As a photography instructor at Rhode Island Training School, a juvenile detention center in Cranston, Rhode Island, Scott Lapham had to get creative to engage his students. His classes couldn’t leave the school, so they were limited to shooting photos in tightly controlled, concrete-walled surroundings. Despite this, Lapham and his students managed to work together to create a series of deeply personal portraits that offer a window into what it’s like to be in juvenile detention in the United States.

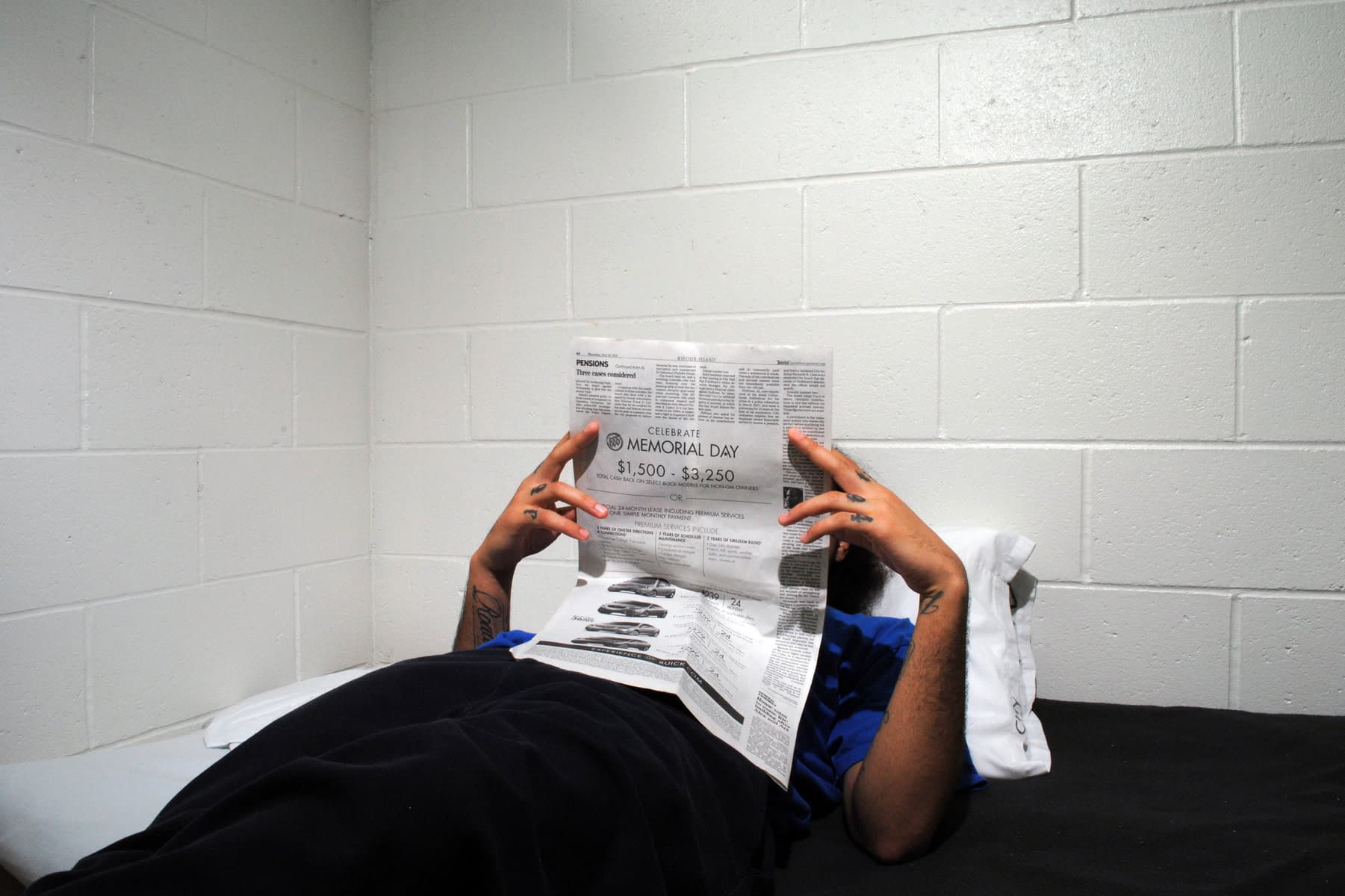

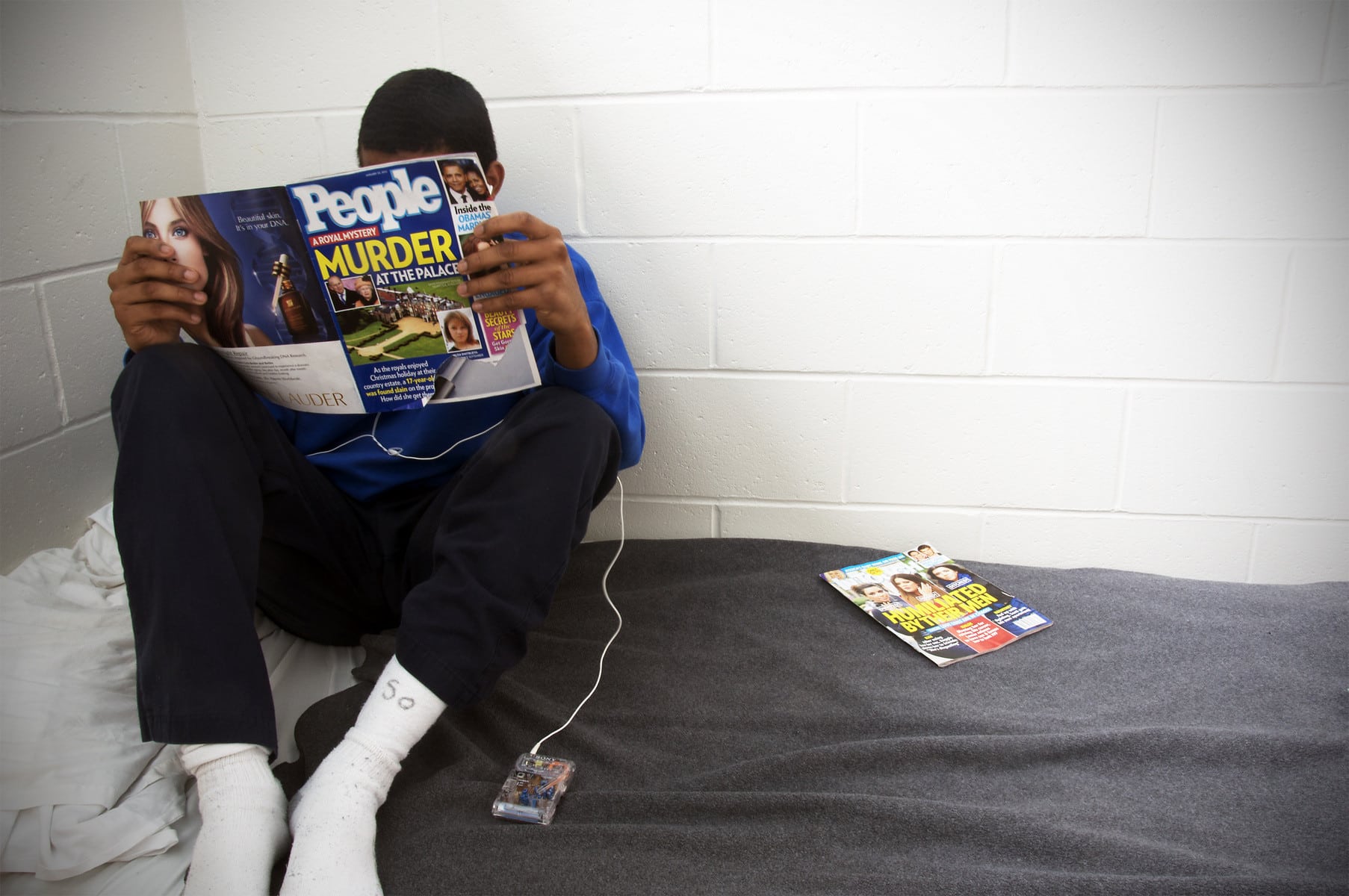

