El artista William Schaff necesita una calavera, una lata de Coca-Cola, cigarrillos e hilo de bordar para hacer diseños de portadas de discos de alt-country.

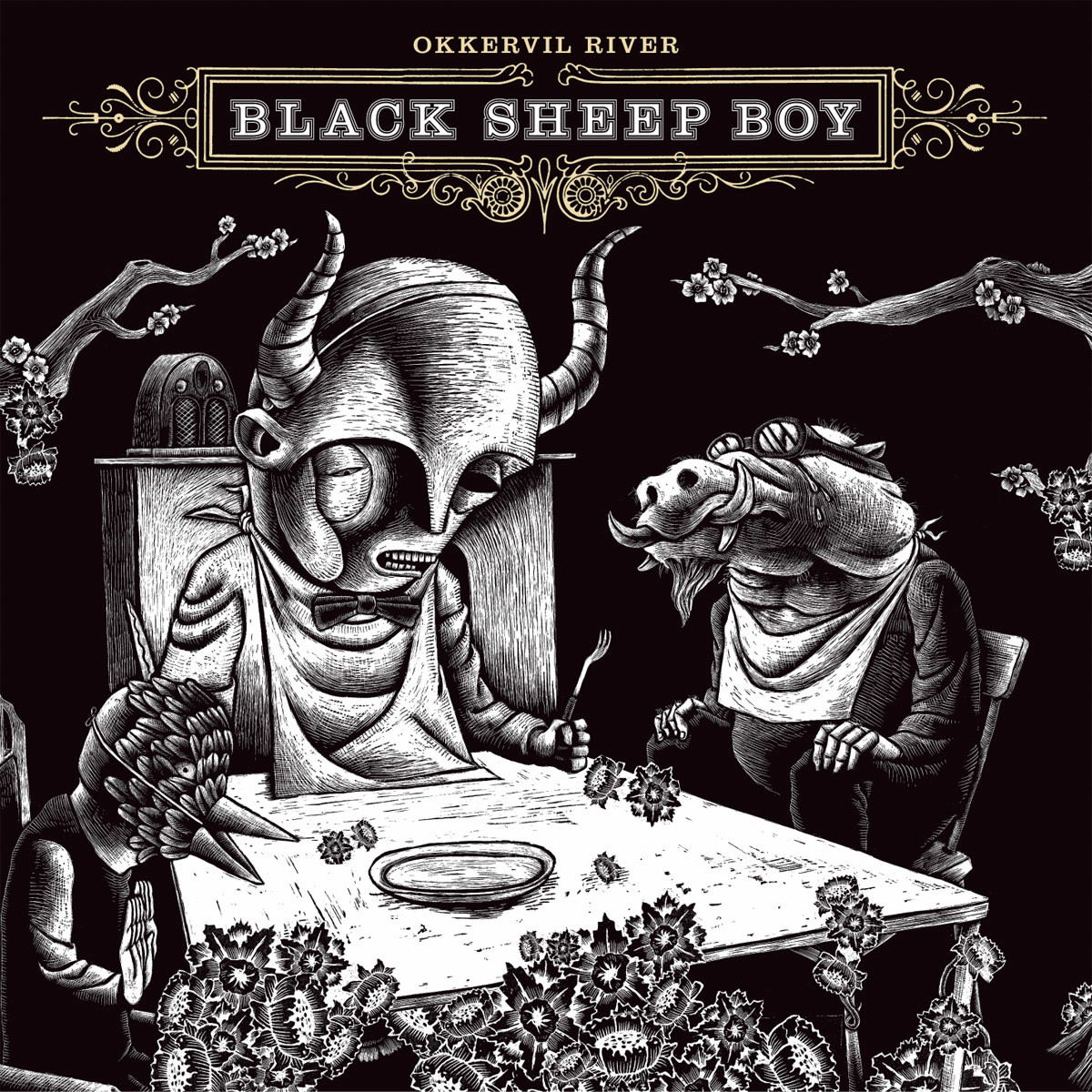

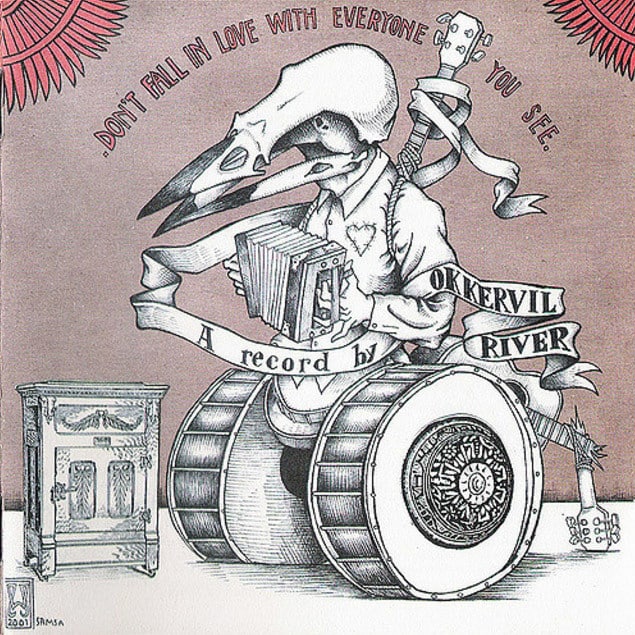

¡Si alguna vez has escuchado a los grupos Songs:Ohia, Okkervil River o Godspeed You! Black Emperor, es muy probable que te hayas topado con el trabajo del artista William Schaff en las portadas de sus discos.

