Encontrarse cara a cara con un misil nuclear puede no ser la idea de diversión vacacional de la mayoría de la gente, pero hay exactamente dos lugares turísticos en Estados Unidos dedicados a esta oportunidad. El fotógrafo Adam Reynolds recorrió el Sitio Histórico Nacional del Misil Minuteman, en Dakota del Sur, y el Museo del Misil Titán de Arizona, para registrar en una serie fotográfica el extraño atractivo de los artefactos nucleares de la época de la Guerra Fría.

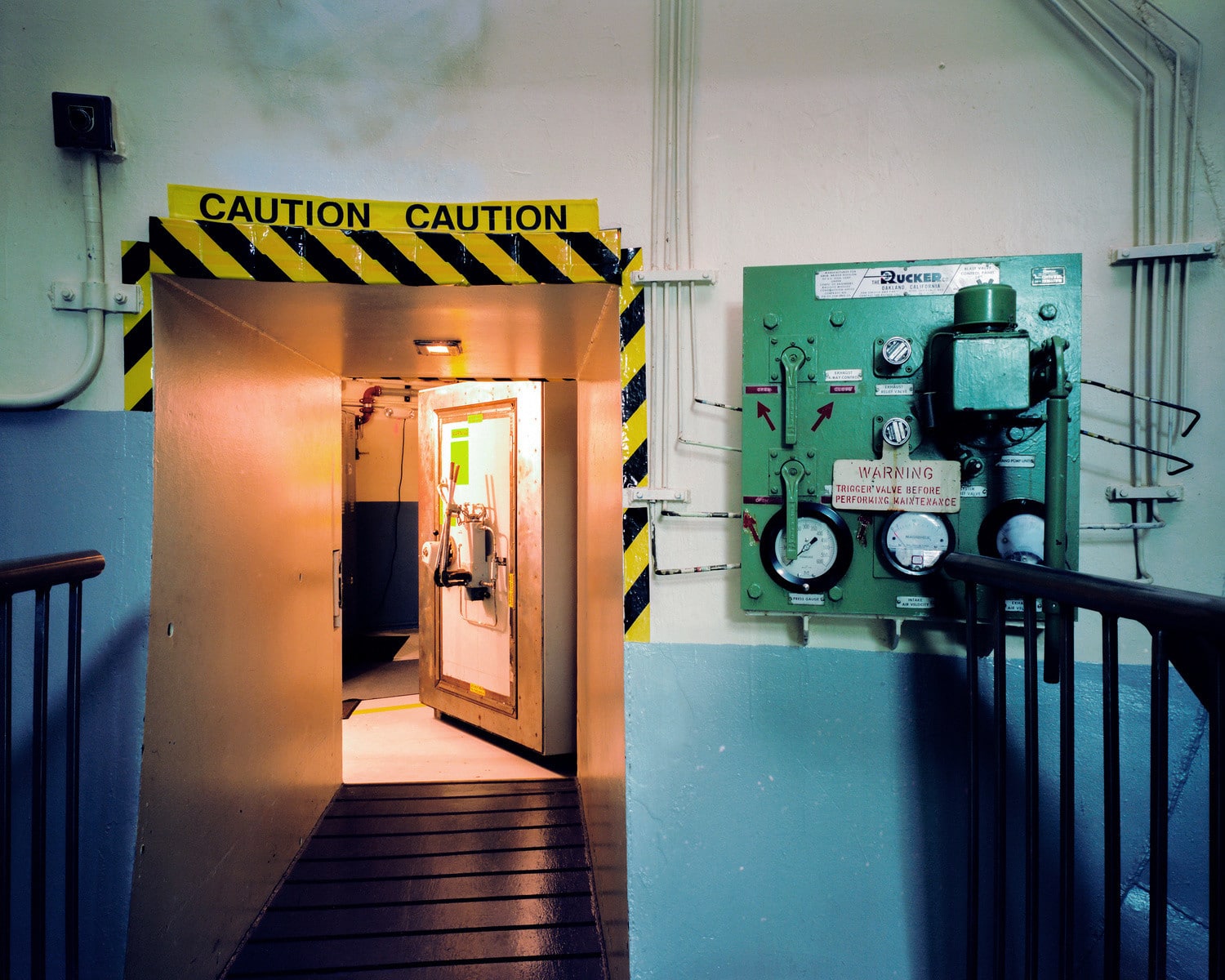

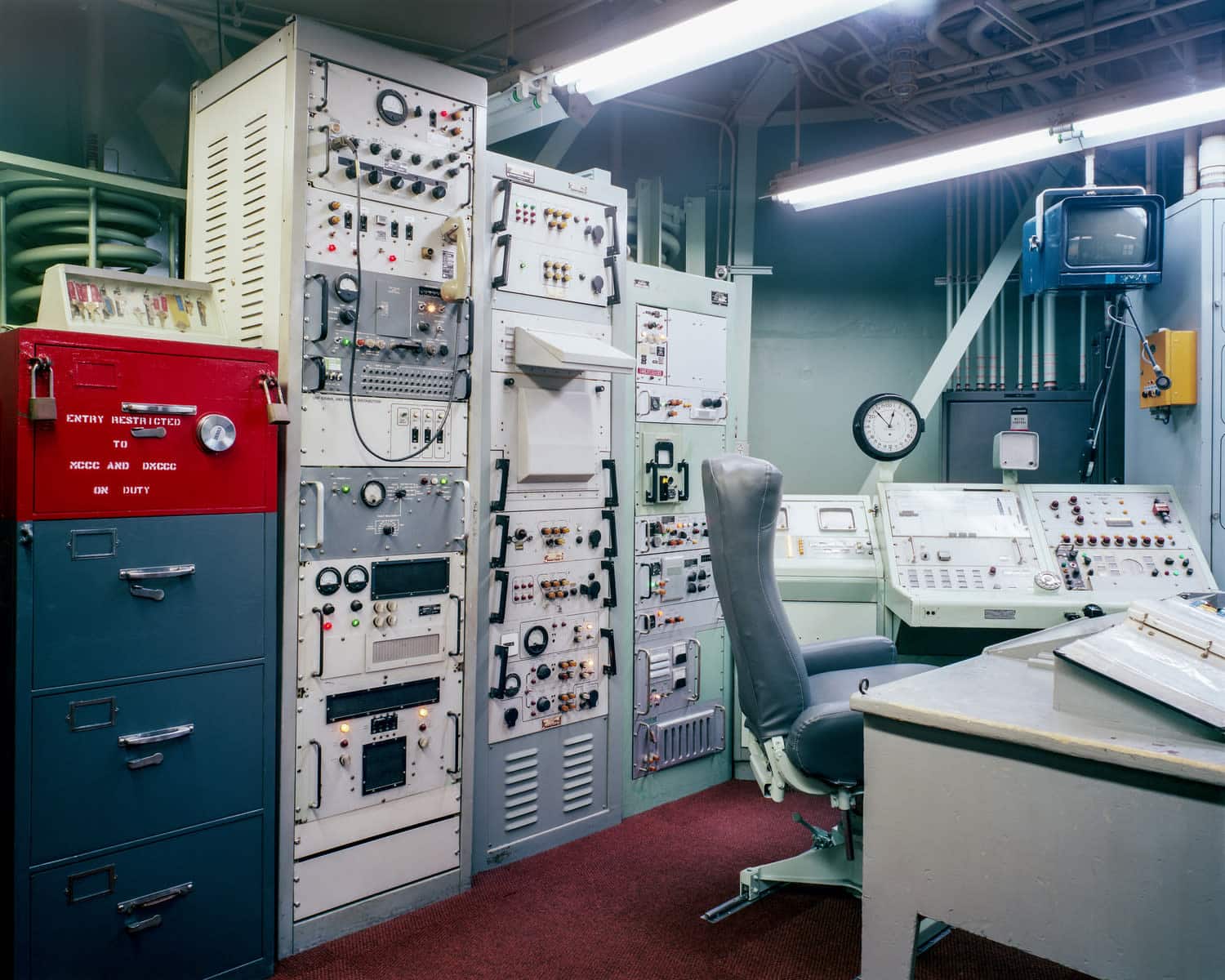

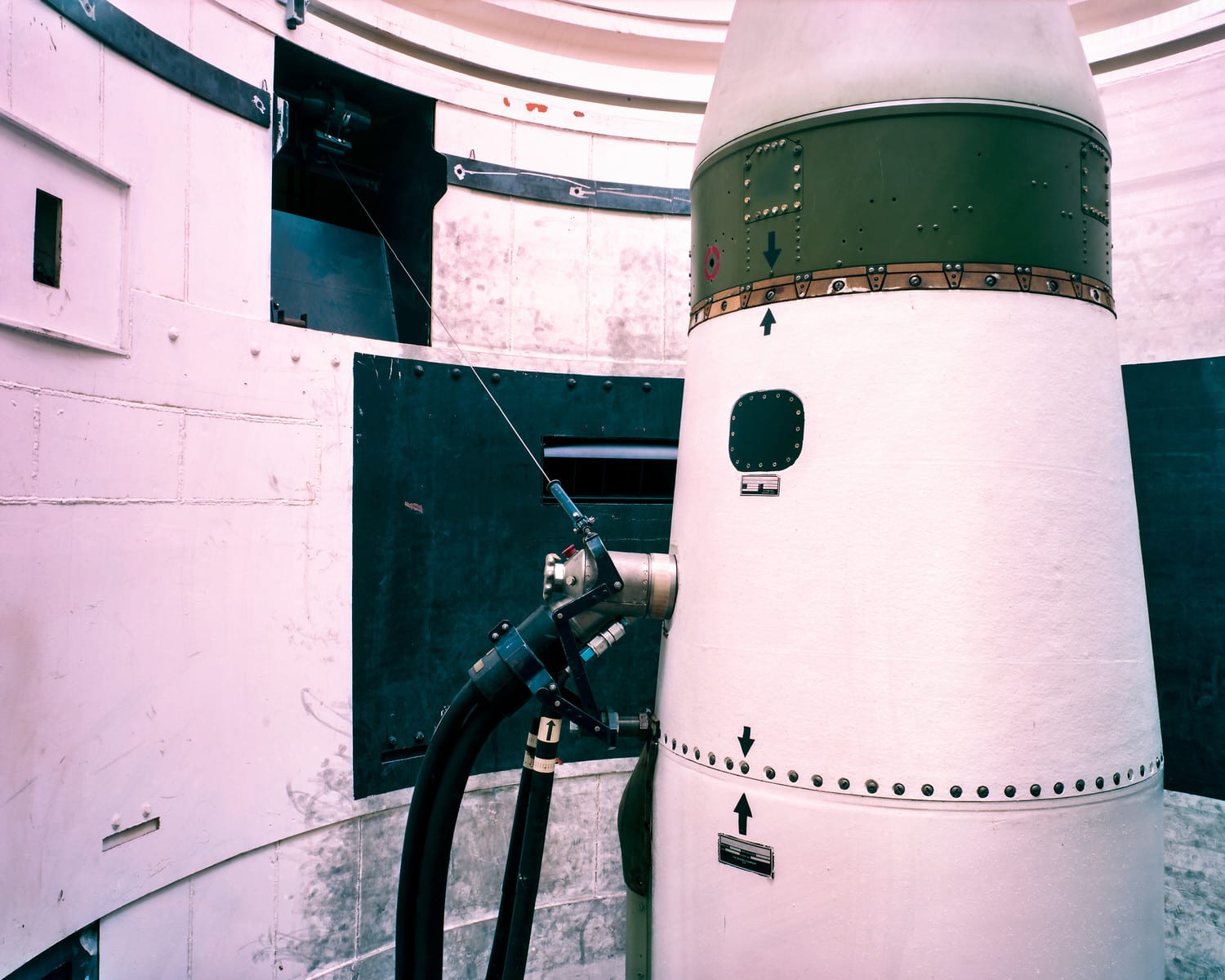

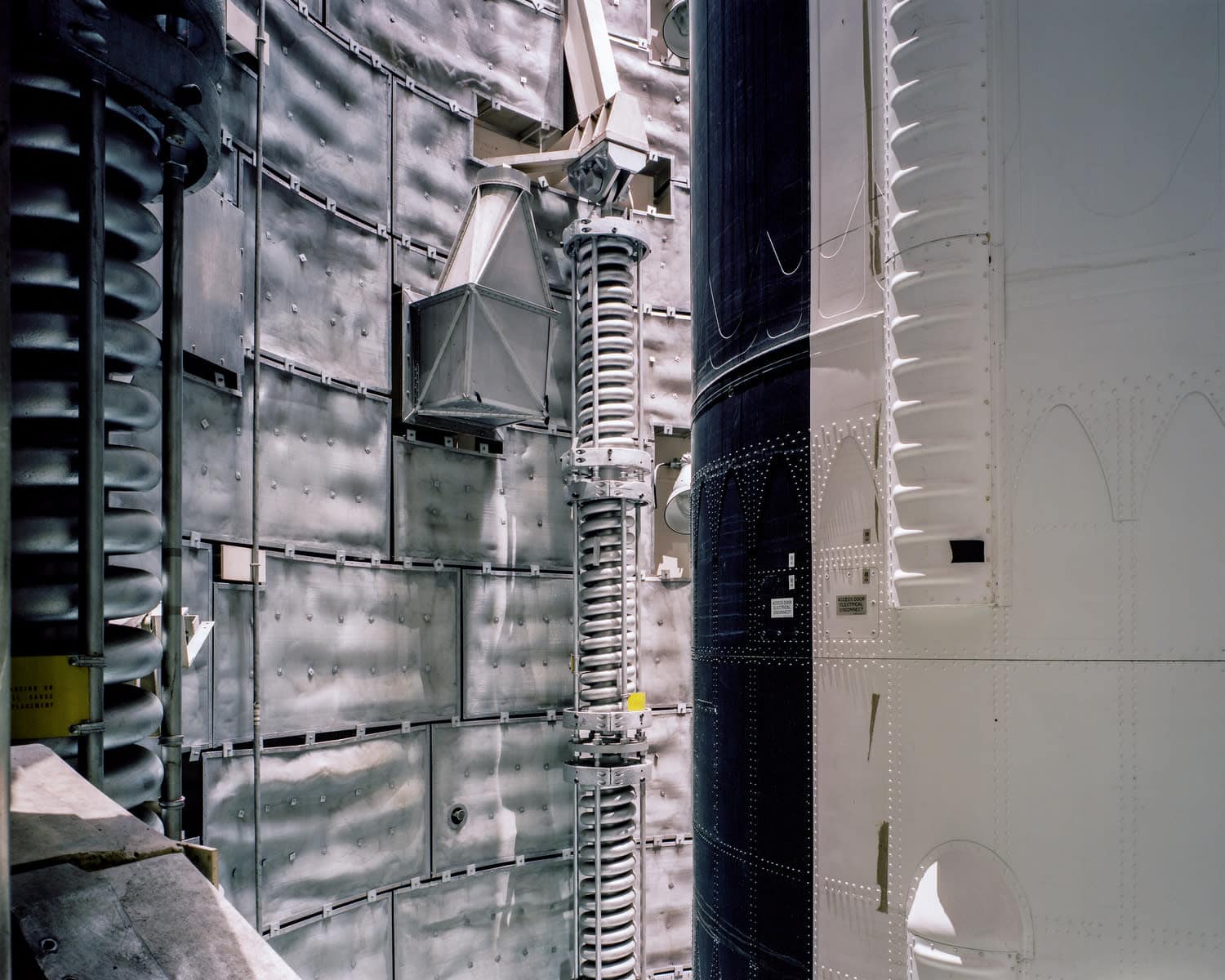

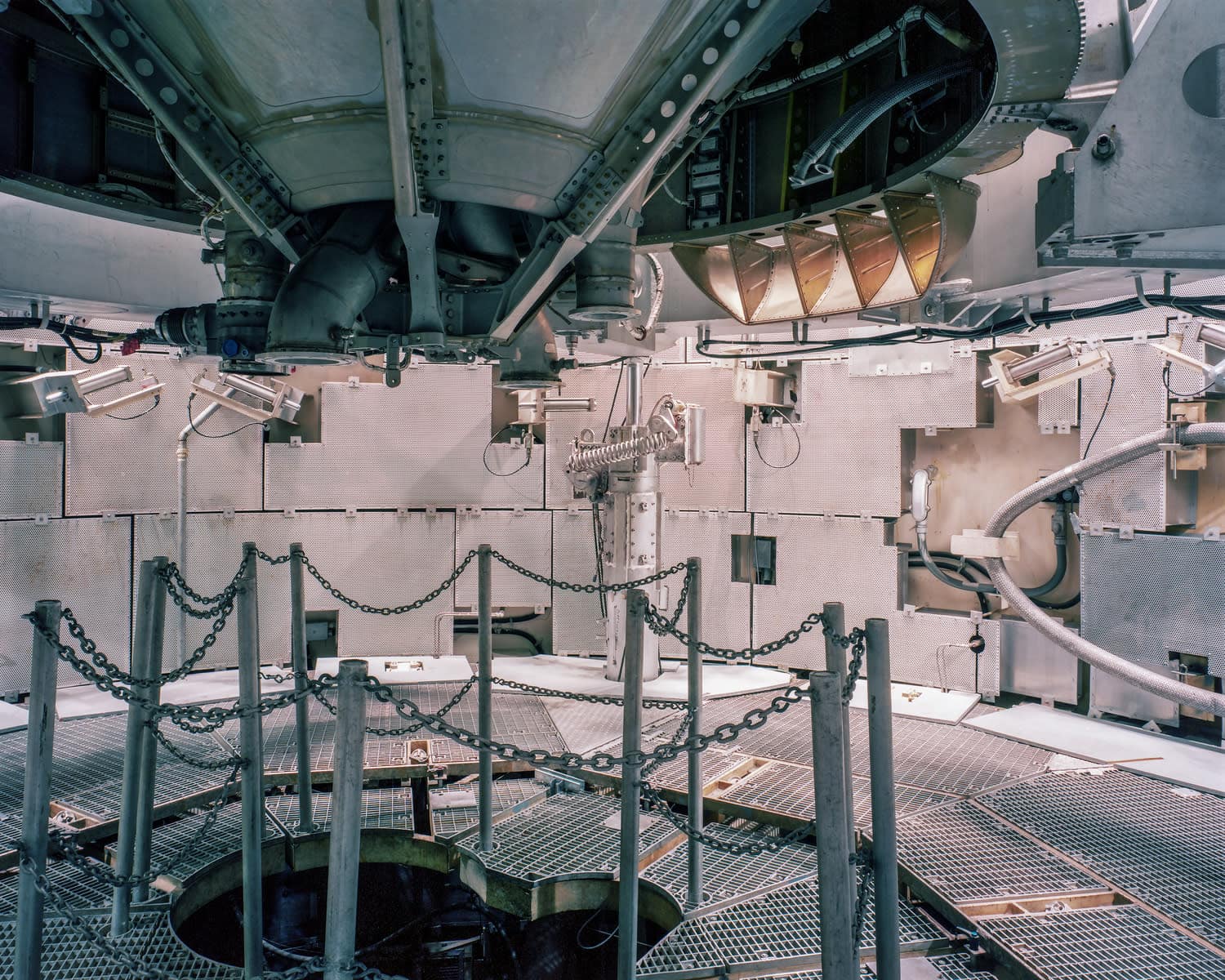

Estos dos emplazamientos turísticos, explica Reynolds en su declaración artística, "son los únicos emplazamientos de Misiles Balísticos Intercontinentales que quedan en Estados Unidos que no sólo permiten a los visitantes entrar en el centro de control de lanzamiento subterráneo, sino también encontrarse cara a cara con un misil balístico intercontinental (que no funciona)". Cuando la Guerra Fría estaba en su apogeo, escribe Reynolds, "Estados Unidos desplegó miles de misiles balísticos intercontinentales en una red de complejos subterráneos por todo el paisaje estadounidense. Estas armas nucleares constituían una parte de la vasta fuerza disuasoria de Estados Unidos cuando se enfrentó a su rival ideológico, la Unión Soviética, hasta su colapso en 1992."