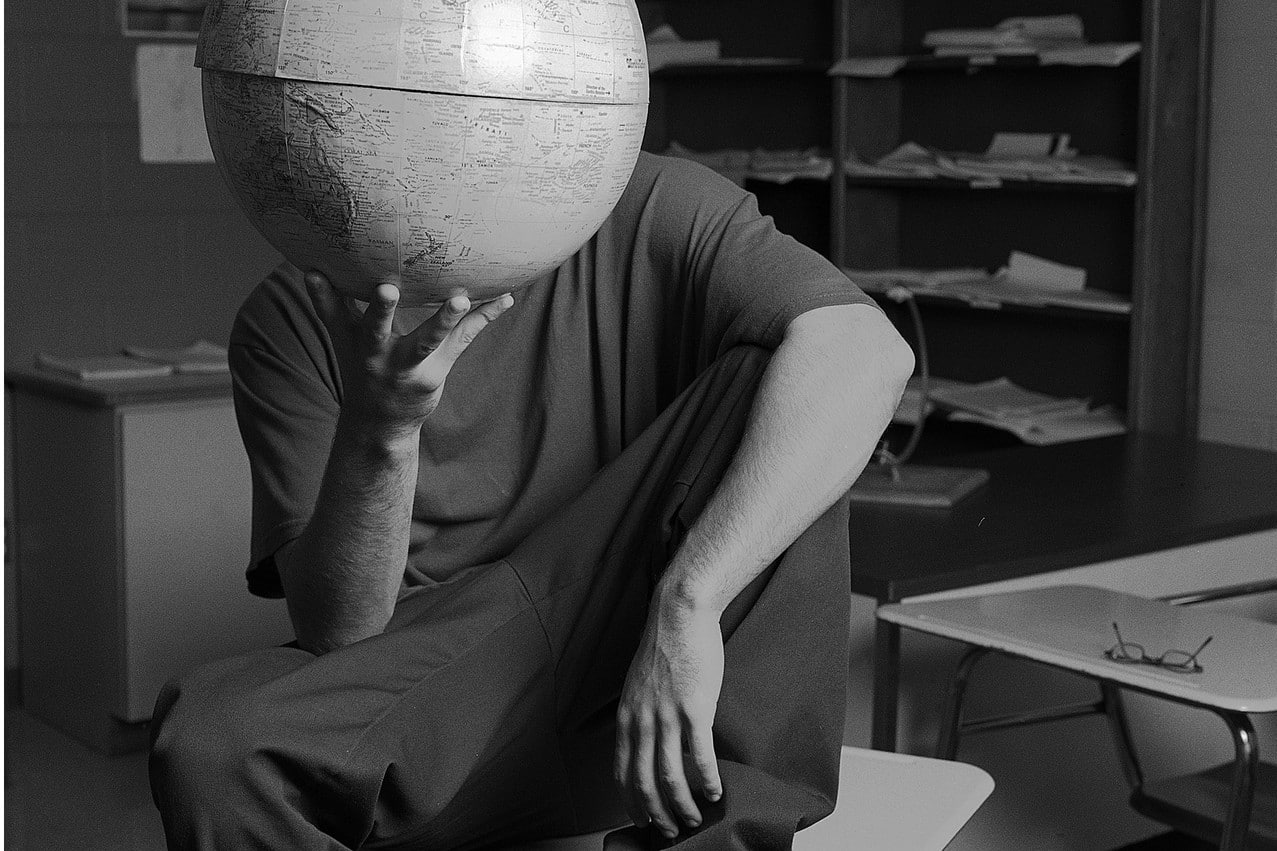

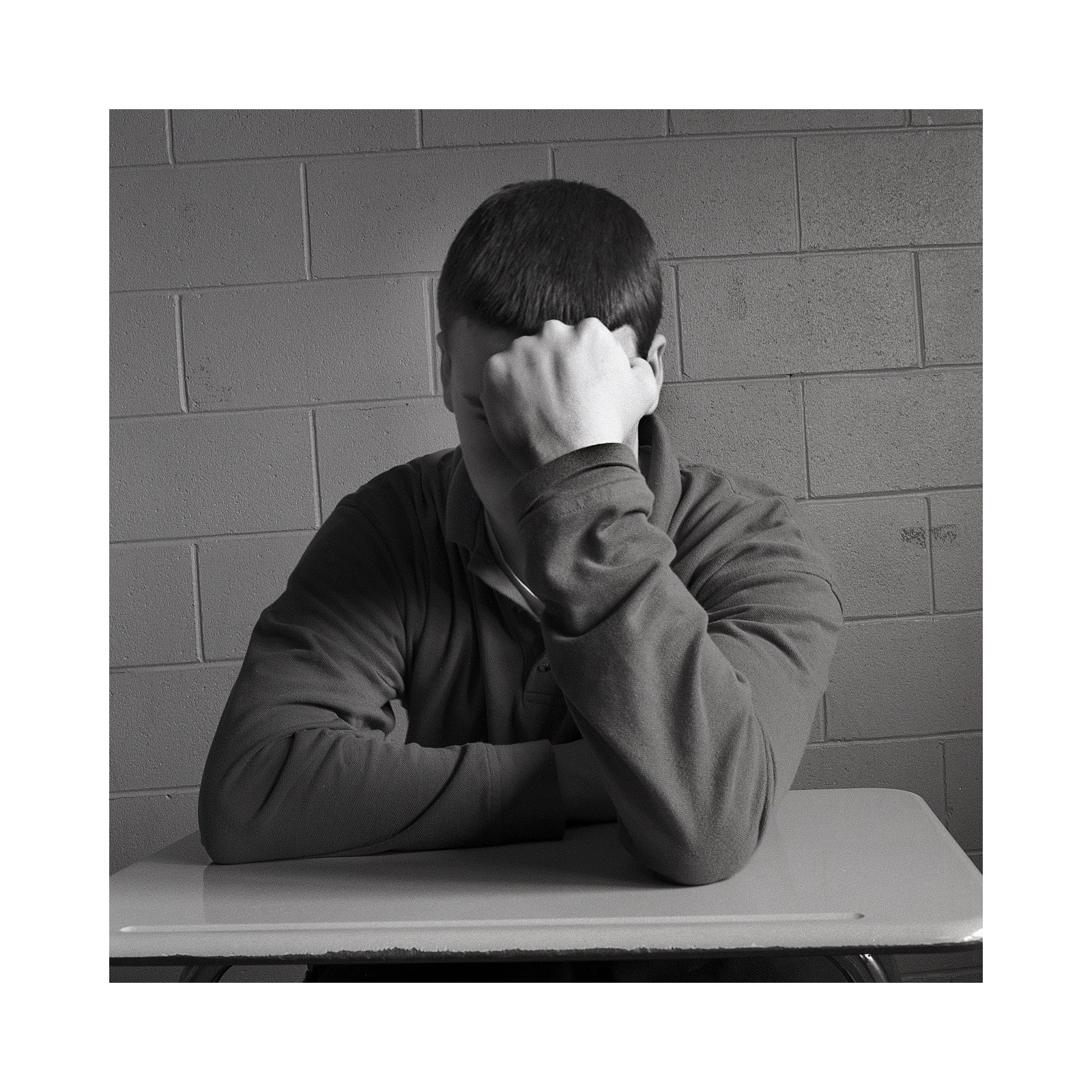

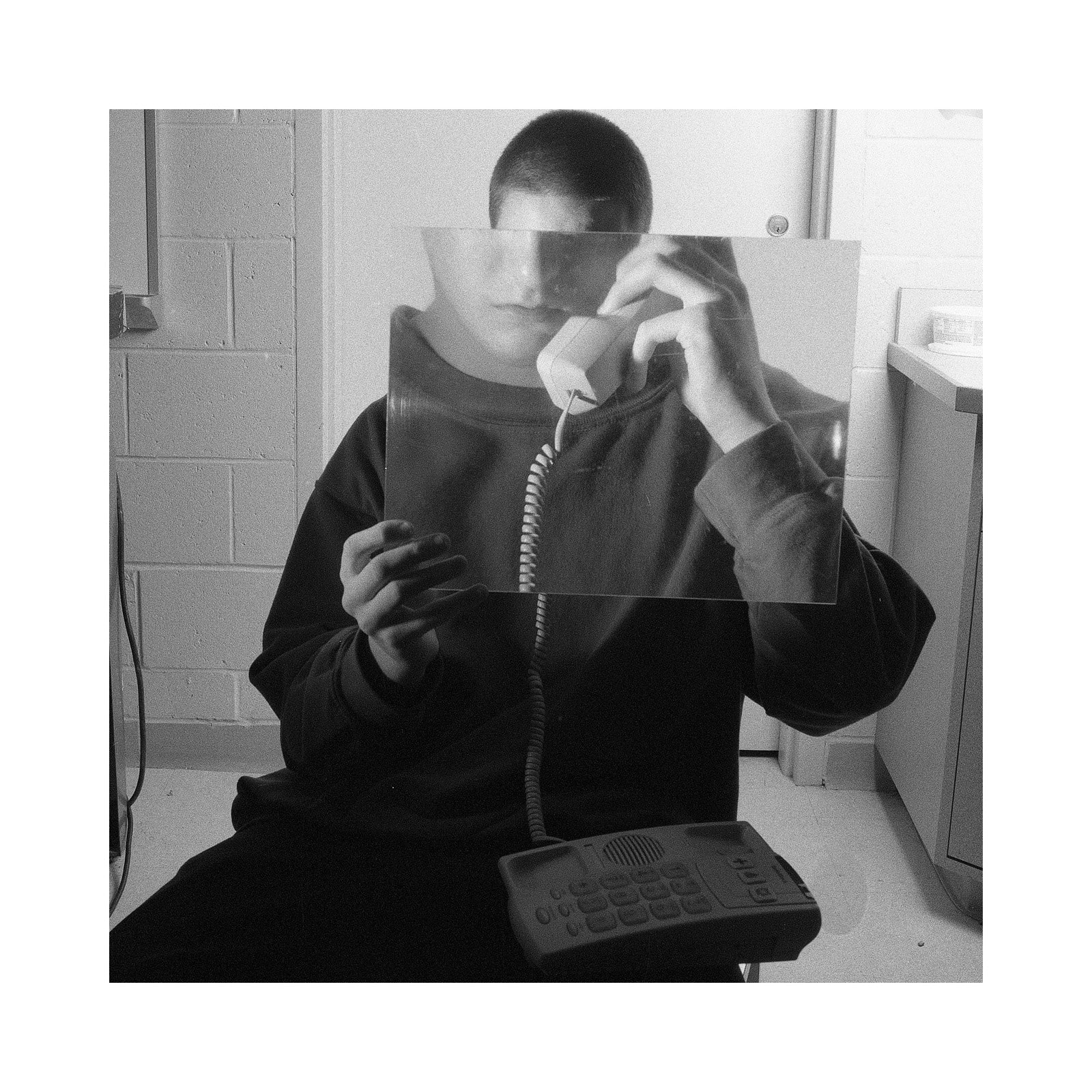

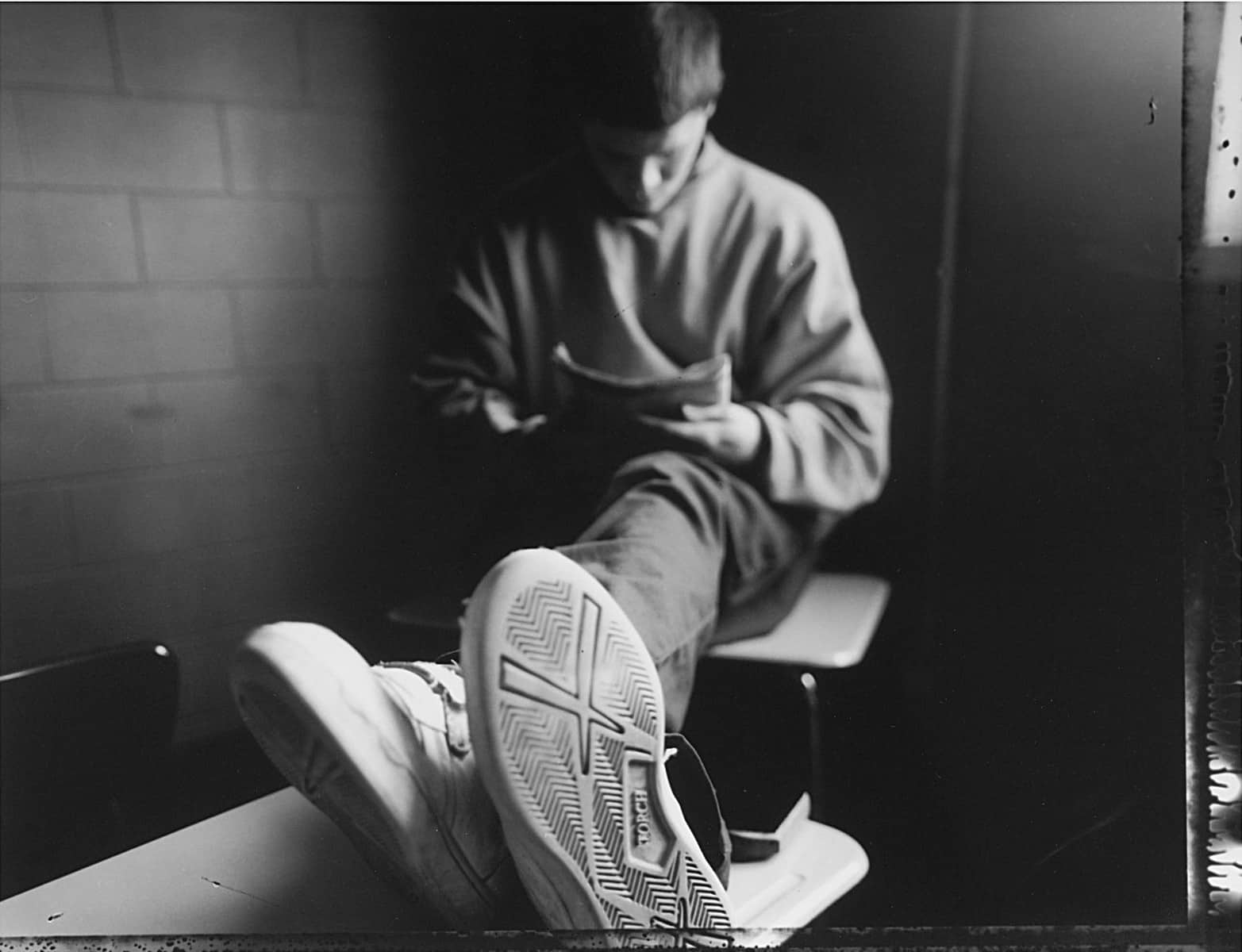

Not only were they limited to an overwhelmingly plain, institutional backdrop, but Lapham and his young photographers had to work around the fact that none of the subjects of their portraits could reveal their faces: United States law protects the identities of young offenders.

The result, which comes from Lapham’s 15 years of teaching, is a photo project that’s at turns both playful and eerie, challenging established ideas of who juvenile offenders are and how they would like to be seen. The project would likely still be ongoing if public funding for the program hadn’t run out, causing Lapham’s photography class at the Training School to be ended.

Format called Lapham in Rhode Island to talk about the challenges of teaching photography in a detention center.

Format: Could you tell us a bit about your job at the Rhode Island Training School?

Scott Lapham: The Rhode Island Training School is Rhode Island’s juvenile detention facility. So it’s a locked-down facility, with all the rules and regulations that you would expect in a youth prison.

