Known both for her work as an activist and artist, Zoe Leonard was born in New York in 1961 and went on to become a pivotal figure in the city’s arts community. She works in photography, found objects and sculpture. Leonard has been a member of ACT UP, WAC, Gang, and Fierce Pussy. She’s worked to advocate for AIDS patients, women’s rights, the protections of black and gay identities, and a myriad of other causes. Her new show Survey, a mid-career exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art on view through June 10th, takes the viewer through her nuanced range of strategies that prioritize the human qualities of an urbanized world.

Often working with repetition, Leonard has a keen eye for recognizing the important materials that go unseen. She often uses overlooked objects to discuss overlooked issues. A major component of Leonard’s practice, which is based in photography, sculpture, and found objects, is surveying the world around her to locate objects and images for her work. In this way, she is primarily a collector, a powerful re-framer of images and artifacts. Leonard is not interested in objects solely for their formal aesthetics, but for their cultural residue and metaphorical capacity.

This exhibition at the Whitney asks visitors to consider own daily lives and experiences through an altered gaze. The installation You See I Am Here After All (2008), a collection of Niagara Falls postcards, represents an array of timelines and intersecting experiences. The cards are artifacts of personal, yet ubiquitous, moments. Collating the remnants of a nostalgic design, You See I Am Here After All points to the commodification of memory and the commonality of perspectives. Through repetition, what was once banal becomes a powerful, time-traveling object. In this work and throughout Survey, the objects Leonard presents or photographs have a magical quality; like talismans, they work to transport us to new narratives and multiple timelines.

In a 2018 discussion at The National Gallery of Art’s Diamonstein-Spielvogel Lecture Series, Leonard compared her work to that of a writer. She takes in the world, collects pieces of it, and hoards elements to edit, hone, and present at relevant later dates. This is the crux of what makes her work so powerful and at the same time marked by considered subtlety. Leonard is seeking to diversify assumptions about what art can and should be.

