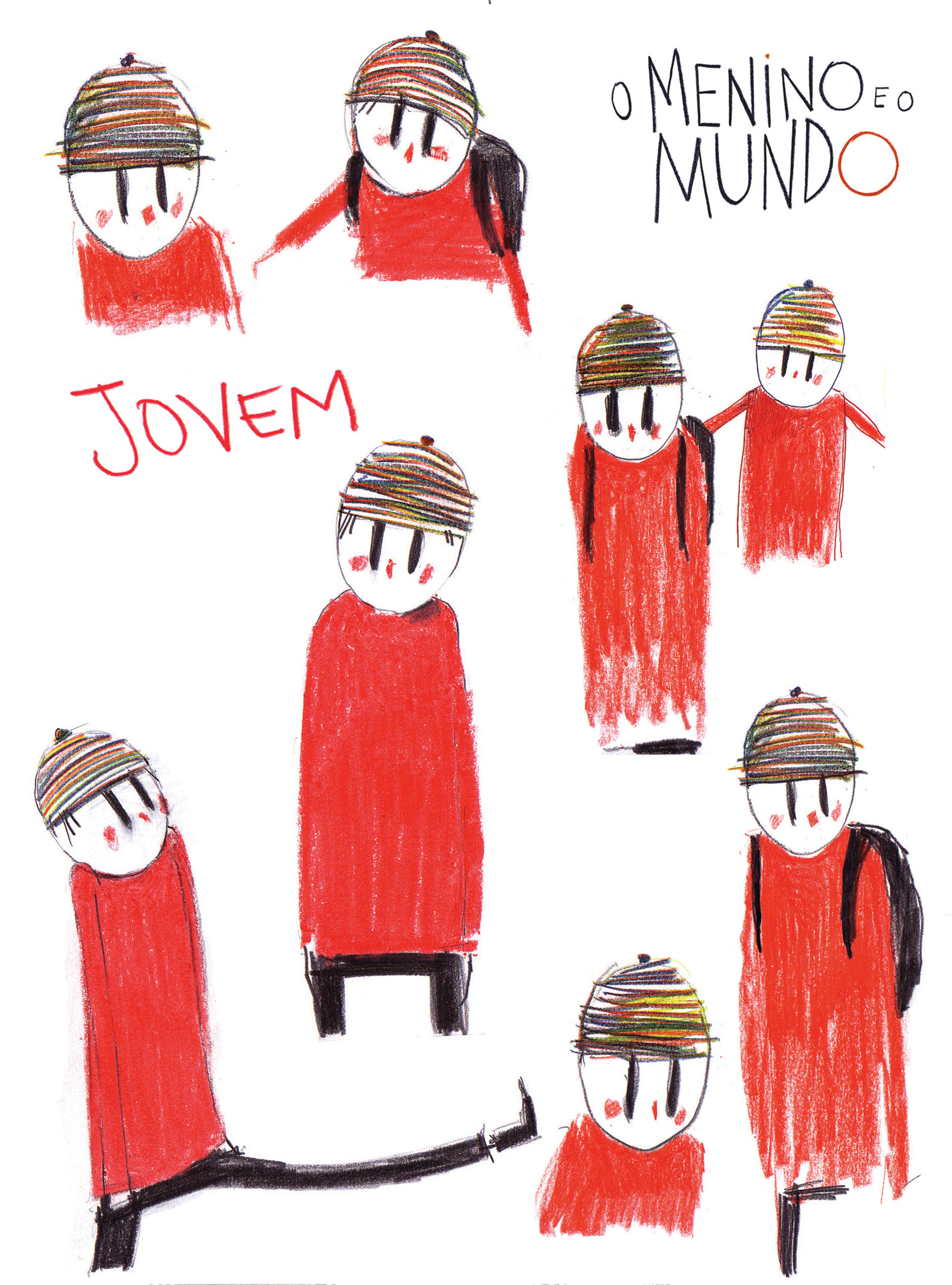

The style of the film wasn’t defined by any limitations, except for the universe of the child. We let that open up in front of us and decided to be guided by the boy character. We also tried to create graphics, conditions, and techniques that would encourage the power of freedom—to express ourselves like children do.

Was there any part of the final product that you were unsatisfied with?

It’s not unusual for artists to finish their jobs unsatisfied with the final result. It’s always possible to improve many different aspects of any project. It’s good to long for that. But an artist also needs a moment when they can be satisfied. The work of an artist is an eternal search for something. I think that’s the exercise of art. The search for a style becomes a great trial in the sense of self-knowledge.

For the first time in my life I was very satisfied with the final result of a job. Boy and the World brought me much relief in this regard.

You draw music in this film. It is vital to the narrative and a really strong visual aspect. Can you explain a bit about how this developed and why you wanted the music to be seen and not only heard?

I discovered the boy character in a scrawl that I had done in a notebook for another project, an animated documentary which was named Canto Latino. It was intended as a glance into the history of the formation of the Latin countries. It was a project with huge political, social, and economic dimensions. I decided to put that documentary aside when I found the boy drawing.

I still wanted to discover that history, but within the universe of the boy. I thought the boy could be separated from everybody else, excluded, to the point of being a special boy. He could be a special boy who would see the music and lead us all to another point of view. It turns out he also led us to the completion of the film itself.

I read that you have been influenced by the René Laloux’s 1973 film Fantastic Planet. What do you think makes an animation “good”? What appeals to you when you watching something like Fantastic Planet?

For me the best part of any animation is the possibility to transport us to another world where the fable has a very strong power. The fable pulls us away from reality, and at the same time brings us closer. It has the possibility to let us look at our world, and our lives through another lens, to better see it.

There are other films like this, which enchant us by making us look differently and they transform us. Years can pass by and they will be still stuck on us. They become a part of us.

See more of Alê Abreu’s work on his portfolio.

Header image via