My engagement there started in the year 2000, and it went through 2015. I was working with the AS220 Youth Program, which worked to teach incarcerated students, and also worked to be a bridge outside of incarceration, having classes at AS220’s downtown Providence studio.

The students working in the Training School are juveniles. That means, by law, we are not able to show any of their facial features or identifying marks on their body. Also, we didn’t want to do that even if we were allowed to, because we didn’t want the students’ incarceration to follow them out of the Training School.

In the United States, when you’re a juvenile, when you become an adult you can have a clean record, and that’s very important for a young person’s trajectory into adulthood. The more time spent in the legal system, the harder it is for a person to turn their life around in a positive direction. So because of that, myself and the students were really challenged to make portraits that concealed their faces.

How old were most of the students?

Students were as young as 12, and a few were in a grey area where they were technically adults but they weren’t at the adult correctional institute. So some of them were potentially as old as 20, but that was rare. Most of them were between the ages of 12 and 18.

Was the class required? How did students come to take it?

It was not required, students signed up for it on their own. A lot of it was simply that students were bored. There wasn’t a lot of stimuli outside of school. So it was curiosity, with a lot of students. Some students just wanted to find something to do.

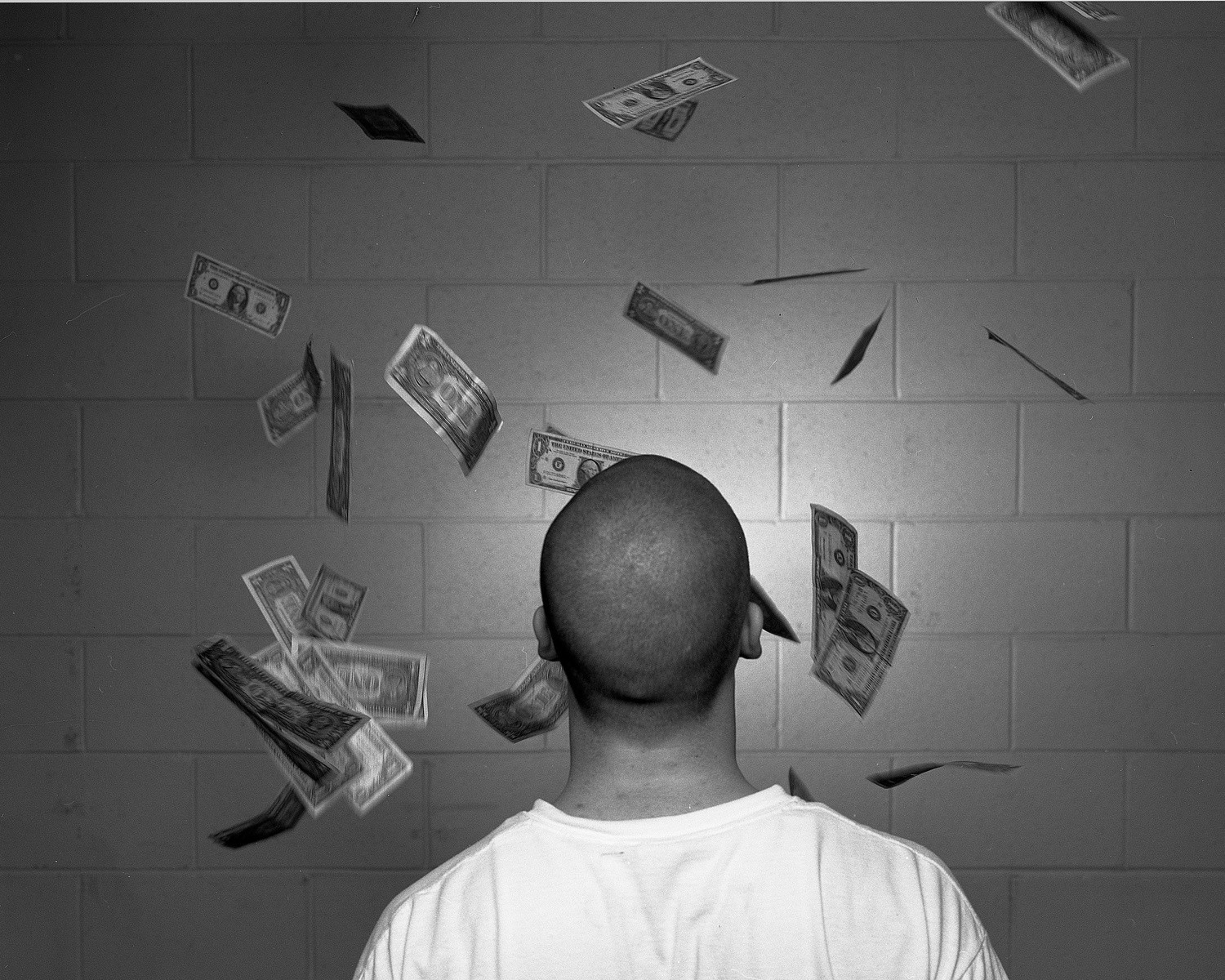

It’s a very hard place to teach, for a number of reasons. Very negative place to be. Most students are really there not because they’re bad people, but because they’re poor. The environment is negative. Learning is not encouraged. If a student is showing they’re learning, that’s often something that can be ridiculed.

There are a lot of young people that, outside of the Training School, are enemies, and then they’re confined to be with one another in very tight locations—living quarters, classrooms—so there’s sometimes tension there. And there are also an awful lot of young people that have learning disabilities and other conditions. People are at the Training School typically because something has gone very wrong in their lives. Because of all those factors, it can become a very challenging place to teach.

What kind of challenges did you experience teaching there?

I think the first challenges that I found were challenges that a lot of teachers find when they start. Things like classroom management. Not understanding the culture of the institution I was working in—both the adult and youth culture. When I started working with this population, there was less sensitivity to cultural awareness and communities of color. And I’m a white male. I learned on the job about my own white privilege.

I also learned on the job a much deeper understanding about poverty and class and race in the United States, than I had previously understood. It was experiential, it wasn’t an academic education. I started to understand that most of my students were really incarcerated because of the systems that are in place—that are subtle, but very real—that incarcerate poor people and predominantly people of color, disproportionate to the population.

I started to understand this on my own, by knowing students, and starting to realize, if I had grown up in a different neighborhood than where I did, under different financial circumstances, the probability of me being incarcerated as a teenager would have been as a high as the students I was teaching.

What do you think your students got from learning about photography?

My students, by and large, were not exposed to art-making. And if they were, it wasn’t a deep interaction. A lot of them liked the technical side of photography, a lot of them were attracted to that—in the same way that people would be attracted to musical gear, or cars, or what have you. That was an interesting way to have people be initially interested in what was being offered.