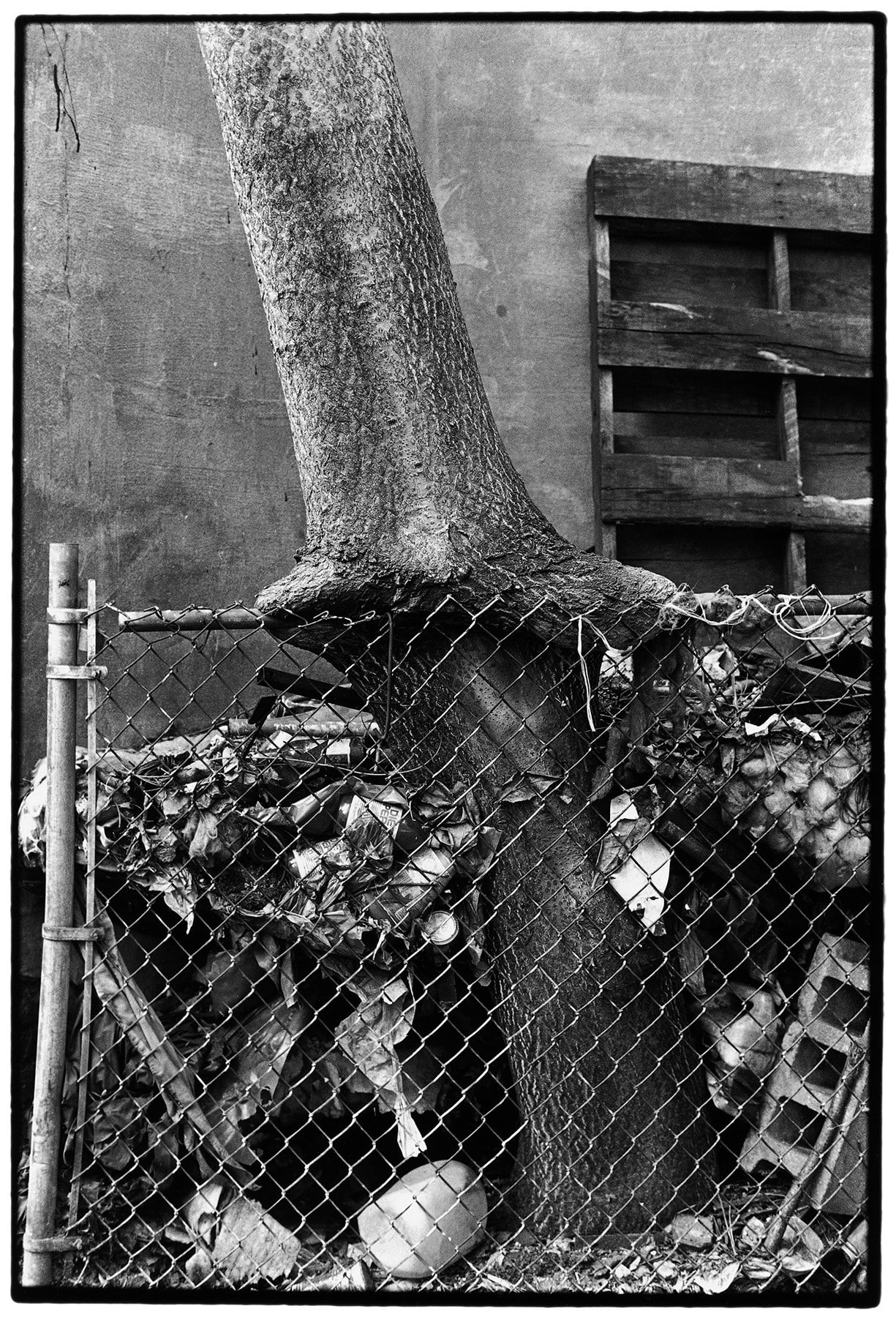

Tree + Fence, 6th St. (Close-up). 1998, printed 1999. Gelatin silver print on paper, 262 x 178 mm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

Seeing an original copy of Leonard’s well-known poem I want a president… is both exciting and poignant, a highlight of the exhibition. It didn’t stand front and center, but was framed under plexi, unassuming like all her works, beckoning for the viewer to come closer. The fading words produce a distinctly private, and human, moment within the institutional space of the Whitney.

I want a president… was originally written for Leonard’s friend Eileen Myles. Like Leonard, Myles’s work as a poet and novelist also uses a realist and pedestrian perspective as the basis for interweaving large issues of gender, race and class; Myles ran for president in 1992, an effort that was more activist performance than a serious endeavor. I want a president… is particularly resonant now, with Leonard’s call for a president who can relate to common experience feeling more crucial than ever considering the current state of American government. In the wake of the 2016 elections, Mykki Blanco offered a contemporary interpretation of the poem that helped introduce Leonard to a new generation.

Walking through the exhibition I was struck by the unexpected quietness of the series of black and white photographs most commonly titled as Tree and Fence. Unlike some of the bolder political works, these photographs are a slow burn, and speak to Leonard’s more poetic attitudes. This work depicts trees that have grown through, between, or become one with fences. Protruding through the metal that constrains them, these trees seem to take on a bodily form, a near-human sense of intent. Regarding this work, Leonard told the Tate:

“What I’ve always liked about photography is that it’s such a direct way of showing what’s on my mind. I see something. I show it to you. When I returned to New York, the tree outside my window attracted my attention in a whole new way. Once I had photographed it, I began to notice similar trees throughout the city … I was amazed by the way these trees grew in spite of their enclosures – bursting out of them or absorbing them. The pictures in the tree series synthesize my thoughts about struggle. People can’t help but anthropomorphize. I immediately identify with the tree. At first, these pictures may seem like melancholy images of confinement. But perhaps they’re also images of endurance. And symbiosis.”

The metamorphosing trees and fences of Tree and Fence bend, grow, morph, swell, intersect, slash, masticate, and blend. The way Leonard personifies objects is paramount to understanding how she records a subject. Recorded over a period of years in the 1990s and 2000s, the durational nature of Tree and Fence points to Leonard’s constantly moving eye, her visual collection of the world, and search for under-seen subjectivities.

TV Wheelbarrow, 2001, Dye transfer print, 50.8 × 40.6 cm. Collection of the New York Public Library.

In addition to the Tree and Fence series, Survey include a large number of small format street photographs which demonstrate how Leonard captures the little-examined intricacies of urban life. She examines and re-presents physical situations that are compositionally and colorfully comely, but also meaningful in where she shoots her lens. There’s no technical prowess emphasized in these works. But her work is constantly talking about the process of photography; this is summed up by a work that wasn’t included in Survey, the Camera Obscura series, in which she replicates the historic camera strategy to take images of the sun. Yet, even in Leonard’s sculptures, she is talking about the task of photography to hold on to memory, to present proof, and to reference. There’s no distinction in her work that makes it necessary to parse apart the history of photography and her poetic nature.

There is a sort of effortless quality to these photo works, yet they are part of a collection that took years to capture. Like all Leonard’s work, these images are the result of a constant surveying of the world, its perspectives and its objects. We can assume that this might include hundreds of other collections that may not have come to fruition yet, or may never fully form. Speaking to Molly Prentiss for Revista Interview, Leonard describes her photography as “tied to a very specific relationship with the material world.” For Leonard, photographing is “an act of observation, but it’s not an act of objective recording.”

In this way, she pursues the activity of her work with the medium of photography but with the outlook of a writer. She collects experiences to later employ with a body of work, a narrative she writes through the world in pictures.

