Most democratic countries allow convicted criminals to vote, with many making it possible for prisoners to vote even while they are in jail. But across the United States, more than six million citizens are denied the right to vote because of prior felony convictions. 48 states prohibit incarcerated people from voting, and four states actually block those who’ve served time from ever voting again—unless they petition a court to get their rights back.

On November 6th, citizens of one such state have the chance to approve a ballot referendum that would restore voting rights to 1.4 million disenfranchised people. This state is Florida, which, along with Kentucky, Virginia, and Iowa, and has some of the strictest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. Currently 1.6 million Florida citizens are blocked from the ballot.

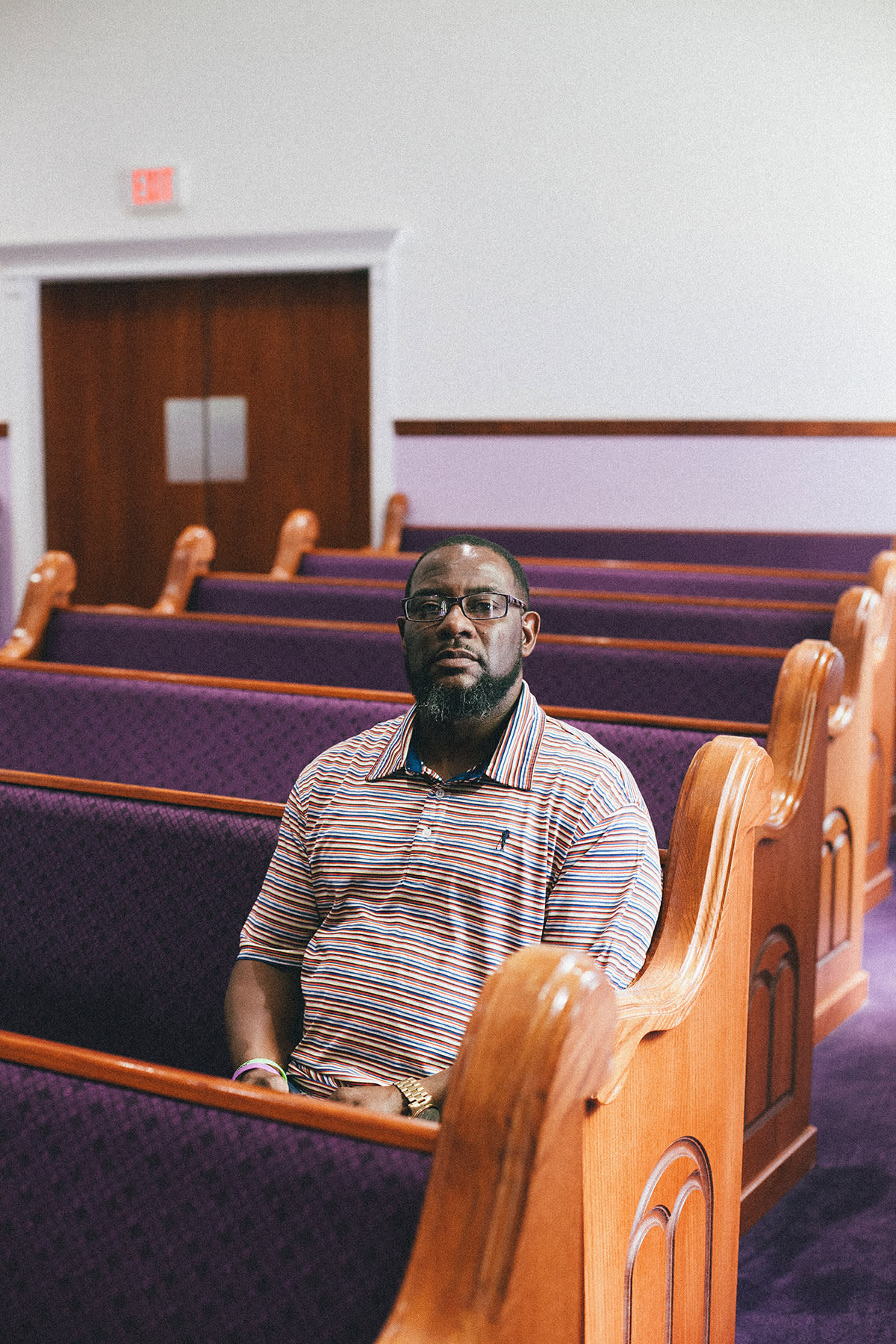

Kelsey Aroian isn’t a Floridian, but the creative director decided she wanted to help get the word out about Amendment IV. If it passes next month, says Aroian, this amendment will result in the greatest act of enfranchisement in decades. Blocked from the Ballot is Aroian’s effort to educate more people about this historic opportunity, through a photo and interview series that shares the stories of individuals fighting for voting rights in Florida.