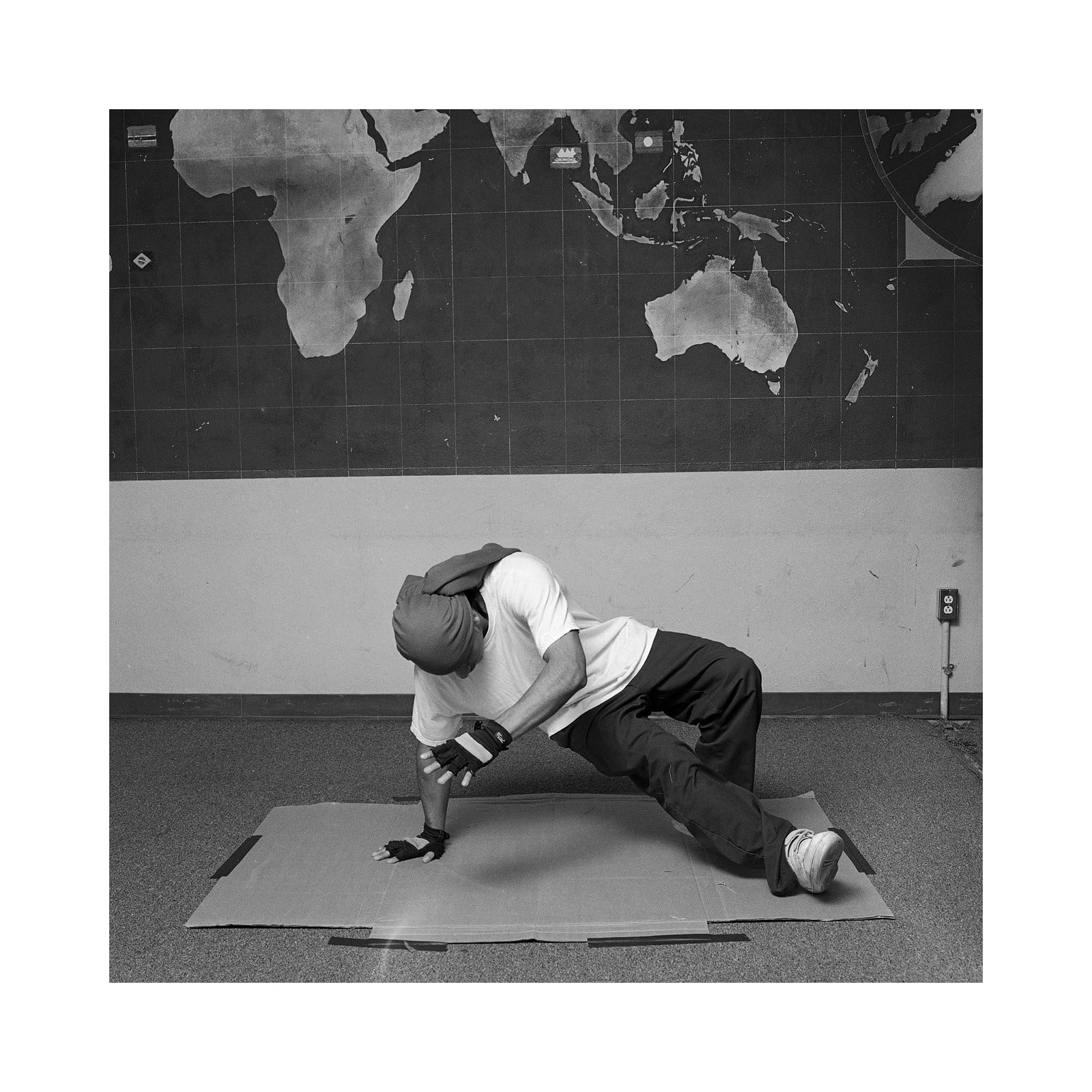

Then conversations about how one makes portraits of oneself became something of interest. All these pictures, all these photographs are collaborations of one sort or another. Sometimes I’m pressing the button, and sometimes I’m not.

I can’t give authorship to the young people that took the pictures, because it would be illegal for me to do that since they were incarcerated, and there by law can be no documentation of who is incarcerated as an individual. But I think it is important to know that I took some of the pictures, and others I didn’t.

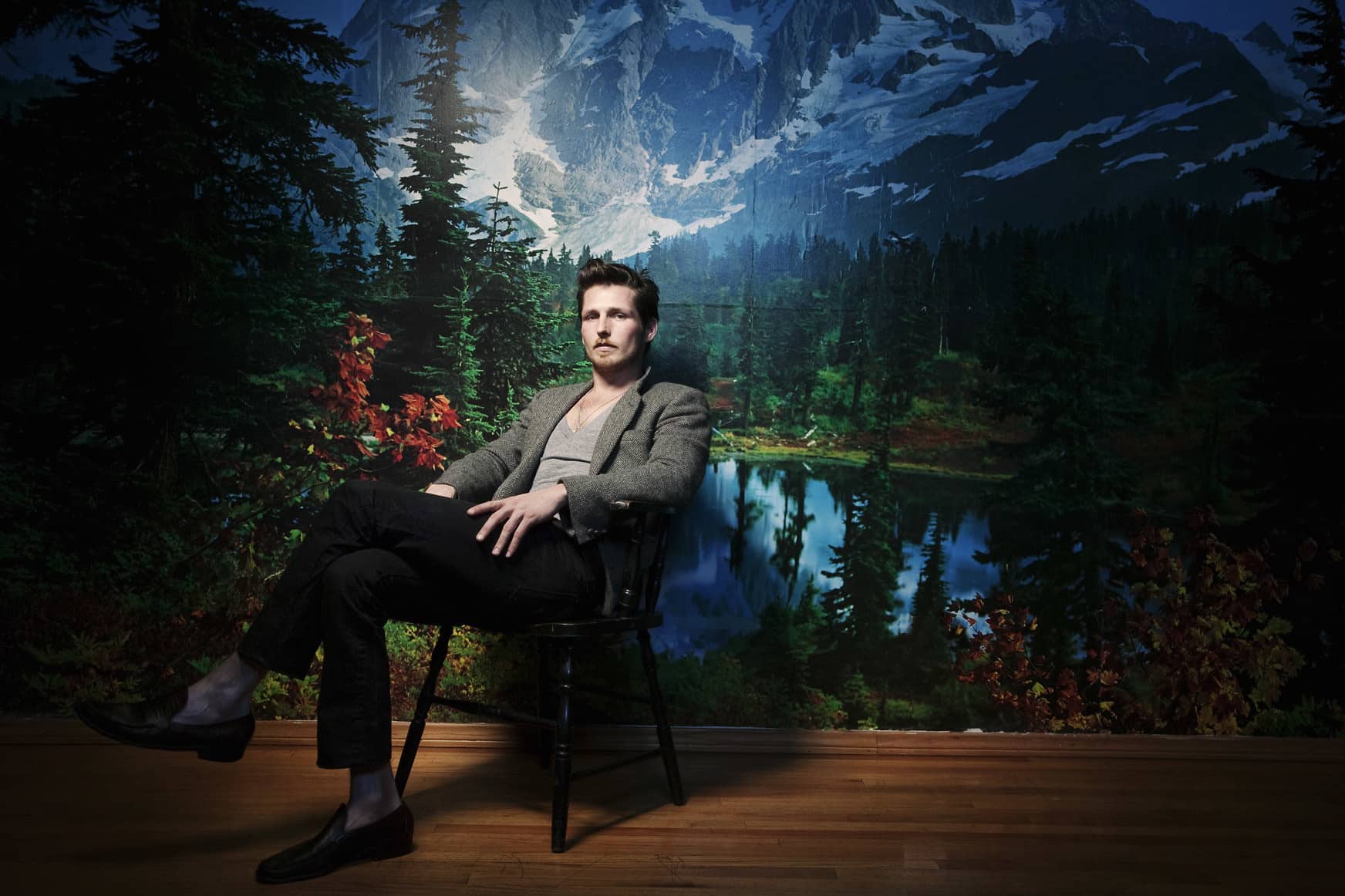

This was a chance for students to present themselves in these circumstances the way they wanted to be presented. It was a chance to talk about what we did want to show, and what we didn’t want to show.

Did we want to mimic a mug shot, did we want to mimic someone being searched as though they’re being searched by police? Those were go-to kinds of pictures that students had kind of internalized, and that were challenged. Do you want to project something different, do you want to project something more personal?