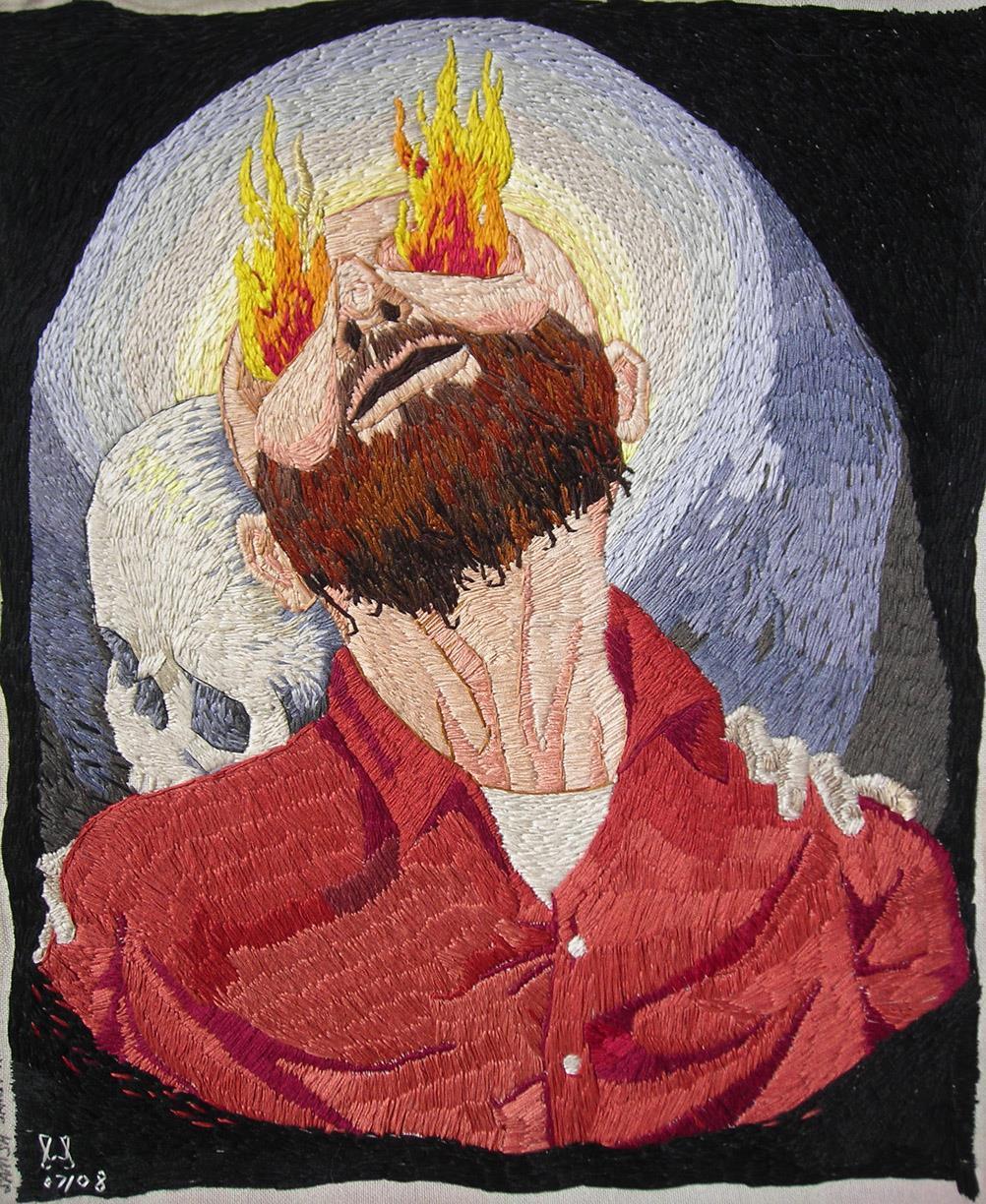

La prolífica producción de Schaff abarca desde recortes de madera hasta bordados e incluso naipes. Cada pieza conserva su toque distintivo, y todas parecen proceder de la misma especie de mundo espiritual. Ese mundo contiene innumerables calaveras y huesos, grotescos híbridos humano/animal, deformadas imágenes religiosas y palabras escritas, a menudo extraídas de letras de canciones de músicos con los que ha trabajado.

