In Pippin Barr’s latest computer game, it is as if you were doing work, the designer recreates the mind-numbing experience of doing boring, rote tasks on an office computer. As more and more jobs are lost to automation, Barr explores the possibility that, in a post-digital future, “work” could become something people enjoy and crave. And maybe this future has already arrived. The clicky browser game raise questions about the supposed divide between work and play, as well as between art and games.

Barr’s interest in making games began six years ago, when he was assigned to teach an experimental game design course at the IT University of Copenhagen. Now, he likes to make “about ten games a year.” The games are usually free and don’t require a download. They might look pretty simple, but push “start” on any one of them, and you’ll stumble into curious explorations of digital space and time.

His games are not games in the traditional sense of the word—that is, you cannot usually “win” a game by Barr. Instead, his games are thought-provoking, sometimes confounding, performance pieces, in which the player is just as much participant as they are viewer.

In one of Barr’s best-known works, The Artist is Present, the player enters the Museum of Modern Art and gets in line to witness the Marina Abramović performance piece of the same name. It is perhaps Barr’s most realistic game—gameplay consists of waiting in line for many hours before you can sit with Abramović. Other art-inspired Barr games draw on the installation works of Donald Judd e Gregor Schneider to raise questions about navigating digital space.

We got in touch with Barr to find out more about his wide-ranging work, collaborating with Marina Abramović, the creative abilities of computers, and why he created a game that will take 1,000 years to finish.

Wow, computers are so amazing. They can do all of this stuff. I am so pathetic as a human.