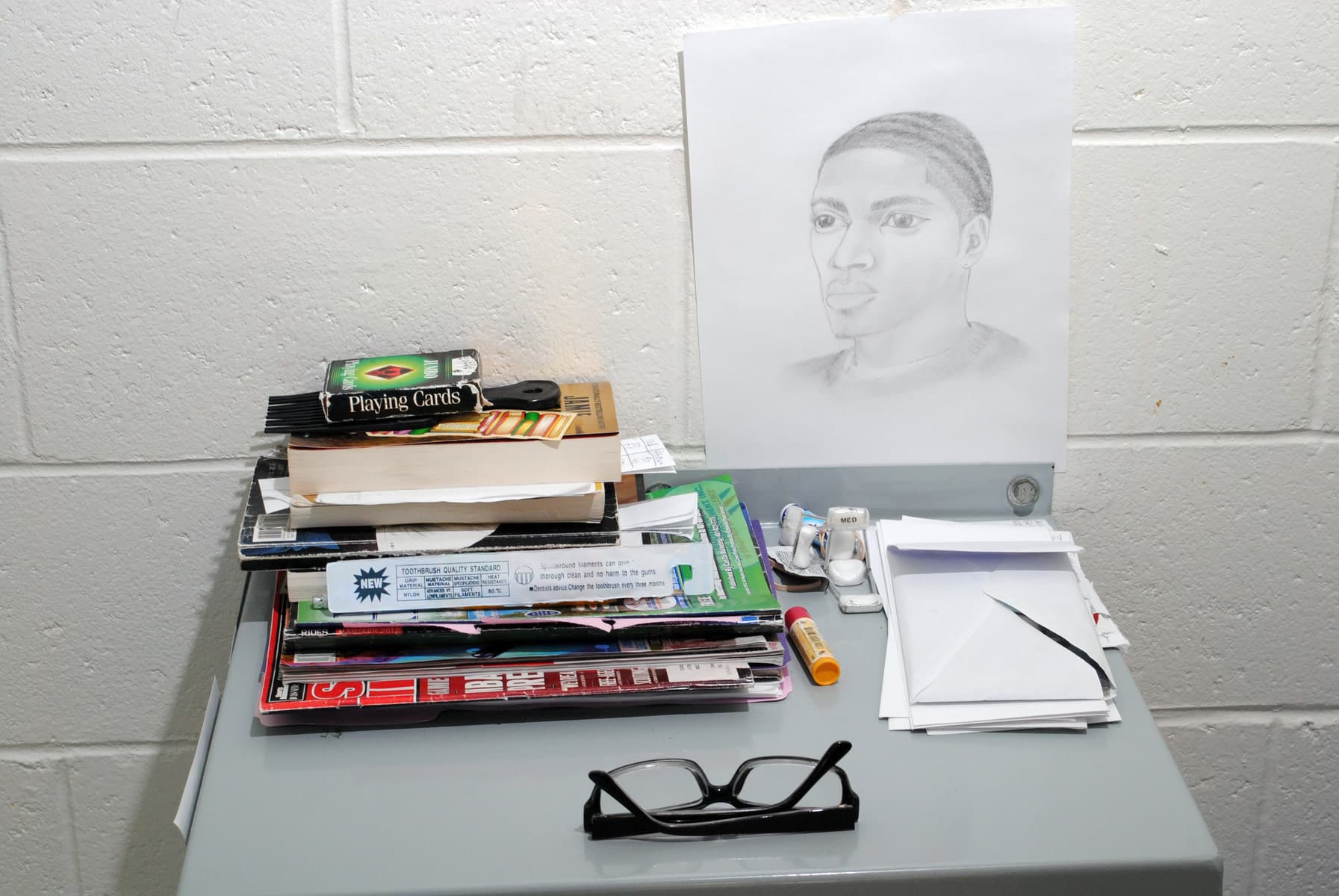

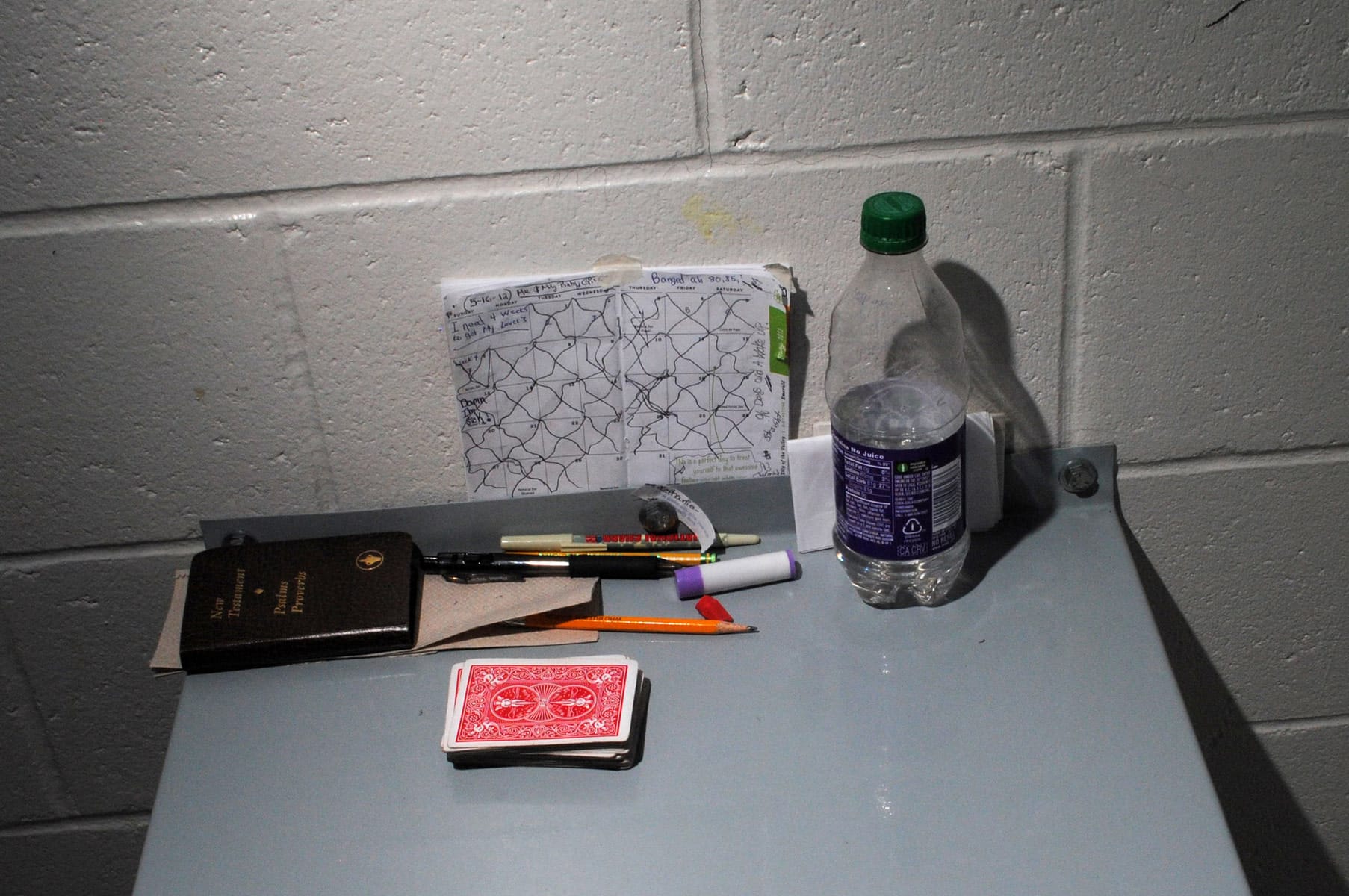

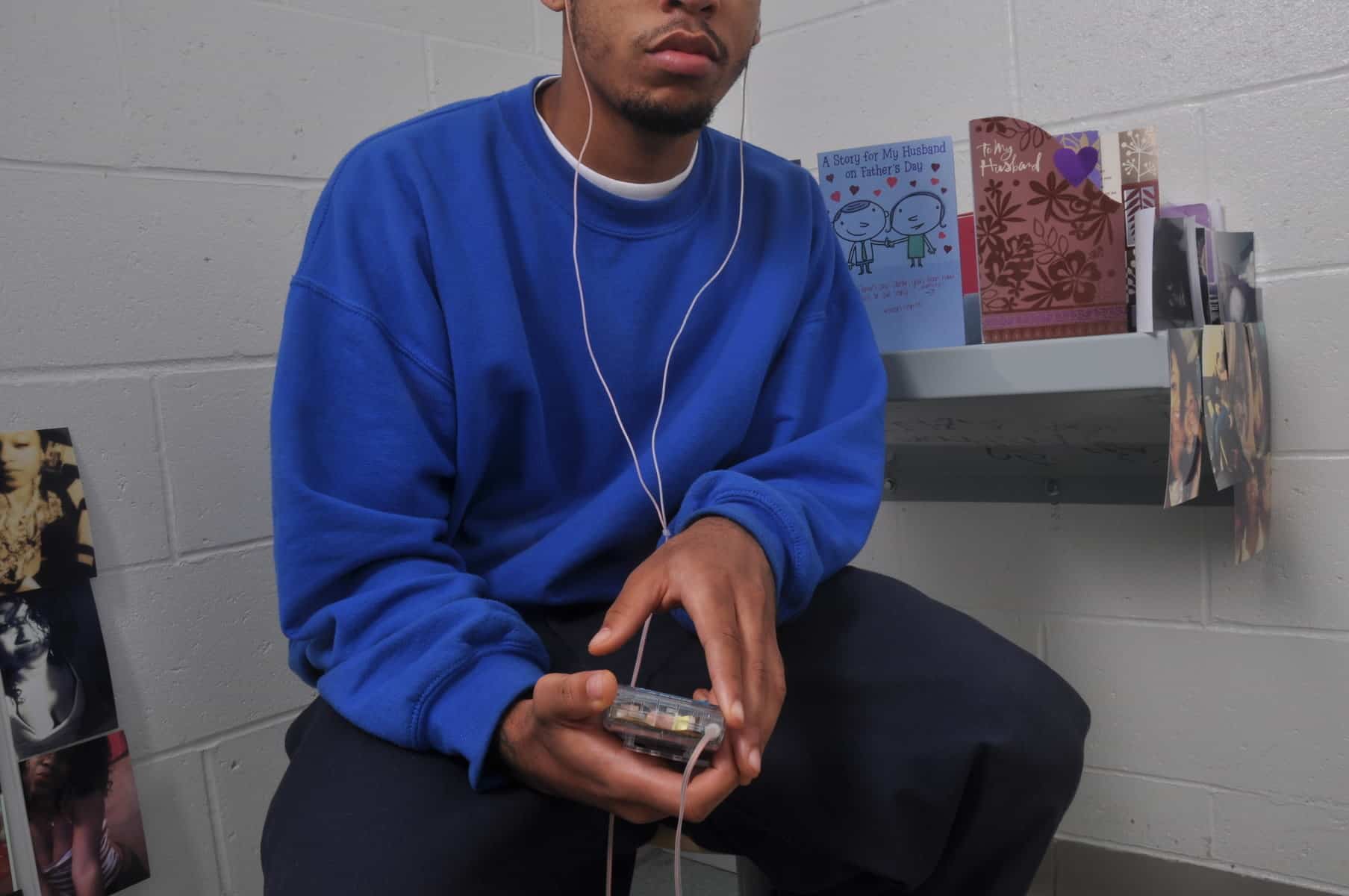

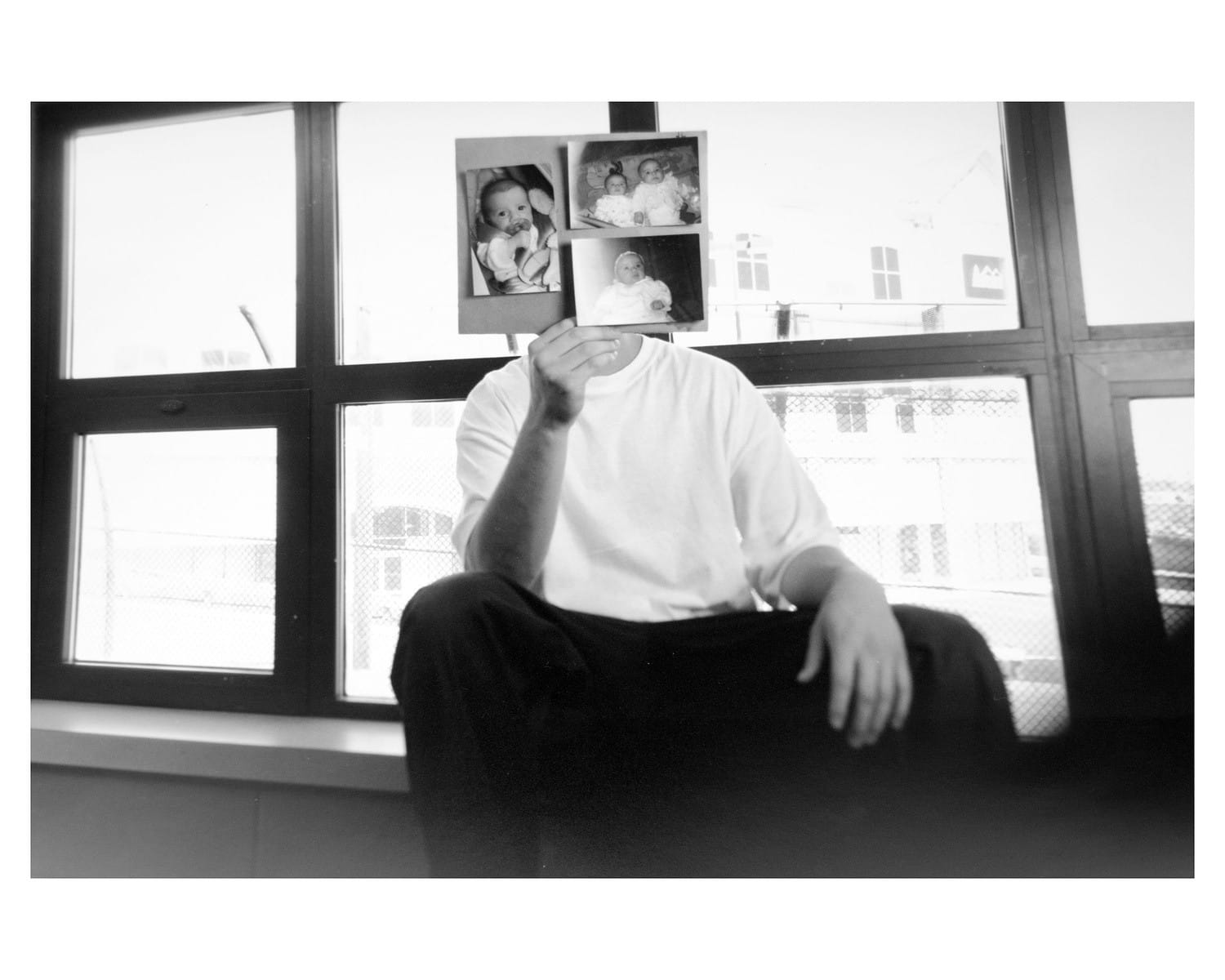

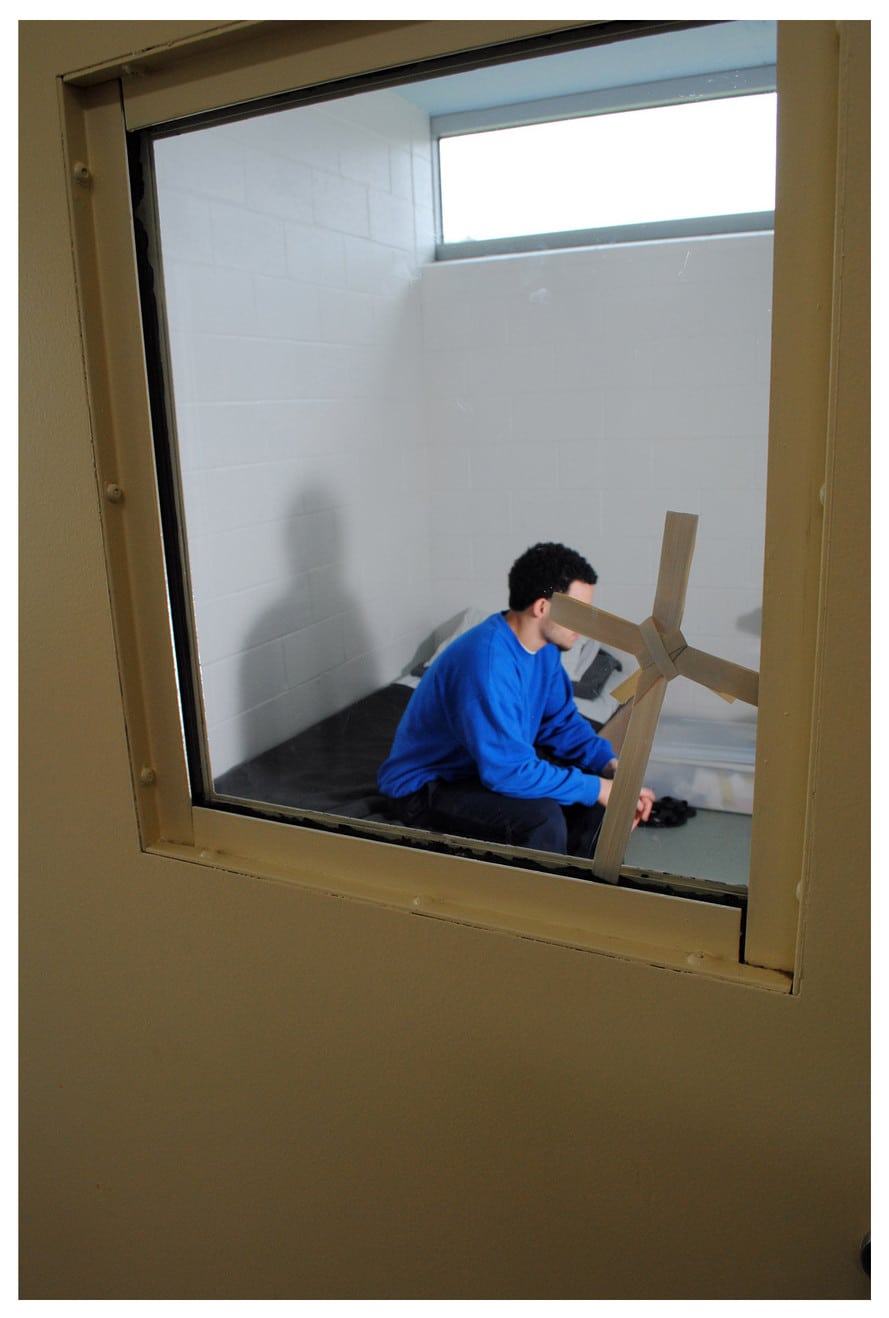

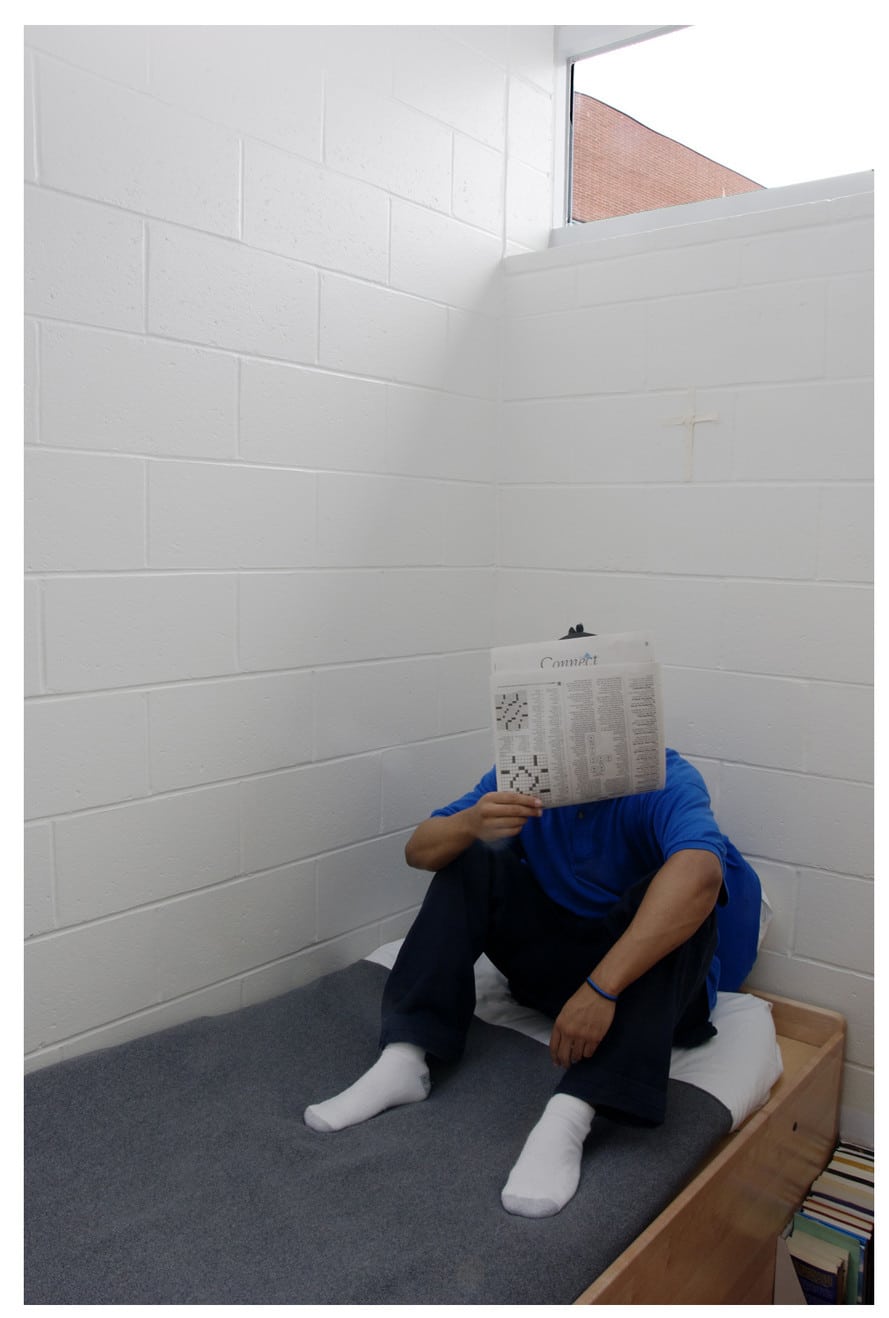

Do you want to show pictures of your baby daughter that is growing up without you, on the outside? Do you want to show picture of you as a hip hop performer? Or if we’re in your room—your room is so depersonalized, what personal in it is there for you to show? What kind of a pose do you want to have in your room?

People were very excited to have pictures in their rooms, because it was the only piece of personal space that most of them had within their incarceration. Everything else was public. And those rooms could be torn apart at any time looking for contraband or any other thing.

But most people did have some aspect of personalizing their space that they wanted to have documented in some way. It was an opportunity for young people to start creating their own narrative, and have a little bit of control over how they were presented, how they wanted to look, as opposed to having little control over circumstances.

Have you kept in touch with any of your former students?

I’ve kept in touch with a number of them. Some of them have done remarkable things. A few of them have become photographers, and that’s pretty gigantic, and goes against the odds. Some of them are incarcerated as adults. It’s a sobering reality.

A student simply escaping adult incarceration, and working towards a life of stability, is a tremendous success. There are so many challenges that young people face, that the idea of becoming a stable, happy adult is a tremendous success, and it’s on par with any other definition of success that people may heap accolades onto.

I have kept in touch with a lot of students, and some of my students who are working incredibly hard at their jobs, who are working to support children, are still friends of mine.

Others have moved from the state of Rhode Island, which is on the east coast of the US, and moved to California. And that was a tremendous success, because it means that a young person felt confident enough to leave not only a neighborhood where they’re from, but a state. And take on these big challenges in going somewhere—it’s hard for anybody, no matter what your past, to move to a completely different place, and try to set up shop and make yourself a happy, stable person.

Mehr finden von Scott LaphamArbeit in seinem Portfolio, das er mit Format.