Aroian believes that a lot of folks, especially in “in very progressive parts of the United States, don’t know that voter suppression is alive and well and having a massive resurgence.” Blocked from the Ballot aims to give a face to the people who are personally impacted by disenfranchisement. Aroian teamed up with photographer Aundre Larrow, designer Jessica Strelioff, and editor Nicholas Firchau to create the web-based project. “Having access to the ballot is a basic right of all citizens in a democratic country and in a democratic society,” says Aroian. “This isn’t an issue about politics or party. It’s about people. Everyone in our country should have a voice.”

Blocked from the Ballot features a diverse selection of people from a range of political and cultural backgrounds. Aroian made it a point to keep the project non-partisan. “You have people of all different socioeconomic backgrounds, different races, different walks of life. Every single person there is coming together for Amendment IV,” she says. “I’m disgusted by partisan politics in our country right now, and yet I would never in a million years wish upon anyone that had different views than I did that they couldn’t go to the ballot and express their voice.” However, adds Aroian, “unfortunately it is a pretty partisan issue, because a lot of Republicans are blocking access to the ballot with voter suppression efforts.”

Blocked from the Ballot demonstrates how difficult it can be for people in Florida to get their rights back after serving a criminal sentence. Even for those who’ve worked hard post-prison to rebuild their life and give back to their community, clemency can still be denied. For Joey Galasso, a small business owner who says he came out of prison a changed person, the news that his clemency was denied because of a few speeding tickets was a devastating blow. “[Florida governor] Rick Scott said there’s no laws or no standards or anything for this process, and he can do what he wants when it comes down to giving people their rights back,” Galasso says.

In Florida, a full 10% of the adult population cannot vote due to prior felony convictions. People of color are disproportionately affected, with one in five African American adults in Florida unable to cast a ballot. According to Aroian, this is emblematic of the nationwide issue of disenfranchisement. “It’s very much about race across our country. By suppressing the vote you’re disproportionally affecting people of color, and that is the case in Florida.”

Florida is photographer Aundre Larrow home state, so this project held some special importance for him. “It’s about building empathy,” he says. He also notes that the question of whether or not convicted felons should be able to vote can bring the efficacy of the criminal justice system into question.“If we think that people are being rehabilitated, then they should be able to vote. If we don’t think they’re being rehabilitated, then we have to ask a question about the criminal justice system.”

Aroian hopes that Blocked from the Ballot can inform people about the important impact Amendment IV can have—and perhaps change some minds as well. “It’s easy to make a blanket statement: ‘I don’t think that felons should have the right to vote. They’re not good decision makers.’ But I think it’s a lot harder to make that argument once you’ve heard someone’s personal story.”

See the full project at www.blockedfromtheballot.com.

Pastor Deanna Smith, Faith Lead for the Florida Rights Restoration Council: “I’m always trying to bring churches together, to get them to understand it’s not always easy making change. Years ago we was taught state and church didn’t have no dealing. So I’ll go to some of the pastors and they’ll say, ‘I’m not dealing with politics.’ So I’ll say, ‘What about a second chance? What about forgiveness? Do you deal with that?’”

Susanne Manning, Reentry Coordinator for the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition: “There’s a guy and his wife in my neighborhood who are very old-fashioned kind of people, and I knocked on their door a while ago to talk about Amendment 4. And the guy asked me, ‘Why the hell do you care about convicted felons?’ And I told him I am one. And he said, ‘But your yard is immaculate!’”

Neil Volz, Political Director for the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition: “I’ve been personally involved since 2015. I’ve crossed the entire state of Florida in my car. I’ve got more coffee cups and T-shirts in there than you could imagine. I’ve had so many conversations at churches and coffee shops and community centers and people’s houses, and it’s been amazing to see people put something like this on the ballot.”

Yraida Guanipa, founder of the YG Institute, which works with families affected by prison: “When you finish you sentencing, you’ve paid your debt to society. But that record goes with you for the rest of your life. It doesn’t only affect me, but affects my children and my grandchildren because there will always be someone over there that will be bullying my grandchildren saying, ‘Your grandma was in prison for 11 years.’”

Lovell Lee, military veteran and community organizer: “It’s a lie that your vote don’t count, because every single vote in Florida does count. It gets frustrating sometimes because everybody’s not gonna get it, but I’m gonna keep it moving and I’m gonna keep depositing as much as I can in as many people’s lives as I can.”

Joey Galasso, small business owner and youth mentor: “I’m always gonna be the man that I am, and whether I get a voice or not is not gonna change it. But I want it to be easier for those coming out. I don’t ever want them to feel like I did, because some people might not be able to handle it.”

Geraldine Harris-Harreo, caterer and community organizer: “That vote you think that doesn’t count is the vote that puts a light on your street. That vote helps bring in jobs needed in your city. You’ve got a voter registration card, and you’re not taking the opportunity to go and make a difference in your own county?”

More on current events and photography:

Nation of Newcomers documenta las historias cotidianas de los inmigrantes en Estados Unidos

Andrea Sceresini Makes Films in the World’s Most Dangerous Conflict Zones

La fotoperiodista Emily Garthwaite ve la fotografía como una terapia