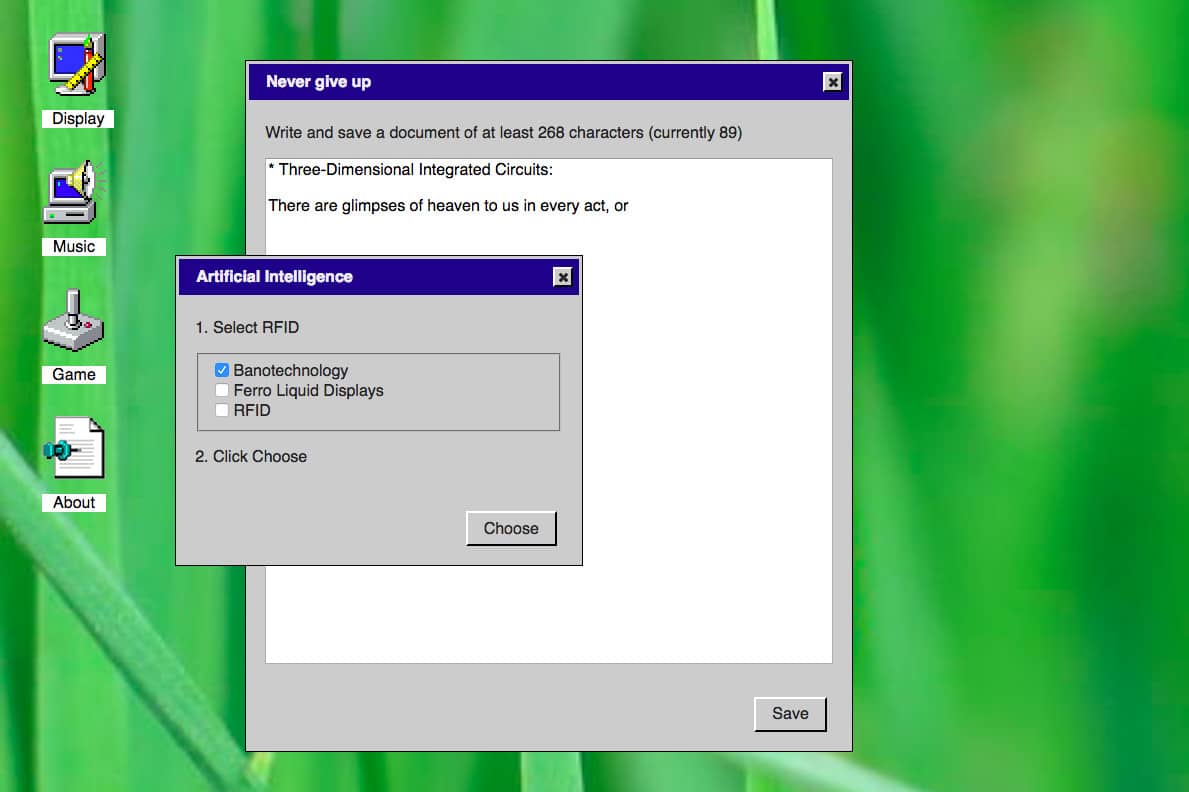

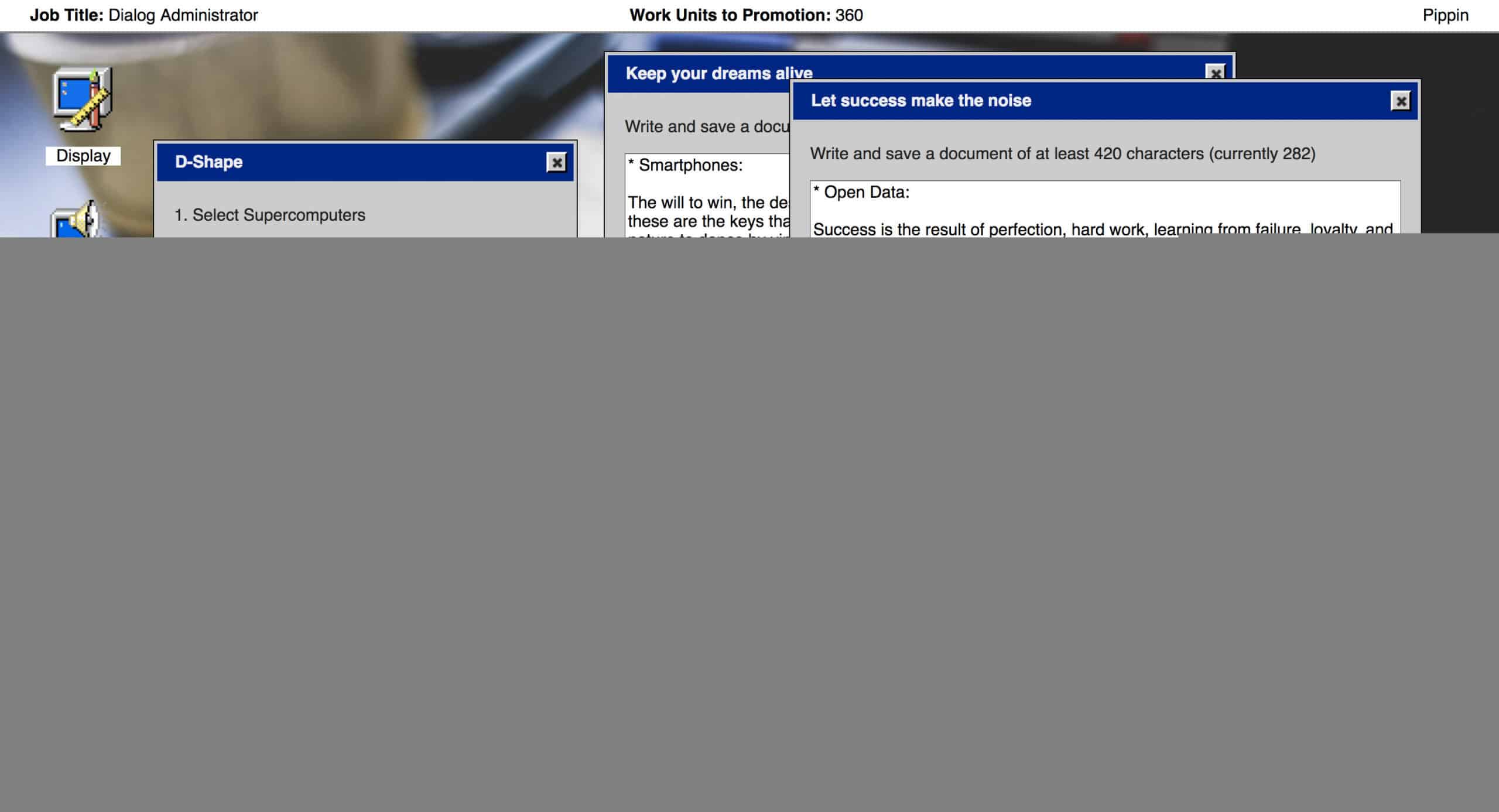

Screenshot from it is as if you were doing work.

