Derrick C. Browns Weg zur Poesie war nicht gerade typisch. Anfang der 90er Jahre fand sich der gebürtige Kalifornier in einem Schützenloch der 82. Airborne wieder, einer Infanteriedivision der US-Armee, die sich auf Fallschirmsprungoperationen in abgesperrten Gebieten spezialisiert hat. Um die Langeweile zu vertreiben, las er in seiner vom Militär bereitgestellten Bibel und schrieb die Psalmen in verständlicher Sprache um.

Kurz nachdem er aus der Armee entlassen wurde und die Volkshochschule besuchte, lud ihn ein Freund ein, sich eine Gedichtshow in einem örtlichen Café anzusehen und etwas vorzulesen. "Ich las die Dinge vor, die ich in die Bibel gekritzelt hatte", sagt Brown, während er im Tourbus der Rival Sons in Toronto sitzt. "Und es war wirklich schlecht, und sie haben es akzeptiert. Das hat die Sache ins Rollen gebracht."

Seitdem hat Brown zahlreiche Bücher geschrieben und ist mit seinen Gedichten durch die Welt getourt, oft als Vorgruppe für Bands wie die Cold War Kids oder Komödianten wie Eugene Mirman und David Cross. Er arbeitete mit den schottischen Post-Rockern Mogwai in einem Video für sein Gedicht "Ein Finger, zwei Punkte, dann ich". Für seine Sammlung "Texas Book of the Year" wurde er 2013 mit dem Preis Seltsames Lichtund veröffentlichte kürzlich eine gewichtige Anthologie Uh-Ohdie eine neue Sammlung mit dem Titel "Alle Energien des Todes" enthielt. Im März veröffentlichte er eine Sammlung von Liebesgedichten mit dem Titel Wie der Körper die Dunkelheit verarbeitetdie liebenswerten Witz, clevere Frechheit und herzergreifende Emotionen miteinander verbindet. Eine Kombination, die Brown seit den ersten Tagen im Coffee Shop verfeinert hat.

Hier in Toronto machen ihm jedoch Allergien und Flugreisen zu schaffen. "Wegen meiner Nebenhöhlen funktioniert nur eines meiner Ohren", sagt er. Obwohl es so aussieht, als wäre er durch die Luft in Nashville ziemlich geschwächt, ist Brown warmherzig und gesprächsbereit. Dies ist der einzige kanadische Termin der Tournee, und kurz nach Mitternacht, wenn die Ausrüstung abgebaut, die Hände geschüttelt und die Bücher im Anhänger verstaut sind, macht sich die ganze Band auf den Weg nach Detroit.

Brown sagt, dass dies bis jetzt eine der besten Touren seines Lebens war. Die Termine in den USA waren unglaublich gut besucht. Aber in Europa war es ein bisschen anders.

"Es war einfach schwer", sagt Brown. "Der Versuch, Menschen aus Nordfrankreich für englische Lyrik zu begeistern und den Humor, die Kraft und die Gleichnisse zu verstehen, kann ein Krieg sein, besonders wenn sie Englisch lernen wollen. Und ich kann kein Französisch. Ich dachte, Polen würde hart sein und es war großartig. Ich dachte, Italien würde hart sein, aber es war so gut, und sie haben mitgesungen. In manchen Städten wie Frankfurt haben sie mit Scheiße nach mir geworfen, zum Beispiel mit Bierbechern. Und in Kopenhagen haben sie versucht, mich von der Bühne zu pfeifen. In München gab es eine Menge Zwischenrufe. Bestimmte Städte, in denen ich in der Vergangenheit viel Glück mit Poesie hatte, waren einfach hart, weil es ein Rock 'n' Roll motiviertes Publikum war."

Aber das Touren ist ein wichtiger Teil dessen, was es 2017 möglich macht, als Dichterin oder Dichter seinen Lebensunterhalt zu verdienen. Und selbst dann wird es natürlich nicht einfach sein. "Du musst entweder an einer Universität unterrichten oder für eine gemeinnützige Organisation arbeiten und von ihr bezahlt werden, wie Beleuchtet werden oder Lauter als eine Bombediese Jugend-Poesie-Sachen", sagt Brown. "Oder du musst auf Tournee gehen. Oder du musst in irgendeiner anderen Sache berühmt werden, wie ein Schauspieler oder Musiker oder Sportler, und dann ein Buch herausbringen. Dann kannst du deinen Lebensunterhalt verdienen. Aber du verdienst deinen Lebensunterhalt bereits auf andere Weise."

Und das Touren ist sicherlich kein Zuckerschlecken. Stephen Lattys Dokumentarfilm Du gehörst überall hin begleitete Brown und die Cold War Kids Ende der 00er Jahre auf ihrer Europatournee und zeichnete viele von Derricks Auftritten sowie einige der Höhen, Tiefen und Zwischentöne der Reise auf. Brown sagt jedoch, dass die Doku letzteres besser beleuchtet hätte und wünscht sich, dass sie mehr Zeit für "die Seltsamkeiten zwischen den Auftritten, die Einsamkeit nach den Auftritten und die Langweiligkeit, acht Stunden im Bus zu sitzen" gehabt hätte.