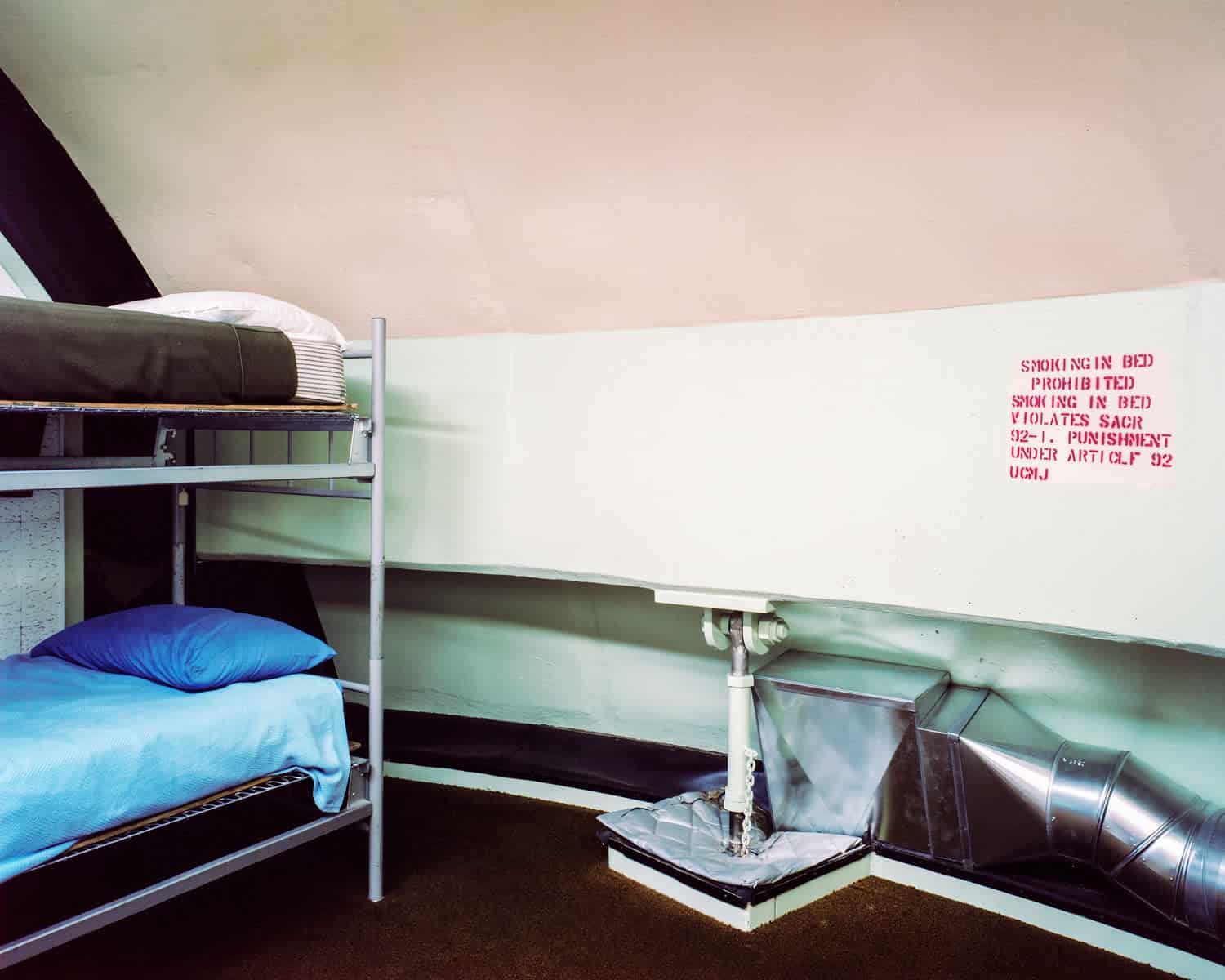

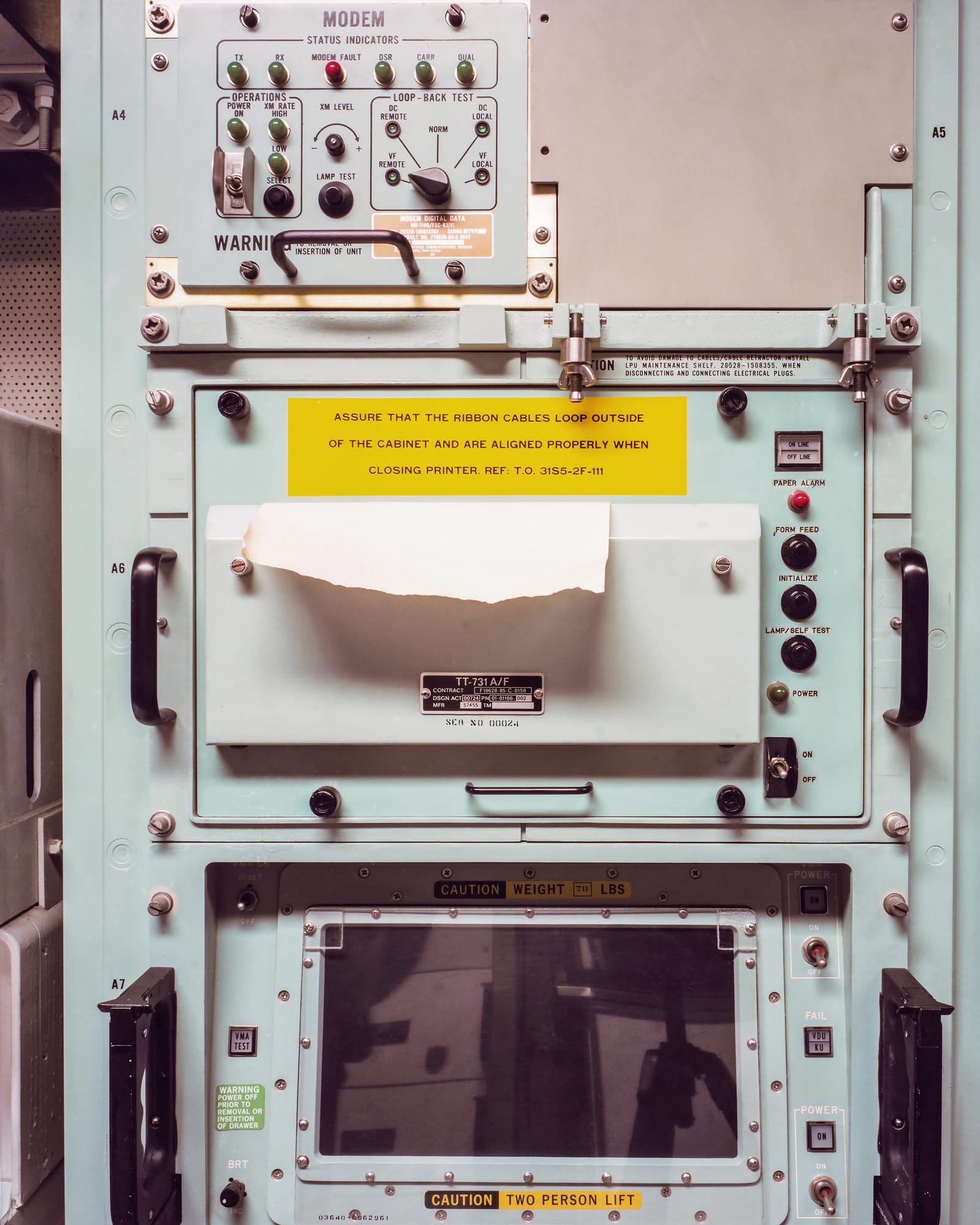

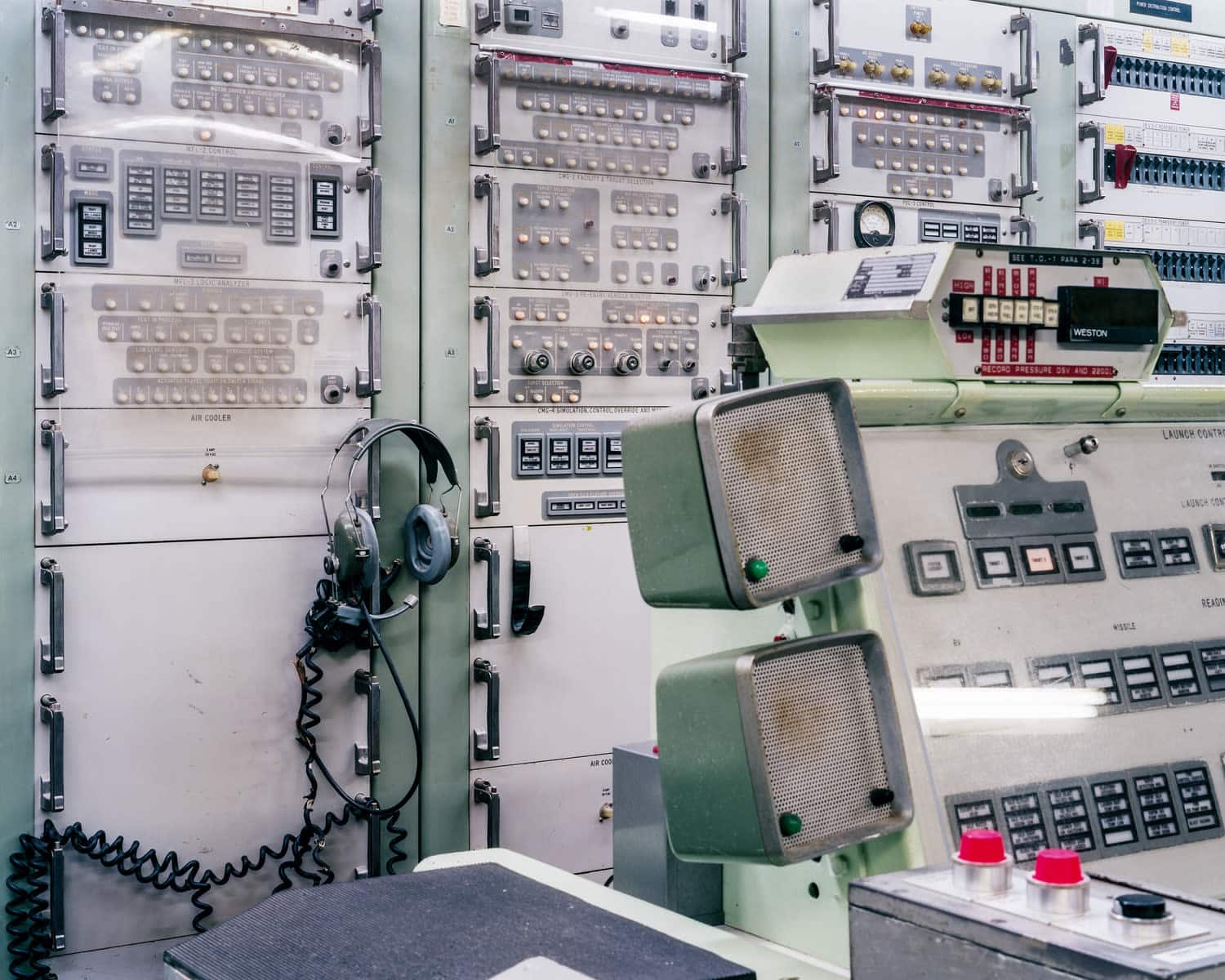

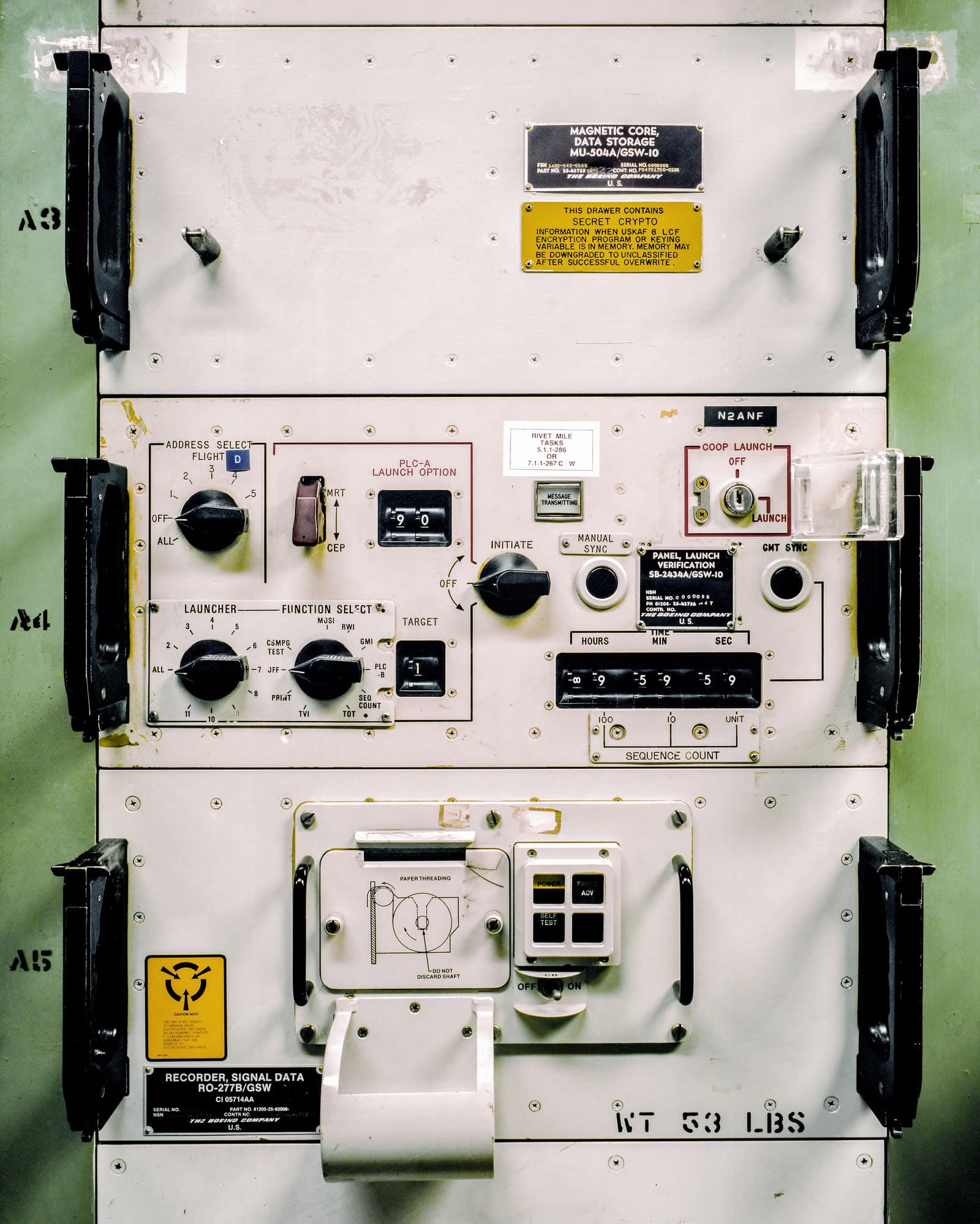

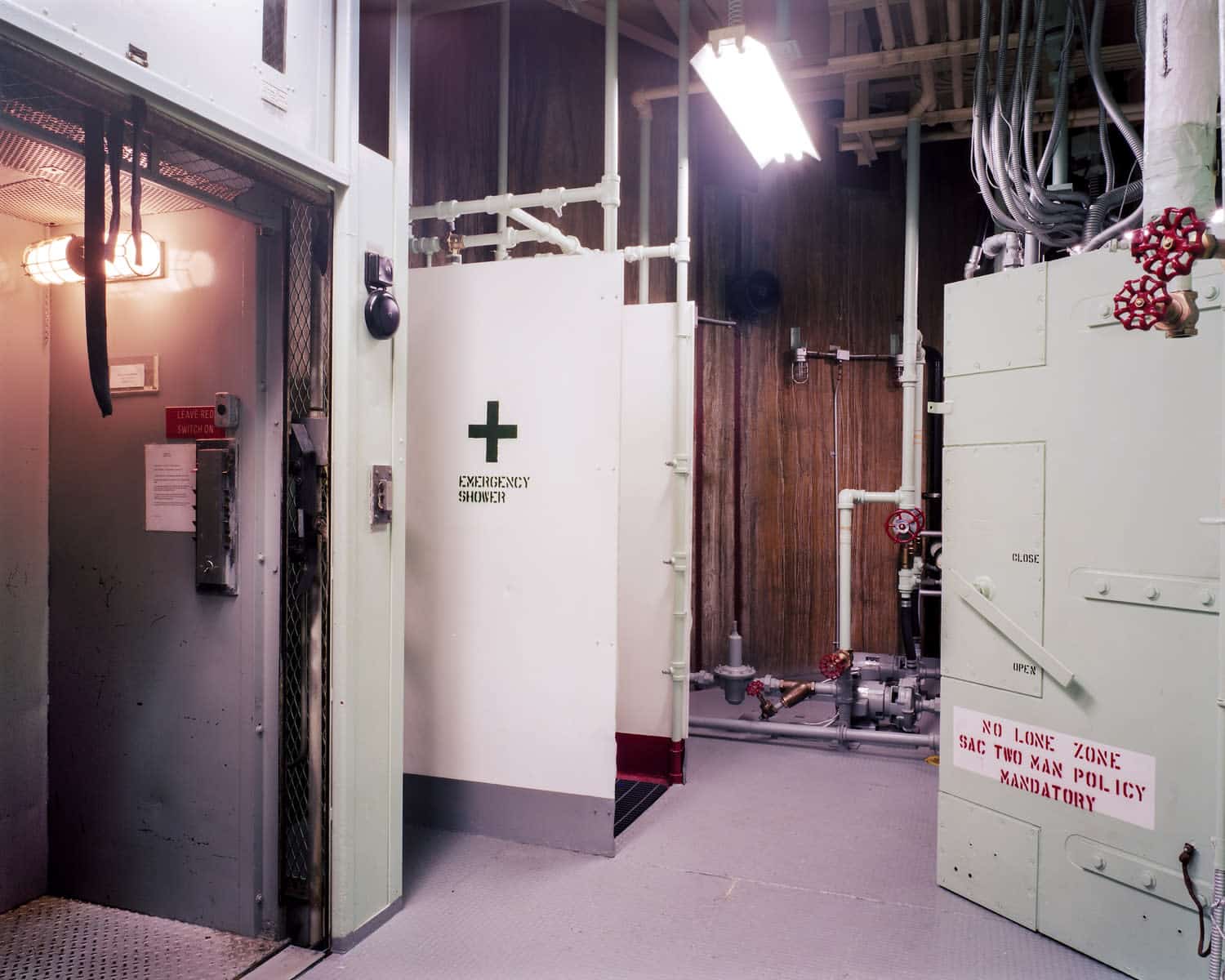

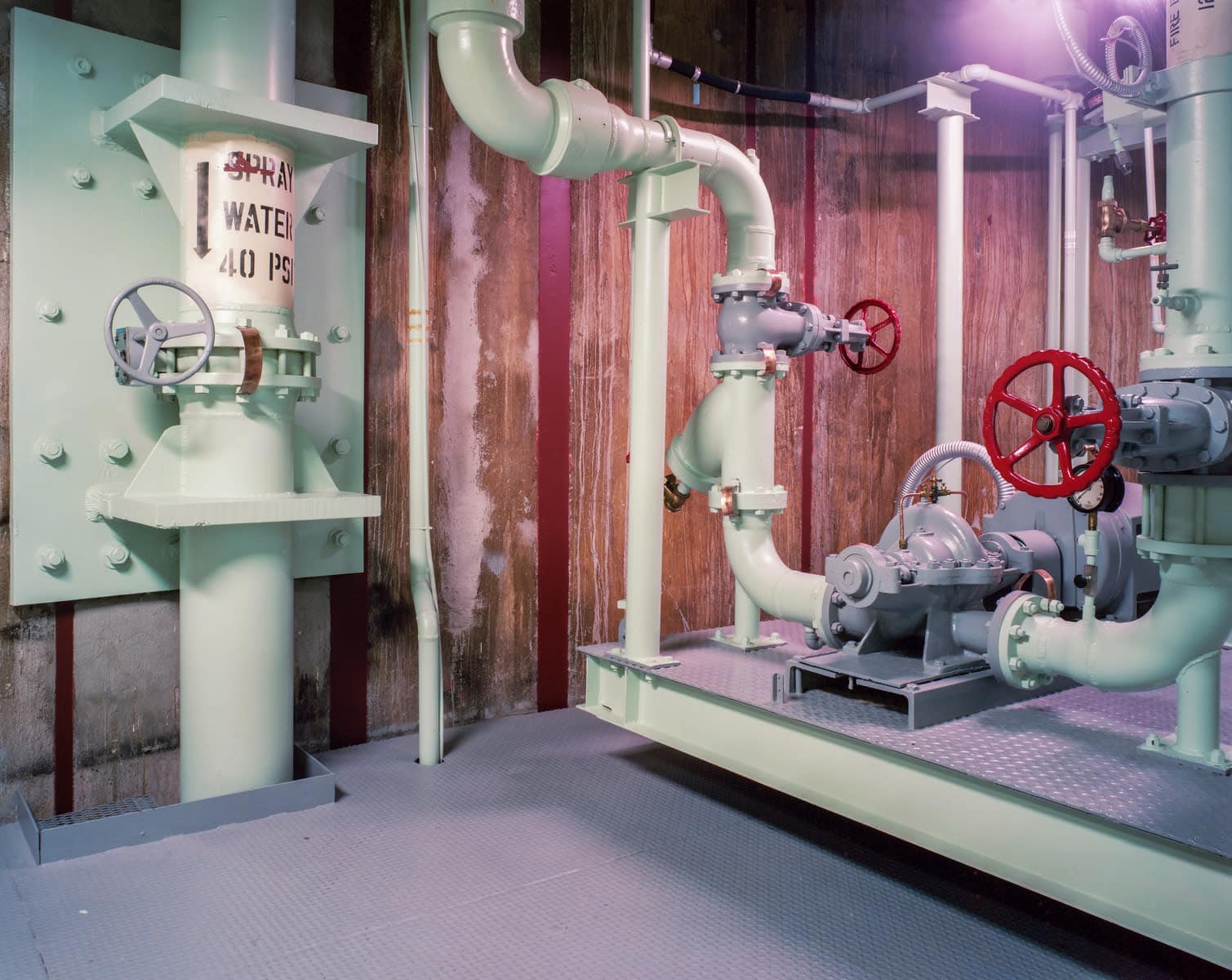

Las imágenes de Reynold de estos emplazamientos de misiles desaparecidos son inquietantes sobre todo por su banalidad, ya que muestran oficinas y literas, paneles de control y centros de lanzamiento, taquillas y salas de descanso. La serie fotográfica se titula No hay Zona Solitaria, una referencia al sistema obligatorio de compañeros de dos personas vigente en los emplazamientos de misiles balísticos intercontinentales. "Esto se aplicaba tanto a los oficiales de servicio en alerta las 24 horas del día en el centro de control de lanzamiento como