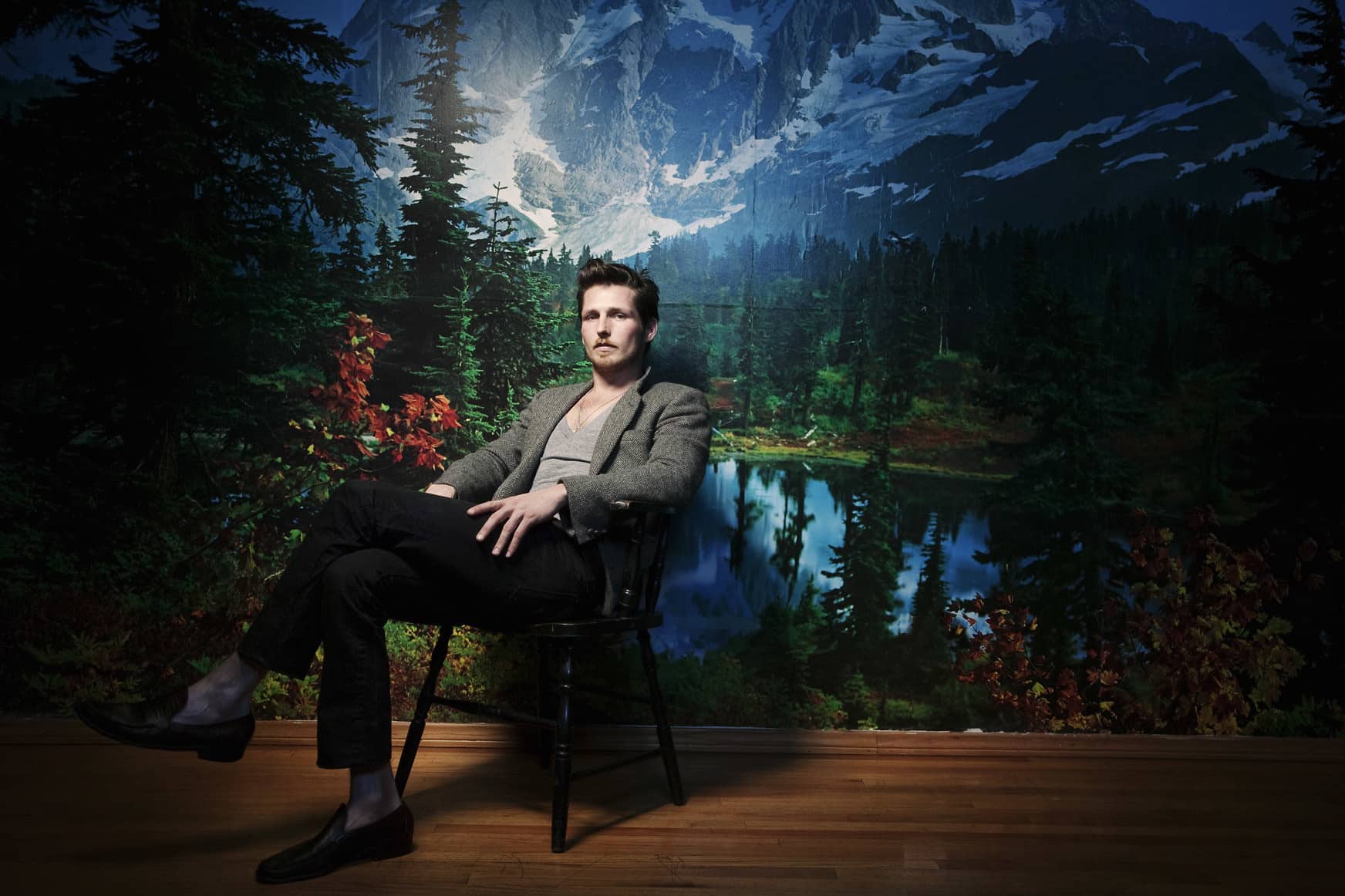

Chad VanGaalen landed on the music scene’s radar with the eerily gorgeous Infiniheart in 2005, and has since become a bit of an explosive creative force, working at a level of productivity that boggles the mind. He’s designed puppets for Adult Swim, produced numerous critically-acclaimed records, and won the 2015 Prism Prize for his Timber Timbre’s “Beat the Drum Slowly” animated video. But it’s time to slow down. As a noted world-builder, he’s used to living in the worlds he creates, and his latest album, Light Information, is one he’d rather steer clear of right now.