Aunque el término se utiliza a menudo en exceso o erróneamente, la descripción más adecuada del arte de Schaff es inquietante: es instantáneamente memorable, imposible de olvidar y propenso a abrir las compuertas del deseo de una reflexión más profunda sobre sus mensajes.

Schaff reside actualmente en Rhode Island, donde trabaja en su estudio, llamado Ejecución hipotecaria en Fort. El Fuerte debe su nombre a las numerosas veces que Schaff ha tenido que rescatarlo de una ejecución hipotecaria, lo que finalmente culminó en un Campaña Indiegogo no sólo para mantener las luces encendidas, sino para salvar su hogar y un lugar que ha seguido siendo una increíble incubadora de las artes -desde el arte visual a la música, pasando por los podcasts- en su comunidad. La campaña ha terminado, el Fuerte sigue abierto y Schaff tiene una página de donativos que le ayuda a seguir trabajando.

Las herramientas de Schaff incluyen, entre otras: calaveras (como inspiración y referencia), sellos (como parte de su programa de suscripción de arte por correo) y dinero, que entra en algunas de sus piezas, pero uno supondría que también ayuda mucho a obtener todas las demás herramientas.

Hablamos con Schaff sobre su arte, el uso de las redes sociales para seguir el progreso y por qué las imágenes de la muerte no son necesariamente morbosas.

¿Quién es usted y qué hace?

Me llamo William Schaff. Hago arte visual. Principalmente obras de arte en 2D, a veces en 3D.

¿Cuáles son las herramientas más importantes de tu oficio?

En última instancia, tendría que decir que es el lápiz y el bolígrafo. Mi formación fue como delineante, así que es con lo que me siento más cómodo. Pero la lista continúa a partir de ahí: Cuchillos X-Acto, hilo de bordar, agujas, tintas, pegamento, tijeras, fotocopias de mi trabajo para hacer collage, el ordenador para los correos electrónicos, el iphone para instagram, etcétera, etcétera.

Estás muy activo en Instagram. ¿Qué utilidad crees que tiene la aplicación para ti?

Publico para la gente que me sigue allí. Al principio era muy reticente a no unirme cuando salió, pero no se puede negar la importancia de las redes sociales para hacer posible este trabajo.

Así que, como ya tenía un Flickr y una cuenta Facebook cuenta, pensé que con Instagram pondría más fotos entre bastidores, algo que te mostrara un lado de las cosas que no verías si me siguieras en otro sitio.

Intento que siga siendo interesante para quienes tengan la amabilidad de interesarse y seguir el trabajo y su progreso.

Puede ayudarme a ver las etapas. También es simplemente ordenado. Nunca había documentado ese proceso tanto como ahora. Así que estoy viendo una faceta de mi trabajo que nunca había visto antes. También es divertido para mí.

¿Qué tipo de ambiente necesitas crear en tu estudio para poder trabajar?

Necesito que el entorno en el que me encuentro refleje mi trabajo de un modo u otro. Dedico mucho tiempo a crear un espacio de estudio que me inspire y refleje el trabajo que estoy haciendo.

Hay veces que trabajo fuera del estudio para cambiar de ritmo, y esas veces no es tan necesario tener un entorno así. Pero, en su mayor parte, existir en una manifestación física de la obra tiene más sentido para mí que no, a la hora de crear.

Las paredes están llenas de trabajos anteriores para que vea lo que he hecho bien y lo que he hecho mal en el pasado. Me rodean libros, accesorios y objetos efímeros, cosas a las que puedo recurrir en el momento por cualquier motivo.

Hay mucho morbo en tu obra. ¿Qué te atrae de las imágenes y temas relacionados con la muerte?

Siempre me estremezco un poco cuando oigo a la gente describir mi trabajo de ese modo. Webster's ofrece ésta como una de las definiciones de mórbido: "caracterizado por o que apela a un interés anormal y malsano por temas inquietantes y desagradables, especialmente la muerte y la enfermedad."

La muerte forma parte de la vida. No se trata de una comprensión tonta o simplificada de una etapa de nuestra vida biológica, sino de un hecho. Con ese hecho viene el efecto que la muerte tiene sobre nosotros y sobre todo/todos los que nos rodean. Impregna las cosas tanto como los rayos del sol y la luz de la luna. Reconocerlo y examinar esos efectos, a menudo ignorados, no me parece "malsano". De hecho, yo diría lo contrario.

