Le concept de Nuage de pétales est venu à Sarah Meyohas dans un rêve de roses et de pixels. Un programme informatique pourrait-il être entraîné à créer des pétales de roses numériques plus ou moins indiscernables des vrais pétales ?

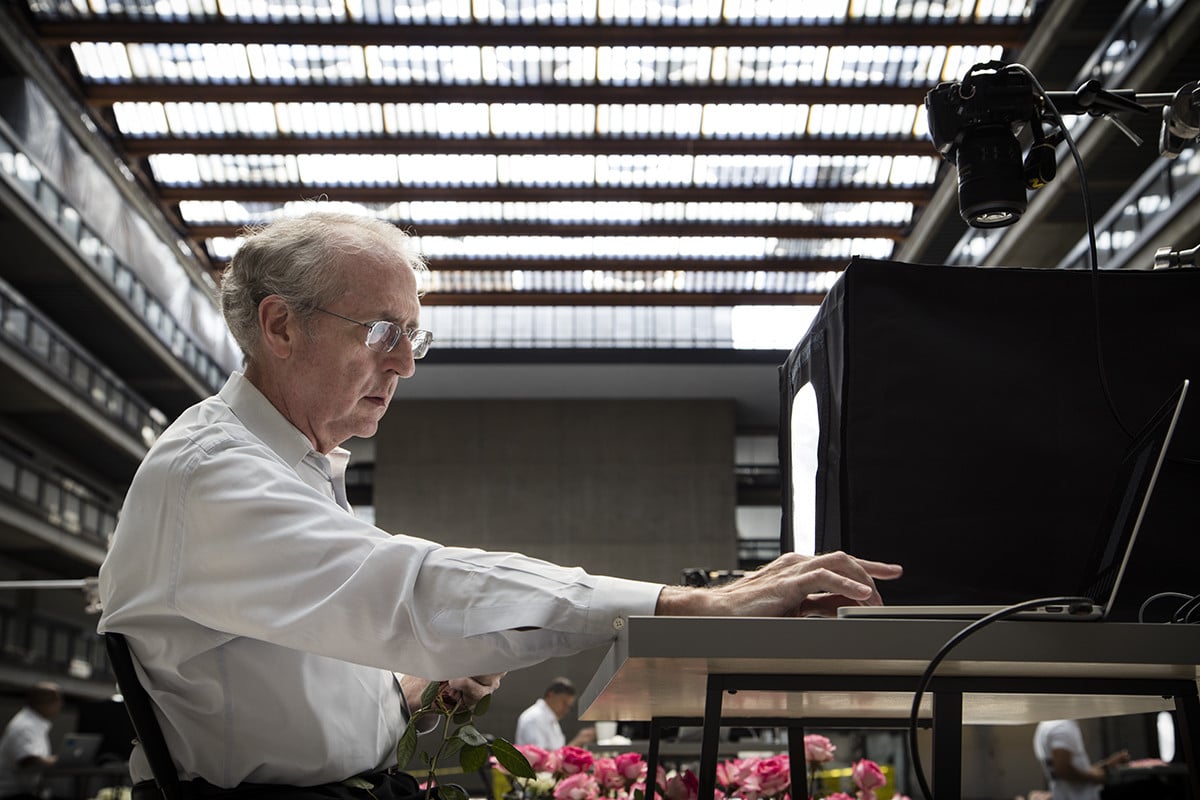

Avec l'aide d'un réseau accusatoire génératifElle s'est lancée dans un projet artistique de grande envergure qui remet en question la perception qu'a le spectateur des objets numériques et organiques. Dans une installation de recherche abandonnée à l'extérieur de Manhattan, elle a engagé 16 personnes pour photographier 10 000 roses fraîches. Les travailleurs devaient sélectionner dix pétales de chaque rose qu'ils jugeaient les plus beaux. Ce processus s'est déroulé sur une période de quatre jours, et Meyohas a tout filmé.

Elle a également enregistré le processus de création des pétales numériques à partir des images des pétales réels. Le résultat, un court métrage analogique, est un film autonome tout autant qu'une documentation sur une performance. Nuage de pétales projeté à Régence indépendante à Bruxelles cet été, et le projet est également exposé à l'exposition Red Bulls Art New York du 12 octobre au 10 décembre 2017.