“The world of Light Information is pretty stressed out,” VanGaalen says over the phone from his home in Calgary. “The world of Light Information is not the world I wanna be in anymore. I just feel like it was a lot of struggle. It was me getting over the fact that, as time and your mind slowly unravel, things become less clear. I’m sick of feeling like that’s a ripoff—I just don’t wanna turn into a grumpy old man.”

Like most self-employed creatives, there’s a lot at work in VanGaalen’s mind that could be causing the stress, and he’s working on leaving behind. “I have to keep my boat afloat,” he says, talking about the push to produce. It’s an impulse fuelled by the need to support his family. But lately he’s been focusing his energy on learning to balance himself out, staying healthy, spending time with his daughters, gardening. It’s a goal worth working toward, and one that’s tough to maintain when you’re your own boss and janitor, and you need to keep the lights on. Is anything ever really worth the burnout? Light Information addresses and deals with a lot—it’s complex and strange and beautiful, and exists in a world where parenthood, age, and changes in perspective are altering VanGaalen’s outlook.

My ass feels like it’s not even there anymore half the time. So I’m throwing myself in the river and literally bumping my ass down the river on the fuckin’ rocks to wake my ass up. It’s fuckin’ crazy. Ass therapy.

“It’s kinda growing pains, really—me coming to terms with the fact that in order to make these animations, it takes a lot of screen time,” VanGaalen says. “I’m forced to sit and be in front of a computer eight hours a day for two months at a time. It’s just not a healthy way to be. My body, you know, like, my ass feels like it’s not even there anymore half the time. So I’m throwing myself in the river and literally bumping my ass down the river on the fuckin’ rocks to wake my ass up. It’s fuckin’ crazy. Ass therapy. It’s no fun to sit. I built myself a standing workstation a couple years ago, but whether you’re standing still or sitting still, sedentary is never good for the human body. There’s a reason animators are super weird and die when they’re 42 years old.”

“I totally love making art. It’s just that maybe I could do it while I was like, swimming,” he laughs.

Of course, it was his partly obsessive tendencies that eventually catapulted VanGaalen into this creative lifestyle. It’s a job where he’s able to create his own universes and characters and inhabit their worlds, and make a living off of it. He can remember the early drawings he’d get in the mail, sent from his dad, a landscape painter, and how they inspired him to set down this path.

VanGaalen mentions that he was at his father’s assisted suicide only a couple weeks ago. “Broken Bell,” from his new record, addresses their relationship and his own anxiety about mortality as he sings, “I sit and do a drawing, a portrait of my dad/I should really visit him before he’s dead.” Death and its strangeness is manifest in a lot of his work, but he rejects the idea that the fascination is morbid.

“It’s not like you’re taught to prepare for your parents dying or your kids dying or anybody dying, for that matter,” VanGaalen says. “I feel like Westerners are kind of in the dark as far as death goes. So I don’t feel bad about that, I don’t feel like death is necessarily a topic that’s stranger than anything else, really.”

As a young father, he’s also now acutely aware of the fact that his kids will get older and one day probably look up everything he’s done online. He says there’s an obvious responsibility involved with that sort of thing in being a parent, but he’s not about to shield his kids from what he’s created, either.

“My art has always been pretty honestly weird, in the sense that if I feel weird about it, I’ll probably turn it into a drawing,” he says. “I feel like that’s okay. That’s okay to expose children to that type of weirdness. It’s not like a vengeful weird. It’s not a hate-filled thing. It’s more of a cosmic weird feeling. So I don’t really feel too bad about it.”

My art has always been pretty honestly weird, in the sense that if I feel weird about it, I’ll probably turn it into a drawing.