Format: In writing about your games, you’ve mentioned this tension between the idea that algorithms can do everything, creating solutions to things that we can’t solve—but then technology is also vulnerable to obsolescence. There’s a tension where computers seem very fragile, but also all-powerful. Could you talk more about this?

Pippin Barr: Yeah, I like that tension. I’ve worked with that in a few games. A game a couple of years ago, called Best Chess, follows a similar kind of trajectory. In that case, the player makes the first move, as white, in a game of chess, and then the computer, playing as black, starts playing to solve the entire game. The algorithm to do that is not very complicated if you’re not worried about how long it’s going to take. There’s a fairly straightforward way of solving chess by just looking at every single possible game that could ever be played and then working out what the best sequence of moves would be.

So your computer starts doing that process, which seems kind of terrifying, you know, ‘Oh my god, it can solve chess!’ And in some sense it can. But the flipside of that is that it would take—not an infinite amount of time, obviously, but so much time that the computer itself would have disintegrated long before it would actually solve the game of chess.

There’s that cycling of, ‘Wow, computers are so amazing. They can do all of this stuff. I am so pathetic as a human.’ But then there’s also this idea that computers are very vulnerable, and prone to disasters of their own. They’re not so different from us in terms of ultimately having a physical existence, and being subject to similar issues of entropy, and so on, just like we are.

Chess games on the computer are weird, because presumably the computer can always beat you, but I guess it’s engineered to let you win sometimes.

Post-Deep Blue beating Kasparov at chess, I guess there’s now some sense in which technically there’s no human who could ever beat the best computer at chess anymore. Although I think they did some experiments where it turned out that a human working with the computer chess algorithm was still better than just a computer on its own. So there’s some minor hope for humanity there. But obviously computers are going to be better than us in the near future, if people keep working on it.

But I like the realization that computers are tying one hand behind their back and hopping around on one foot. It’s obvious they could destroy us if they actually wanted to, or were programmed to, but they have to be programmed to make us feel as though it’s a fair match-up.

I made a game ages ago called ZORBA, which was a dancing game that ignores that rule. The computer opponent in that game can do all of the dancing perfectly because it’s a computer and it doesn’t need to accidentally screw up a dance step— like Dance Dance Revolution on your keyboard. As a human you can’t keep up with it, because it’s much, much too difficult for a human to hit the keys fast enough and to register what’s going on. Being a computer, it doesn’t pretend that you are as good as it is or anything. It just destroys you every single time.

Being a computer, it doesn’t pretend that you are as good as it is or anything. It just destroys you every single time.

I think there’s a sense that people in artistic fields are safe from this, because it’s going to take a long time to teach computers how to write poetry or how to paint. But I don’t know if that’s true. Do you think computers will become able to algorithmically generate games that are really fun to play?

I would imagine that the way that we would value computer-written poetry would be different from how we value human-written poetry. Because human poetry comes from human experience, and it’s expressing something about a real person. A computer could put together the same set of words that are all beautifully balanced and have internal rhyming schemes and so on, but if you knew it was by a computer I think you would value it very differently than if it was by a human. I think you could be fooled, but I think if you knew it was by a computer it would feel different.

With a video game I’m much less sure. At least, for most consumer video games that are valid entertainment, I don’t know if people would care if those came from a human invention. So long as the game had a cool story where cool stuff happens, I think that people would probably be just as happy if a computer could generate that for them, or if a human team worked on it.

I think there are media where computers will be able to do these things, and then there’s the last bastion of real art, or whatever the hell that is, where maybe computers are always going to struggle to be taken seriously.