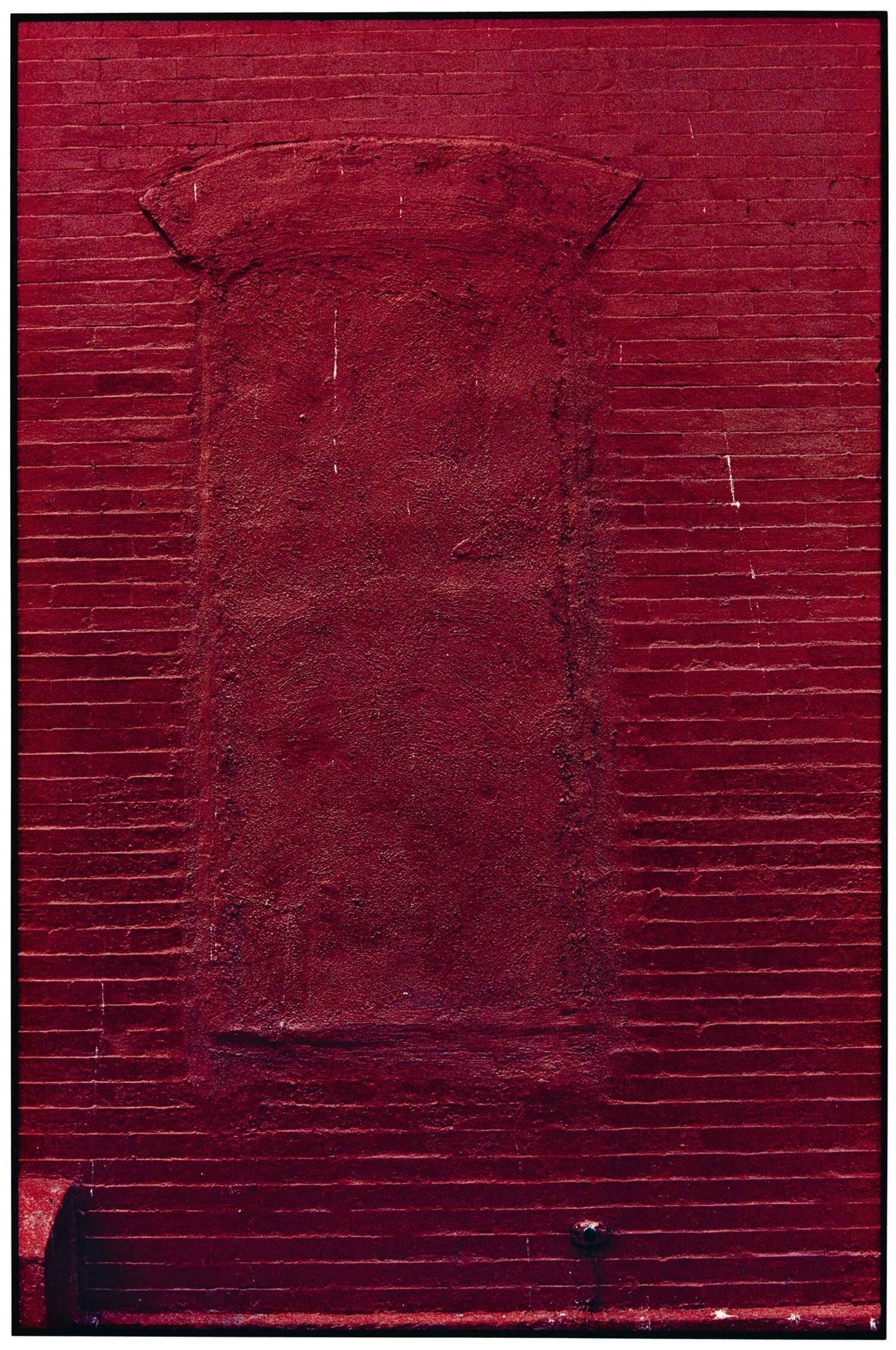

One of the most emotionally powerful pieces in the exhibition is Strange Fruit (1992-1997), titled after Billie Holiday’s haunting song. This work consists of amassed pieces of leathery, dried-out fruit peels sewn together in different configurations. Installed on the floor, these refuse-based sculptures recall a street covered in organic trash, or even bodies; Strange Fruit was made in reaction to the 1980s AIDS crisis. Many of the works in Survey are similarly emotionally charged. For example, two images of plastered-over windows, both untitled. These works reference photographic monochromes or shallow relief sculptures in form. However, in poetic content, they echo the same spirit of Strange Fruit, evoking residential loss and personal erasure.

Survey makes it clear that Leonard has found a way to let the world speak for her. It’s like she’s taken chalk and outlined these anthropomorphized metaphors in found situations. A plastered wall represents loss. Dried fruit shows the decay of the body. A tree becomes a trapped and contorted being. It’s not her authorship that is necessarily of value, but rather the details and meaning of something that was already beside us—a conceptual levelling out of time, class, and space. It’s Leonard’s position that creates the work, it’s really what’s on display. Her repetition and swivelling viewpoint projects, snipes, and dissects. Most importantly, she presents a framing of otherwise looked-over material in a pedestrian world.

Red Wall, 2001/2003. Dye transfer print, 75.4 x 52 cm. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

Cover image: Strange Fruit, 1992-97 (installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). Orange, banana, grapefruit, lemon, and avocado peels with thread, zippers, buttons, sinew, needles, plastic, wire, stickers, fabric, and trim wax, dimensions variable. Collection Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with funds contributed by the Dietrich Foundation and with the partial gift of the artist and the Paula Cooper Gallery. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.