"J'aurais pu truquer une grande partie du film", déclare Mme Meyohas sur Skype, depuis son bureau éponyme de l'Upper East Side. galeriequi lui sert d'appartement. "Les travailleurs auraient pu se contenter d'un après-midi de tournage, au lieu de quatre jours entiers. Je n'ai pas eu à collecter 100 000 photos, ni à réaliser un réseau génératif contradictoire. J'aurais pu faire semblant avec de l'animation. Mais c'est réel.

Meyohas explique que le processus de photographie des roses a été inspiré par les éléments suivants Google BooksGoogle tente d'archiver le plus grand nombre possible de documents imprimés par le biais d'images numérisées. "C'est le même processus. Mais au lieu d'ouvrir une fleur, vous ouvrez le livre et vous scannez la page".

Malgré son caractère documentaire, le film de Meyohas Nuage de pétales est onirique, très troublante et finit par créer plus de questions qu'elle n'apporte de réponses. Elle déclare : "Créer des pétales qui n'ont jamais existé, c'est cette tentative de créer la nature. Utiliser la technologie pour s'émanciper de la biologie. Quelles en sont les répercussions ?".

La pratique artistique de Mme Meyohas couvre un large éventail allant de la performance à la photographie. Elle est peut-être plus connue pour son projet numérique de 2015 BitchcoinElle a créé une monnaie numérique adossée à la valeur de ses propres œuvres d'art. "Il s'agit d'un pari sur Sarah Meyohas qui n'a pas d'expiration. Bitchcoin indique sur son site web. Grâce à son diplôme d'économie, elle a également exploré la sémiotique de la finance dans les domaines suivants Performance des actions, une pièce qui a manipulé le marché boursier et a représenté les résultats en direct sur la toile. Nuage de pétales rassemble les intérêts disparates de Meyohas - corps, économie, technologie numérique.

Mais pourquoi les roses ? "La rose, explique M. Meyohas, est devenue un symbole de beauté et d'amour, et c'est aussi une fleur très commerciale et facile à cultiver. C'est une fleur qui peut pousser en Afrique, en Amérique du Sud et en Europe, et nous l'avons sélectionnée pour qu'elle pousse dans des tonnes de groupes de couleurs différents.

Les roses, qui ont des millions d'années, sont cultivées dans les jardins depuis environ 5 000 ans. Dans la Rome antique, la rose représentait la déesse Vénus, et dans les sociétés chrétiennes primitives, les roses symbolisaient la Vierge Marie. Elle était également la fleur nationale de l'Angleterre des Tudor. Malgré ses connotations romantiques, La rose a une longue histoire comme le symbole de certaines des forces les plus puissantes de la civilisation. C'est une fleur de contrastes : amour et commerce, religion et gouvernement, pixels et pétales.

Les discussions sur la vie numérique sont toujours truffées de dichotomies : IRL contre online, amitiés contre Facebook, journalisme contre fake news. La technologie numérique évolue si rapidement qu'il peut sembler impossible de suivre les différentes façons dont elle médiatise nos vies. Nous créons des parallèles comme ceux-ci pour préserver le fantasme d'une réalité qui existe en dehors de l'internet, non altérée par les technologies numériques, un monde pur exempt des dangers de Snapchat, des logiciels de reconnaissance faciale et des tweets des politiciens.