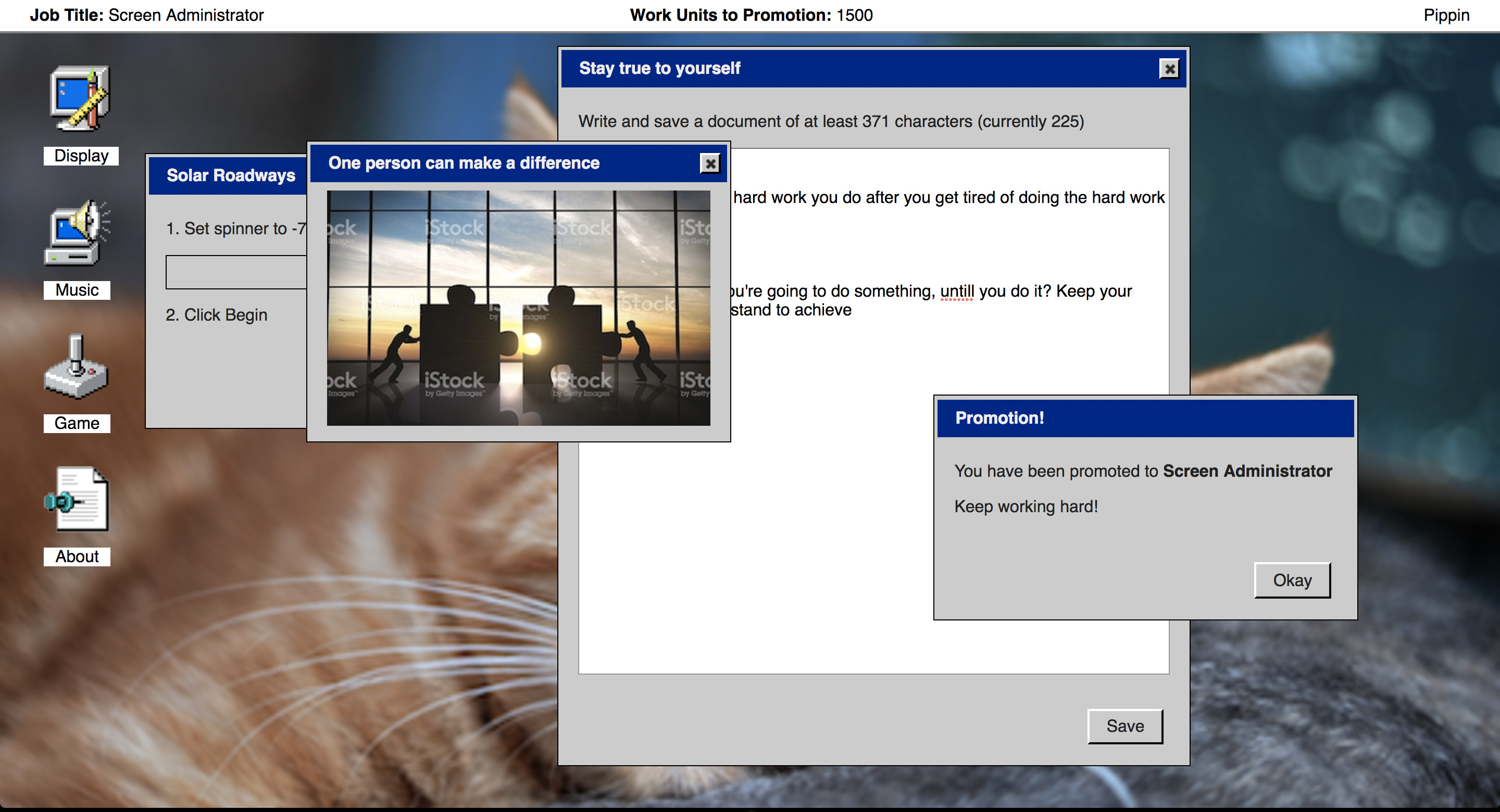

Screenshot from it is as if you were doing work.

I played it is as if you were doing work a little bit and it seems so boring and it does feel like you’re doing real work. But then I think a lot of games are like that. Clicking things repetitively, pressing buttons; what’s the difference?

