Every year Frieze hosts an international art fair on Randall’s Island Park. With the focus on the top galleries and artists, there is still room to discover fresh talent in the Frame section of the fair, which is devoted to emerging artists.

The large array of ages, career levels, and backgrounds at Frieze makes for a fascinating experience. I was taken particularly by the multigenerational variety on view, which brought out the nuances in each work. When works overlap in time and style, different attributes are drawn out and accentuated.

The Frieze booths that stood out as most memorable are a combination of young artists and established names, a mix of sculpture, painting, photography, and more. As one of New York’s most major art events, there’s always a lot of talent on view at Frieze, but these are the booths that continued to prove thought-provoking even after the fair was finished.

Mira Schor, MA (me) MA , 1991. 48 x 100 inches. Oil on 12 canvases. Courtesy Lyles and King.

Mira Schor at Lyles and King

The works on view at Lyles and King’s Frieze booth looked contemporary, but were actually made in the 1990s and had not previously been exhibited. Why? I have no idea, because they are knock outs. Mira Schor’s works are bold but soft, politically engaging but poetic, and painterly-executed but with the sensitivity of drawings. Schor’s work made me think about the recent Judith Bernstein show that happened at Paul Kasmin Gallery. The room was full of images of penises, Day-Glo paint, and black lights illuminating depictions of Trump and Mau. I thought maybe I was a prude because I didn’t love those works. But Schor proved this wrong; I appreciate more complex portrayals. In Schor’s work, there is beauty and violence, and yes there are phalluses, but also much more.

In Schor’s Frieze works, we see uterus shapes superimposed on sperm forms, scrawled onomatopoeia cursive words, and the repeating motif of phallic heads locked into compositional diagrammatic geometries. I appreciate the contrast of controlled and graphic space against the looser, poetic interruptions of form and language.

Schor creates space for thought in her work, rather than combative argument. There’s definitely a position presented, but it’s evocative not dogmatic. The paintings produce an aesthetic and symbolic space to meditate in. I love the hurtful kind of beauty to these pastel, earthy, painted images. The variety of strategies and open interpretations here allow the work to open an honest dialogue around sex and gender.

Sonia Almeida. Courtesy the artist.

Jesse Wine and Sonia Almeida at Galería Simone Subal

This was a delicious booth. Both Jesse Wine y Sonia Almeida use a charming sort of shorthand in their creations, referencing the history of their media while also allowing space for humor.

Jesse Wine is a young British sculptor whose work explores bodily shapes in monochromatic or bright-colored, coated plasticine-esque forms which perhaps recall Henry Moore, or surrealist sculptors like Jean Arp who contorted and bent the body in clay and wood. These artists explored the violence of bodies in the context of new wars and existentialist thought. Wine seems to be reacting more to popular culture and to changing media, contorting the body in a cartoon way, and capturing a relationship to form that is indicative of our era.

Portugal-born, Boston-based artist Sonia Almeida makes paintings in a similar fashion. Her works are candy-colored, referencing simplistic cartoon backgrounds and stripped-back abstract formalism. Thinly painted, both in amount of layers of paint and in the body of the paint itself (it’s watered down, and loose in parts), Almeida’s work also reveals sophisticated and well-planned compositional trickery. In one painting, the layers of washes devise a complex geometry of shadows. In another case, her painting is literally able to roll two wood panels apart, revealing a thinly painted rope unravelling as one canvas slowly becomes two. The painting is visually roped together, in an elegant yet tongue-and-cheek execution.

Merrill Wagner, Untitled A and B, 1978. Courtesy the artist and Zürcher Gallery, New York.

Merrill Wagner at Zürcher Gallery

Zürcher Gallery’s booth at Frieze was almost a representation of their exhibition with Merrill Wagner’s work last year. Wagner, born in 1935, is finally receiving recognition as a post-minimalist materialist painter.

Most of her work on display at Frieze featured a unique process, using fabric tape and plexiglass, that Wagner developed in the 1970s. What makes her monochromatic minimalist paintings unusual is her interest in the degradation and lifespan of pigments. Inspired by the long history of pigments as alchemy, Wagner draws on the representations of paint as an earthy material, manipulated and splayed upon surfaces in the service of human expression. Some newly displayed Alizarin Crimson-colored tape paintings stood out in particular for their rich hues. The variety of saturation and slickness upon the surface brought the work to life. Like a Rothko, it shimmered as you walked back and forth before it, with the unassuming monochrome glowing and receding.