En cuanto a lo que me atrae de esas imágenes, es el hecho mismo de lo entrelazadas que están y su efecto lo que me atrae. Veo eso tanto como veo el impacto de la vida. Intento mostrar ambas cosas en la obra.

Creo que la gente está tan programada para creer que la muerte es algo negativo, o lo incómodos que les hacen sus resultados, que ven mi voluntad de afrontarla y existir con ella como algo morboso. Siento que es importante.

Parece que el miedo lleva de las narices a mucha gente, y la muerte es algo a lo que la gente tiene mucho miedo. El propio miedo se convierte en una especie de muerte, en sentido metafórico. Así que intento mostrar eso de la misma manera que Norman Rockwell nos mostraba escenas de la vida cotidiana. Simplemente señalo dónde podría estar la muerte en relación con las personas de esas escenas.

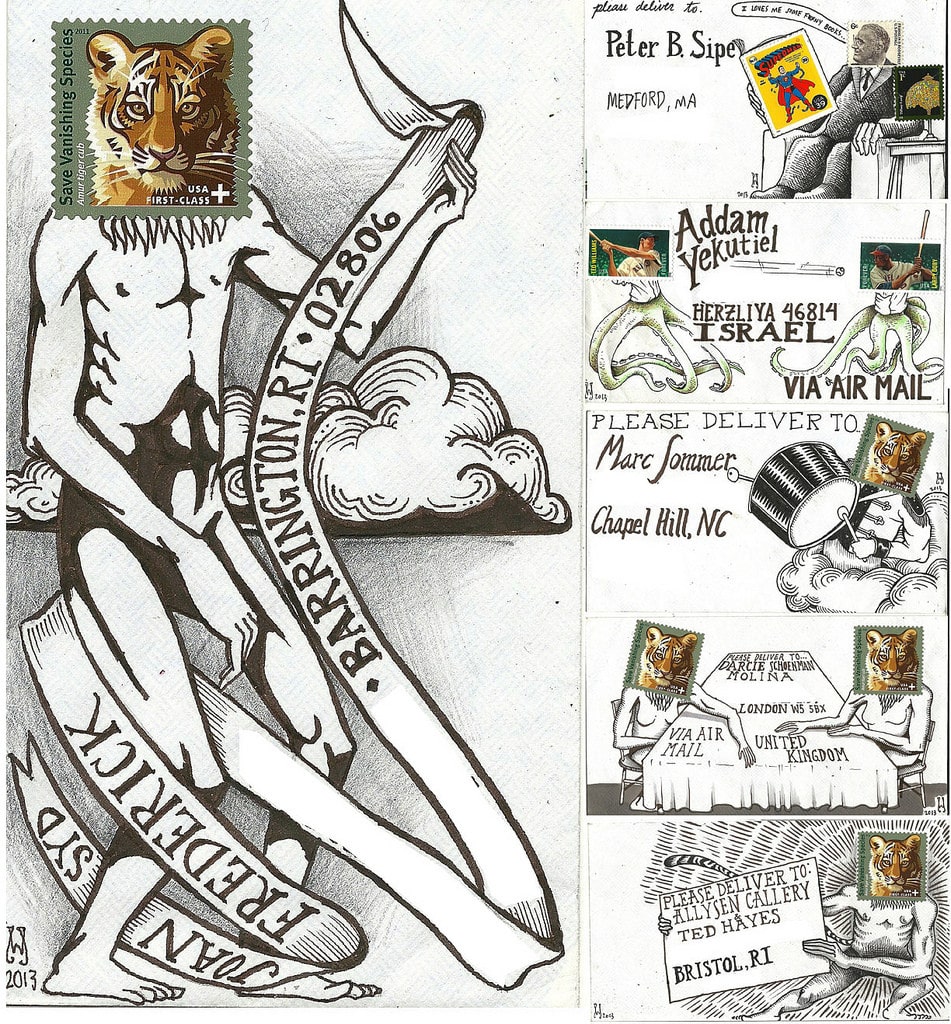

Tienes una serie de trabajos llamados "Arte postal" que incluye sobres de elaborado diseño. ¿Cuál es la historia de ese proyecto?

Empecé hace casi 20 años, cuando Internet era superlenta debido a los módems telefónicos. Esperaba a que se cargaran las páginas y un día me puse a dibujar en el sobre de una carta que iba a enviar a un amigo.

A lo largo de los años se ha convertido en algo que he intercambiado con la gente, u ofrecido una especie de suscripción, para ayudarme a costearme la vida como artista.

Me gusta ver cuál es la historia de la parte de la imagen del sello que no vemos, así que a veces hago que el sello forme parte de la imagen general. También utilizo esa parte del arte para ser un poco más tonta que en el resto de mi trabajo.

@williamschaff

William Schaff Cartera