It’s funny, we see work and play as being very, very different. But contemporary video games, if you start thinking about them, they are very productivity oriented and very much about doing the right thing over and over and over again in a production line way. Although there’s a lot of creativity in certain kinds of games, a lot of it does come down to doing similar things to what you may do in an office job.

Then there are cases where games literally become work, like when people are farming gold and resources in games like World of Warcraft. And work is a big part of games like Farmville, Minecraft, The Sims…

Clearly doing effective work is something that we really crave, even in our leisure time, because I guess in our real jobs often we don’t feel very effective and nobody ever tells us, ‘Oh, you did a really good job, or ‘You wrote an 80% good article.’ It’s never quite enough for us to feel secure. Whereas in video games a lot of the time what we want is that sense of productivity. We can repeatedly do the right thing and be rewarded over and over again for it.

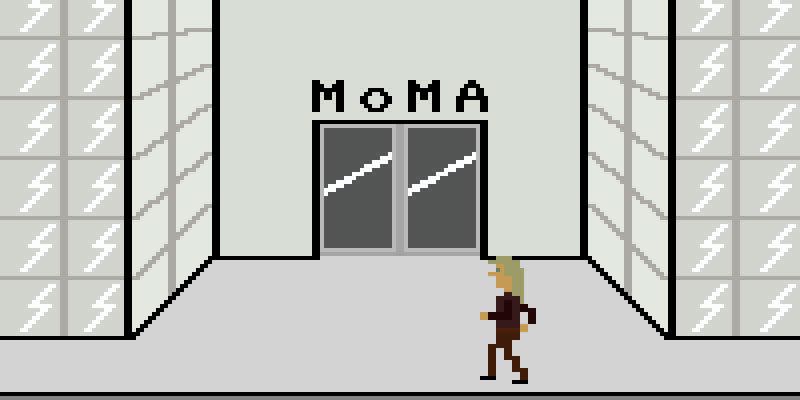

Screenshots from The Artist is Present.

I loved your game The Artist is Present. How did you come to work with Marina Abramović?

Roughly in the way you might expect. I made the game, The Artist is Present, while I was teaching a course about experimental game design. I was telling my students about the forms of experimental art in different genres, which included Marina Abramović. Researching The Artist is Present, I just thought it would be funny to have a game version of it. It’s the stupidest thing that you could possibly make a game about.

It got some attention out in the world because it was timely and people found also found it funny. There weren’t many games of that nature, at the time especially. Marina ran into the game at some point, and she played it, which was great. Apparently she had gone into the queue to try and sit with herself—which is a wonderful image—but then she’d gone off to make herself some dinner or something and she got kicked out of the queue. So she never made it through, but she did try, which is funny. It’s great, too, that this endurance artist didn’t have the patience to sit with herself.

It’s great, too, that this endurance artist didn’t have the patience to sit with herself.

But she liked it. She thought it was funny. When she was doing a Kickstarter for the Marina Abramović Institute up in Hudson, New York, she got in touch to ask if I would be interested in collaborating with her on a game thing that could be part of the Kickstarter. I jumped at it, because she is Marina Abramović, and I was interested to see what it would be like to work with her—and whether I could maintain my own identity in the face of such a strong personality, because she’s pretty mesmerising as a human.

We worked on a digital version of her institute, which was a fascinating thing to, and then also another little set of versions of the Abramović method. She has all these exercises that she gets people to do and I turned them into game versions, which is sort of delightfully perverse because all of her stuff is about how you are physically, and where you are. Traditionally we think of the digital as wiping all of that stuff away. You’re nowhere, and you don’t have a body, and so on. So it was really, really interesting to make those games. I got to meet her in Toronto and look into those eyes. It was a fun experience.

Screenshot from The Artist is Present.

What was she like to work with? Was she intimidating?

She was really great, actually. She wasn’t territorial at all about her work and how I wanted to interpret it. She was interested in my rationale for doing things, the ways that I thought were interesting for me, personally. Going into it, I certainly thought she was just going to lay down the law about what I was allowed to do, but it turned out that she was very, very open and supportive of reinterpreting her work in this new way.

In the game The Artist is Present, does the character ever get to the front? I started it but I didn’t have the endurance.