It was also a pleasure to see some of Wagner’s landscape intervention photo documents displayed in a grid. Wagner, who spends time in the countryside, created a body of work in which she did paintings outside, on fences in the surrounding landscape. During their lifespan she photographed their decomposition in situ, watching sunlight and weather make changes upon the work. Wagner speeds up the entropic nature of painting and speaks to it within the landscape at the same time. There’s a beautiful book work on these pieces that shows a fuller ranger of these performative paintings.

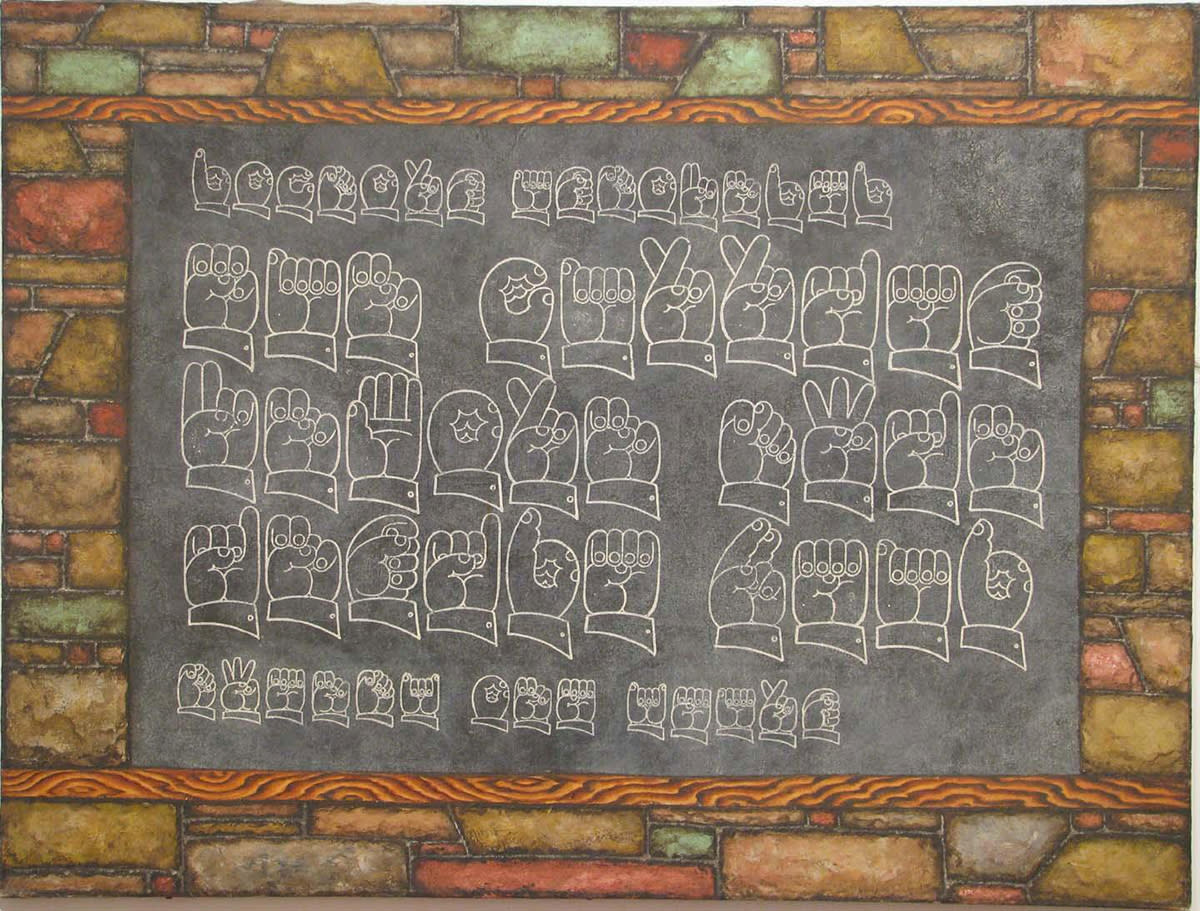

Martin Wong, Man Carries Unborn Twin Inside His Head 21 Years, 1982. 36 x 48 inches. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy P.P.O.W. Gallery.

Martin Wong and Peter Hujar at the back room at P.P.O.W. Gallery

Both these artists were on view in the back room of P.P.O.W., a gallery with great programming. I did like the work prominently featured in the main space, but I really loved seeing some gems in the closet space by artists I admire and didn’t expect to see. This is the thing about art fairs; there is always the main event—the planned booth—but the beauty of fairs can be their hidden surprises. The conversations between people meandering through the halls. The art handlers the day before unwrapping the pieces like presents. The backroom can be a magical space. It can contain works that were just discovered at an artist studio or estate.