a los equipos de trabajo encargados del mantenimiento de los misiles", escribe Reynolds. "La política pretendía ser una precaución de seguridad y una salvaguarda contra posibles sabotajes". Las imágenes de Reynolds, sin embargo, están llamativamente desprovistas de gente, ya que fotografió los museos en visitas guiadas privadas. Aparte de su vacío y de la evidente antigüedad de la tecnología de los misiles, la cuidadosa conservación de estos espacios históricos hace que parezcan prácticamente nuevos.

En efecto, la Museo del Misil Titán comercializa su gira como una especie de recreación histórica, anunciando en su sitio web la posibilidad de "viajar en el tiempo para estar en primera línea de la Guerra Fría". En Dakota del Sur, el Sitio Histórico Nacional del Misil Minuteman conserva de forma similar un antiguo campo de misiles que estuvo operativo "24 horas al día, siete días a la semana, durante 365 días al año, durante treinta años", como explica el sitio web del museo, y añade: "Mientras tanto, los terratenientes locales y los miembros de pequeñas ciudades del centro y norte de las Grandes Llanuras convivían literalmente con las armas nucleares." Estos dos lugares forman parte de una tendencia turística más amplia, sugiere Reynolds. "Con gran parte del arsenal nuclear estadounidense de la época de la Guerra Fría desactivado y desmantelado en la actualidad, hay un número creciente de antiguos emplazamientos de misiles cuya misión es preservar la historia y la memoria de la época".