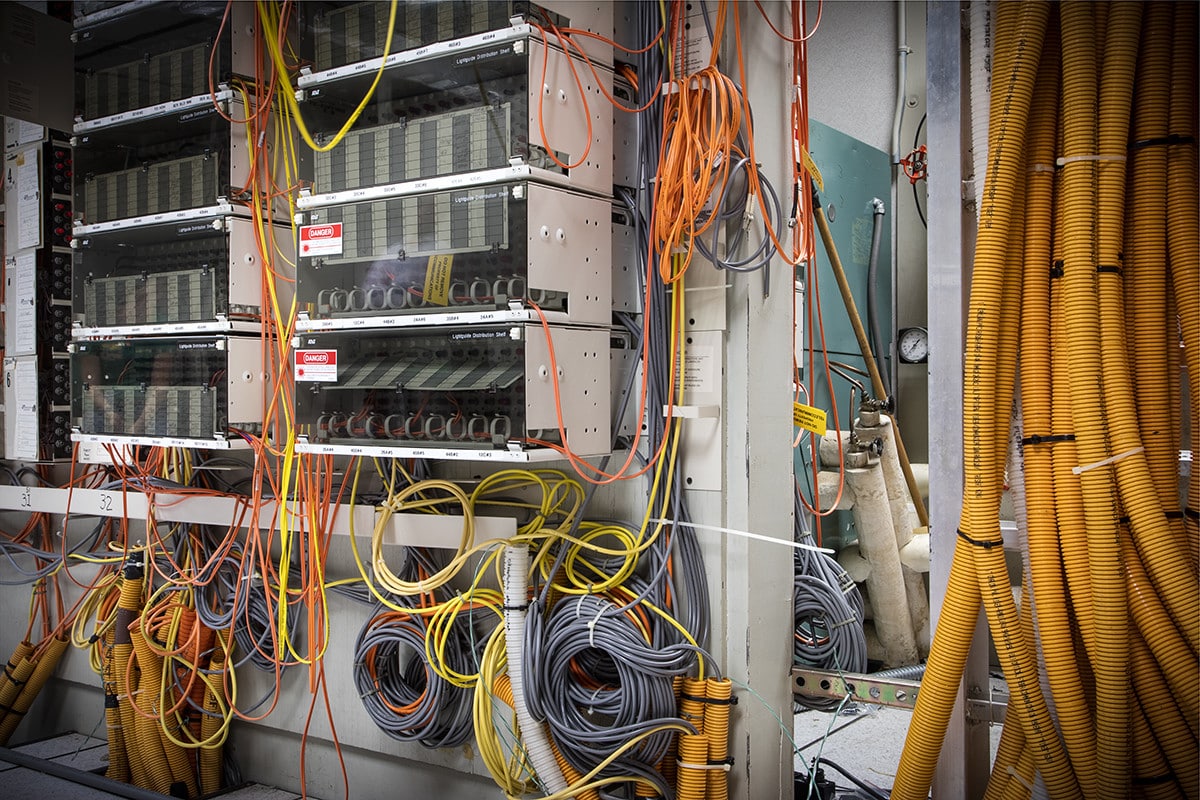

Avec Nuage de pétalesMeyohas remet en question cette idée, en brisant la frontière artificielle entre le numérique et le réel. Les pétales de rose générés par ordinateur dans son film ne sont pas moins réels que les araignées et les mouches qui planent devant la caméra - ou que le serpent qui fait également son apparition. Il s'agit d'un épais python jaune qui se faufile entre les fils électriques enchevêtrés de l'entrepôt abandonné aussi facilement que s'il s'agissait de lianes sur le sol d'une forêt. Le symbolisme biblique n'est pas un hasard. Tout comme le serpent dans le jardin d'Eden, le serpent de la vidéo perturbe ce qui semble être l'ordre naturel des choses. Nuage de pétales souligne que l'ordre naturel n'est déjà plus qu'un fantasme.

Meyohas indique que le projet a suscité des comparaisons avec le travail de Taryn Simonqui est connue pour ses archives soigneusement construites. Cependant, le processus d'archivage en Nuage de pétales est aléatoire, plus organique qu'organisée. Après tout, malgré sa nature numérique, l'objectif de l'apprentissage automatique est d'imiter les imperfections de la vie en dehors de l'écran. Contrairement aux archives de Simon, qui s'efforcent souvent d'imiter les imperfections de la vie à l'extérieur de l'écran. préserver un temps et un lieuL'archive de Meyohas est une forme de destruction.

"Les fleurs vont toutes mourir, elles ont été cueillies, elles ont été coupées", souligne-t-elle. "Tout cela est lié à la mort. Les vraies roses utilisées dans Nuage de pétales finira par se flétrir, et les images des pétales de roses numériques seront effacées, corrompues ou rendues illisibles par la marche en avant de la technologie numérique. Mais, imparfaitement archivées dans le film de Meyohas, on a l'impression qu'elles pourraient exister pour toujours.