At the P.P.O.W. booth, I found two works representative of the estates of Martin Wong y Peter Hujar, who both worked predominantly in the 1980s and made work that dealt with the AIDS epidemic, figurative relationships, and identity. Hujar is best known for his introspective black and white portraits, while Wong, a Chinese-American painter, paints with highly highly personal and repetitive motifs. His works are some of my favorite that I’ve had the pleasure to learn about since moving to New York, and I loved having the opportunity to explore his work once again.

Hans Breder, Ikarus, 1974. Photographic still from Ikarus. Courtesy Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Hans Breder at Ethan Cohen Gallery

While I thought Ethan Cohen’s booth furniture was a huge distraction, I found myself able to push it out of my mind’s eye. This allowed me to focus on the elegant performative work of German-born artist Hans Breder, revealing a provocative room of simple objects and body propositions in filmic and photographic space. Breder, who passed last year at the age of 81, deserves this attention on his work. Often using the body as subject, Breder’s practice balances itself between notions of sublimity and domestic simplicity. These two sides of the artist’s scale are interesting to see balanced in his stripped-down, low-fi strategies of image- and film-making.

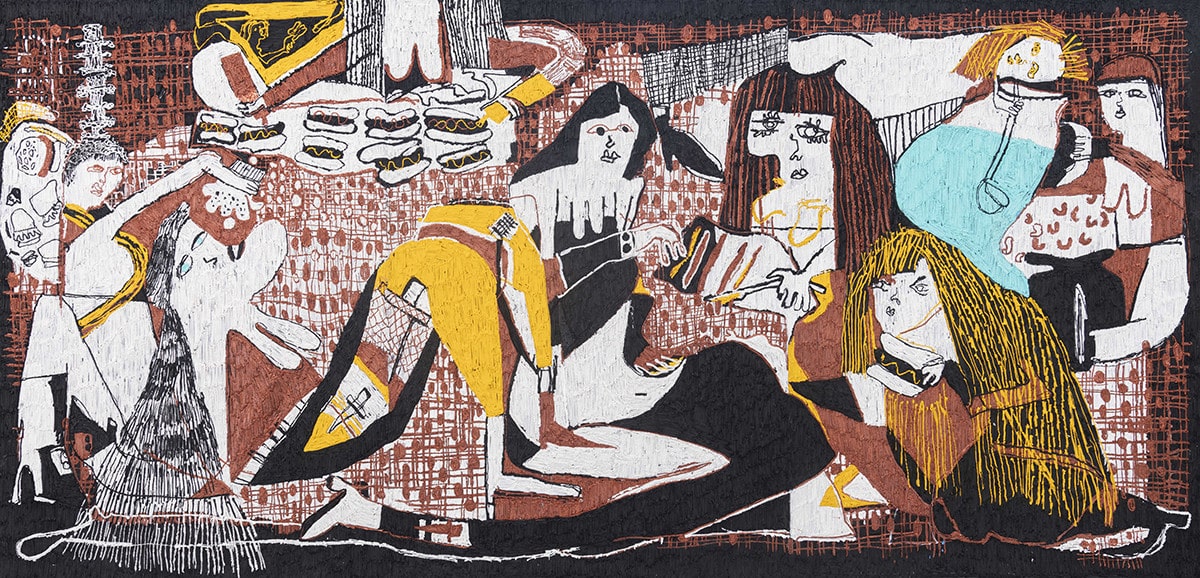

Summer Wheatley, Picnic with Ketchup and Mustard, 2018. 74 x 144 inches. Acrylic on aluminum mesh. Courtesy Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Summer Wheat at Andrew Edlin Gallery

I’ve been a fan of Summer Wheat’s caustic, obsessive paintings I first saw her work at the Triangle Artist Residency in 2010. Frieze was the first time I’ve viewed these new paintings on aluminum screen. From a distance, they appear as lush, sculptural shiny paint rugs. Wheat has developed this new technique: she works the acrylic paint on the backside of the screen and then pushes it to the front, simulating thread like forms of paint. Previously an oil painter, it makes sense that Wheat is now using fast-drying acrylic instead for this new application. The process must be both laborious and freeing. It’s exact and imprecise at once.

These works are full of the symbolism and story-telling typical in the history of narrative tapestry. The subject matter harkens back to some images I saw in 2015 on a studio visit. Here we see picnics, bodies, objects, ceramics, patterns, night skies, and the landscape. The works remind me of scrolls or meandering panoramas. Their sprawling length, immersive quality, and minimal palette implores you to spend time deciphering their technique, hidden images, and exaggerated sense of space. I’ve long admired Wheat’s work, and these new paintings seem to synthesize her interests between craft, paint, subject, and technique.