¿Por qué un periodo tan tenso de la historia estadounidense inspira tanta reminiscencia? "Creo que la Guerra Fría despierta cierta nostalgia", dice Reynolds a Format Magazine por correo electrónico. "Puedes interpretar ese atractivo como una celebración de las proezas militares de Estados Unidos, o como un cuento con moraleja sobre el apocalipsis". Reynolds dice que la obra surgió de otro proyecto fotográfico, Arquitectura de una amenaza existencial, que examinó los refugios antiaéreos en Israel y los Territorios Ocupados. Sin Zona Solitaria es una continuación de la exploración de Reynolds de la infraestructura del conflicto político.

Puede resultar tentador pensar en los emplazamientos de misiles ICBM como reliquias de un pasado lejano, especialmente para los visitantes más jóvenes que no vivieron la Guerra Fría. "En cierto modo, las armas nucleares y la Guerra Fría eran sinónimos en la mente de la mayoría de la gente", afirma Reynolds. "Con el final de la Guerra Fría, la amenaza que suponían estas armas desapareció rápidamente de nuestra conciencia. Pero dada la trayectoria de la proliferación nuclear desde la Guerra Fría, esa amenaza sigue muy viva". Aunque muestra misiles envejecidos y sin funcionar, Sin Zona Solitaria funciona, sin embargo, como un incómodo recordatorio de que las armas nucleares no desaparecieron todas cuando terminó la Guerra Fría.

Ver más fotografías de Adam Reynolds en su sitio webconstruido utilizando Formato.

Más series fotográficas que exploran lugares insólitos:

Tangjialing, un pueblo chino destruido por la urbanización

Fotografiando rostros, religión y memoria en San Salvador de Jujuy

Los fantasmas de la fábrica de hilo abandonada de Croacia