Yeah. It does take a really long time. Not very many people have made it to the front. When I did it, it took five hours, so it’s pretty arduous. But you can totally make it to the front. I’m always a little bit sad when people don’t trust me enough to believe that there is an outcome.

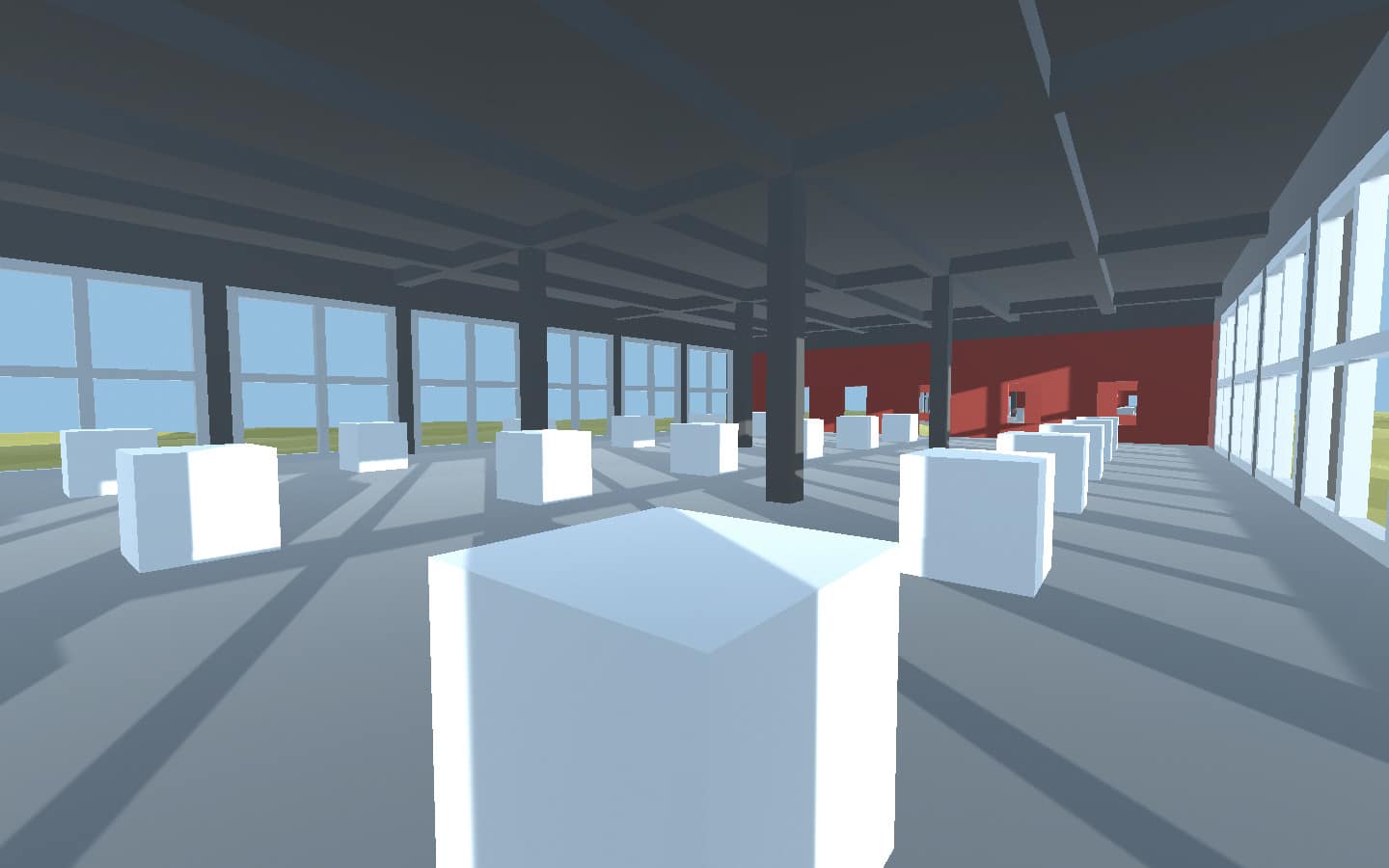

I made another game like that, the game v r 2 where there are objects hidden inside cubes in a 3D world. Again people would ask me, ‘Are those things really in there, or are you just fucking with us?’ That’s not how I do things. The things are definitely inside the cubes. You can definitely get to sit with Marina Abramović in the game. I’m not interested in that kind of trickery. It’s always legit.