His mother, he says, “was stoked” to have a kid with such an obvious artistic inclination and passion, and whenever he’d finish off a box of pencil crayons, he’d turn around and there’d be a new set along with a fresh sketchbook. He made the decision early on that he wanted to be an artist when he grew up, and from there, progressed toward drawing superheroes, eventually discovering things like Robert Crumb, Heavy Metal Magazine, Moebius, Watchmen, and of course, portadas de discos. But he credits the beginning of his animation work as the first step toward developing his signature style—a fluid and blossoming psychedelia that feels sometimes unnervingly real.

“I got into a real heavy line when I started animating because of the colour fill technology that was happening in Toon Boom at the time,” VanGaalen says. “I felt I had to close my lines up in order to colour fill everything. It’s strange how the type of medium will govern your aesthetic, and animation ended up lending itself to pretty cartoony, black line sorta stuff. That also comes out of Los Simpson y Beavis & Butthead and stuff like that, that I was obviously exposed to growing up.”

His approach is usually as fluid as the art that it produces. VanGaalen considers most of his characters to be of one universe. For example, the guys in the “Pine and Clover” video he just did are in the “same galaxy” as the ones in his video for “Peace on the Rise.” And he prefers to let those characters flow from his mind as they pop into it instead of over-structuring his work.

“With animation, I feel like in order for me not to get bored, I’ll allow myself to go on more of a tangent and not really storyboard something,” VanGaalen says. “It’s just so labour intensive, and if I know what the ending is going to be, it’s really hard for me to stick to that for two months straight. It can get pretty sloggy if you don’t allow for some improvisational morphing. Like, ‘Oh, you know what? Fuck it, I’m just gonna make this guy’s head a carrot. I don’t give a fuck what everybody thinks!’ I have to do it. I have to do it for myself.”

As a kid, VanGaalen promised himself that he’d find a way to make art full-time and really worked on making that a reality. His studio, which he built himself and has been working on in “different manifestations since I was about 15,” reflects the atmospheres he needs when he needs them. Right now, it’s filled with wool blankets, he says, and he’s been collecting driftwood and plants to replace other things. He’s gotten giant, pristine windows that were just discarded in the trash.

This transformation of space reflects the transformations he made in his visual art, working toward animation. Using 16mm film back in the day made things difficult because he was at the mercy of something he couldn’t see until it was developed. But then digital photography took off in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I can make this happen in front of my face now,’” he says. He was consumed by it, and says he overdosed a little on it, but has managed to find that balance between both worlds now. And that wisdom has come along with the same knowledge that makes Light Information feel so anxious.

“People just get so fuckin’ busy. And at the end of the day, it’s like, ‘Okay, sweet. I was making Punky Brewster burst out of a raptor egg and then explode into a bunch of Furbys.’ Really? Is that worth doing instead of going for a bicycle ride with my daughters? Probably fucking not. At the end of the day, I just feel like the consequence of trying to always be manifesting some sort of product is that you’re sacrificing these real moments with real people.”

The consequence of trying to always be manifesting some sort of product is that you’re sacrificing these real moments with real people.”

But it’s easy to tell there’s a hint of skepticism in what he’s saying, like it’s hard to truly combat a workaholic nature. He mentions that he’s not 100% sure about his new mandate, that maybe this effort to ramp down could be a mistake, that maybe he should be ramping up.

He says that he imagines hilariously tragic scenarios like the rise of virtual reality and being forced to master that, spending all his time with a digital family instead of the one in his home and eventually not being able to tell the difference, losing his grip on reality. He’s sincere in his desire to fight that sort of outcome, and he spends a lot of our conversation getting to the heart of one of the bigger issues of the modern era, a question that a woefully small, but one that a rising population of professional creatives ask themselves: What’s the point of this?

Content farms have exploded into such high rates of production that they’ve built unreasonable demands of their producers, and that attitude pervades across the board in creative industries. People are quickly swapped out, creations are consumed immediately and then forgotten. But saying “fuck that” and approaching your work with more intention, as VanGaalen has learned, might lead to longer-lasting and more significant creations. There are more important things, too, than the sometimes ridiculous, unreasonable, and oppressive demands of a client, or even yourself. Like family and friends. And gardening.

“I wanna figure out winter vegetables this year, and cold storage,” VanGaalen says. “Stuff that’s gonna decrease my footprint instead of just like, ‘What more can I do?’ It seems silly, but selfishly, it’s mostly for peace of mind.”

Photos by Marc Rimmer