Donald Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum (1982-1986) and screenshot from v r 2 (2016).

Could you tell me more about the v r games?

V r 2 e v r 3 are structurally based on Donald Judd’s 100 untitled works in mill aluminum in terms of their layout, and the minimalist sculpture and what small variations can do in the context of sculpture.

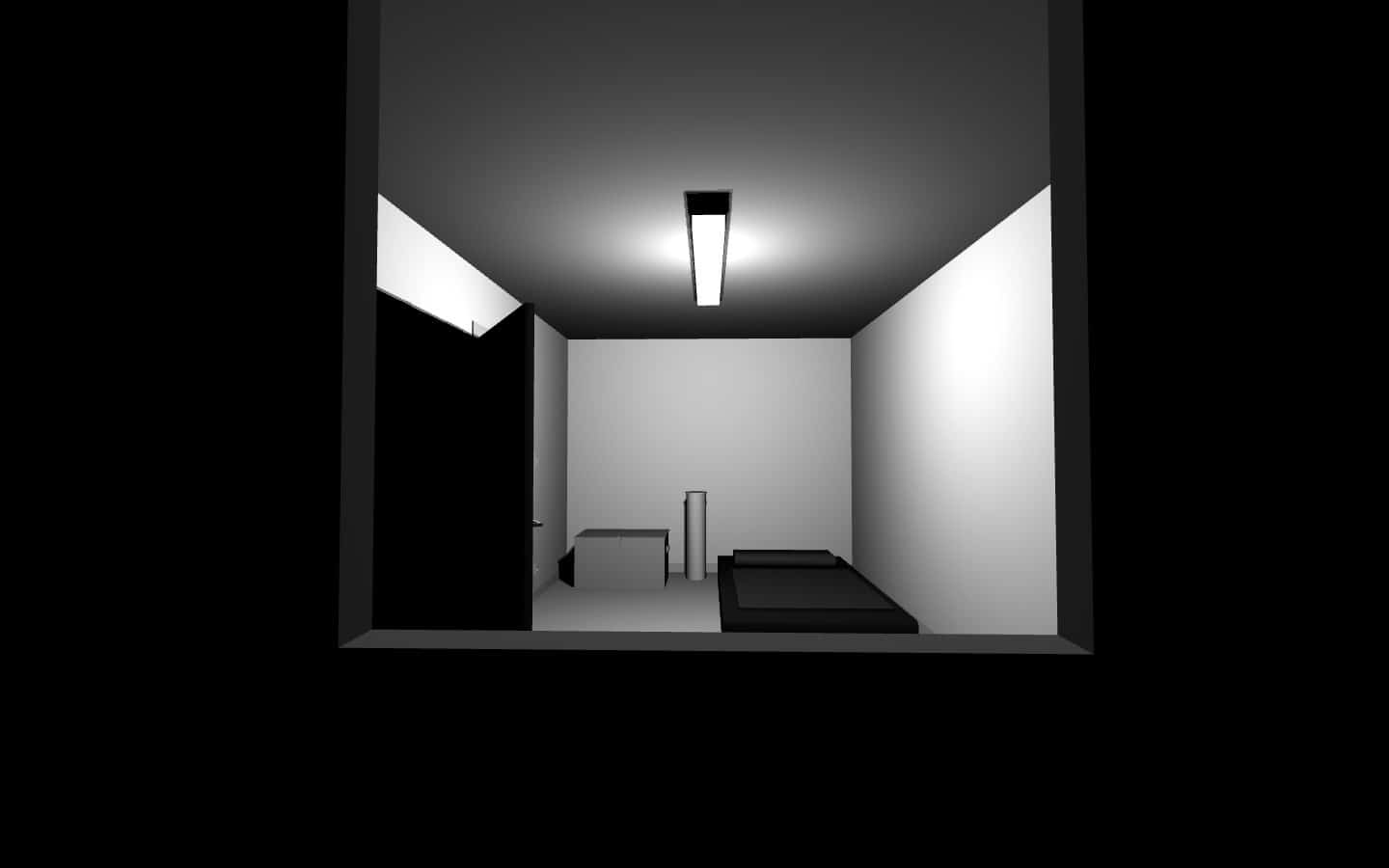

But v r 1 e v r 2 are also based on the work of an artist called Gregor Schneider, who is mind-blowingly interesting. He has this house that was given to him, I think by his father, which is kind of abandoned because it’s too close to a lead mine. Since he was 16, he’s been remodeling the interior of that house in these creepy ways; recreating the same room somewhere else in the house, making rooms that rotate, making walls that sit in front of other walls. His work is amazing in terms of architecture.

V r 1 was about his most famous room, that he’s recreated a lot of times in different contexts—and he recreates it physically with this incredible attention to detail, down to a scuff that’s on the wall. He’ll make sure that that scuff is in the recreation as well. V r 1 is about recreating that room in a virtual space. It’s so easy to duplicate things in a virtual world. You can literally copy and paste it and you’ll have the same thing, so duplication is interesting.

Schneider also has this interest in hiding objects inside walls. You’ll have this completely empty room, but he’s embedded a stone inside one of the walls. You can’t see it, and I think with a lot of them, you don’t even know that the stone’s there. It doesn’t tell you that it’s in the wall. He believes that there’s some influence that the stone being there has on your experience of the room, which is a really interesting metaphysical question. V r 2 is about that same idea. You can’t see any of these things, because they’re inside these cubes, but they’re still technically there. But if you can’t see them, especially in a virtual setting, are they really there? What does it mean for an object to be there if you can’t perceive it?

Gregor Schneider’s Totes Haus u r (1985), and screenshot from v r 1 (2016).

There’s a similar question when it comes to the duration of the games. if people played The Artist is Present and no one ever bothered to finish it, would the performance even exist? If Marina Abramović did the performance and no one came, would it matter?

If Marina sat there and nobody came, I think she would say that the performance didn’t happen, because she thought of the performance as being that moment of sitting with the person and communicating through just looking at each other.

Whether or not the ending can be said to be present in the game is a good question. I made these games that were of gradually increasing duration to explore—so towards the end, there’s a game that takes 1,000 years to finish. It literally takes 1,000 years. So obviously neither you nor I is ever going to see the ending. It’s not possible for us to live for 1,000 years, and it would in fact be very, very difficult for anybody to run the game for 1,000 years without their computer collapsing at some point. But being the person who wrote the game and tested it, I know that the ending is in the game. It’s in the code, and it will be triggered after 1,000 years. It’s just that nobody’s ever going to see that. That’s weird.

There’s a game that takes 1,000 years to finish. It literally takes 1,000 years. So obviously neither you nor I is ever going to see the ending…But being the person who wrote the game and tested it, I know that the ending is in the game.

Maybe we want to think that computers can live forever and outlast everyone. But actually their lifespan is very short.

Yeah. We treat them like they’re not fragile a lot of the time, even against all evidence as they continuously break down and their screens crap out and the keys die. But we never really treat them like agents that have vulnerabilities and injuries.

I’m interested in the aesthetic of a lot of these games, because they have this retro look to them. Why did you choose that style?

There’s a few different reasons, and the main one is it’s really hard to make good graphics without spending a huge amount of time working on them. Because I’m generally more interested in ideas, it doesn’t seem worth it to me to devote a huge amount of attention to realistic or better graphical representation. But then some of it is about referring to schools of game design from the past. We’ve moved so far beyond, say, the Atari, which was the ‘70s or something. But we don’t really think about the kinds of designs that were in play back then.

In some ways you could say design has just gotten better and therefore it’s not like that anymore, but it’s also just the technology advances relentlessly to the point where we don’t spend much time exploring the possible design space with a particular technology before we’re already hurrying to do something else.

Mais sobre jogos:

I Designed The Oregon Trail, You Have Died of Dysentery

Série de fotos: A cultura de videogame da Nigéria

7 Video Games Designed For Designers