"Es wurden viele Gedichte gezeigt, aber was mich interessiert, sind die Zwischenrufe, das Geschrei, die Gespräche mit den Fans, die Umarmungen, die intimen Geschichten der Leute... Ein bisschen davon wurde gezeigt. Die Gedichte in voller Länge haben mich nicht so sehr interessiert. Ich wünschte, es wäre dokumentiert worden: "Hier ist ein Künstler, der etwas ausprobiert, von dem er nicht weiß, dass es jemals zuvor jemand gemacht hat."

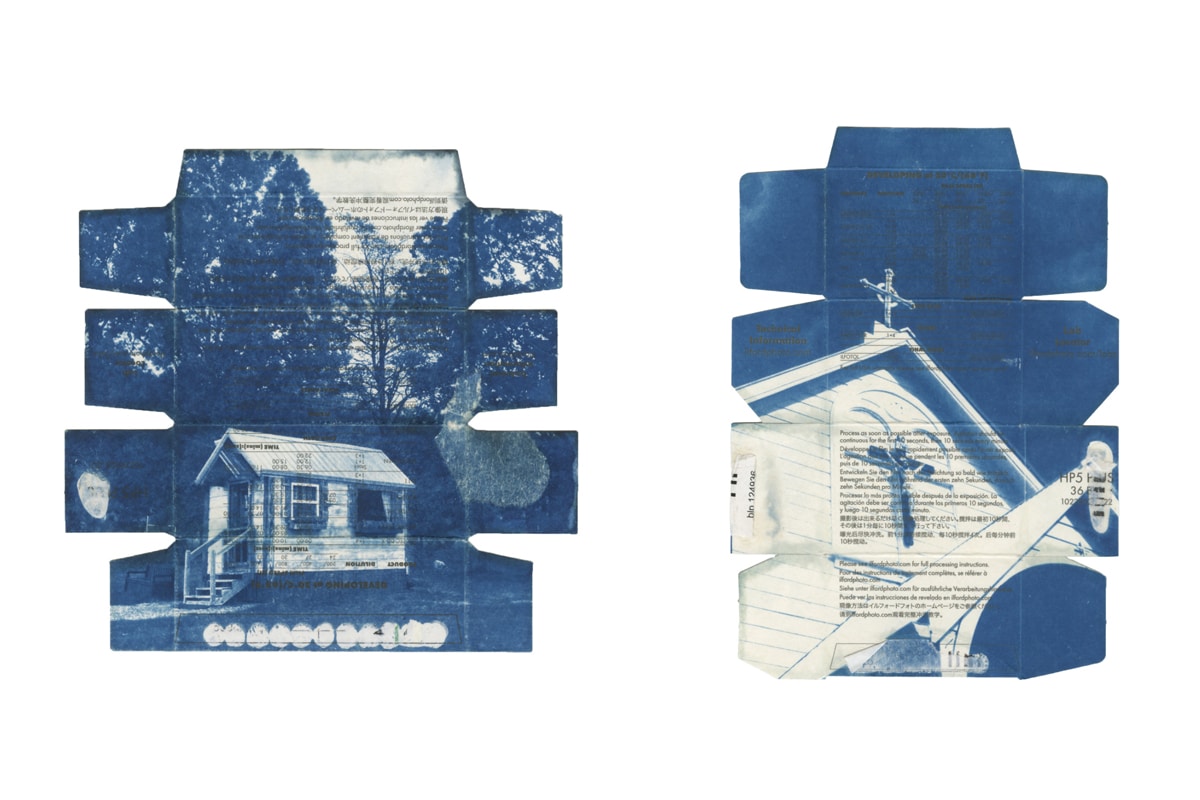

Am Ende des Dokumentarfilms gibt es ein Interview nach der Tournee, das zeigt, dass Brown seine eigene Presse hat, Write Bloody Publishingein Unternehmen, das "mit einer Lüge begann". Er brauchte Bücher für seine erste Deutschlandtournee, aber keine der Druckereien, in denen sie veröffentlicht wurden, konnte ihm damals welche liefern, also beschloss er zu versuchen, sie selbst zu drucken. Die Preise, die ihm genannt wurden, machten diesem Gedanken jedoch schnell ein Ende. Schließlich fragte ihn eine Presse in Ohio, ob er ein Verleger sei, da sie Verlegern ermäßigte Preise gewähren. Er sagte zu, dass er zurückrufen würde, und bat seinen Freund, schnell eine Website für Write Bloody - den Slogan seines Tour-T-Shirts - mit ein paar gefälschten Buchcovern zu erstellen.

"Und es hat funktioniert", sagt Brown. "Als ich dann auf Reisen war, traf ich andere Dichter wie Buddy Wakefield die ziemlich hässlich aussehende Bücher hatten. Ich sagte: "Mann, wenn du eine ISBN und ein hübsches Buchcover bekommst, zahlen die Leute $15 für dein Buch, und statt $3 pro verkauftem Buch kannst du $9 verdienen und viel leichter von Tourneen leben.

"Der einzige Weg, Bücher zu verkaufen, ist auf Tournee zu gehen. Wenn ein Autor oder eine Autorin gut sprechen kann, ohne dass man sich unwohl fühlt, wenn er oder sie auf der Bühne steht - keine singende Stimme, sondern eine echte Verbindung zum Publikum - und wenn er oder sie dann auch noch gut schreiben kann, sollten wir ihm oder ihr ein schönes Buch geben. Und dann können sie auf der Straße besser leben."

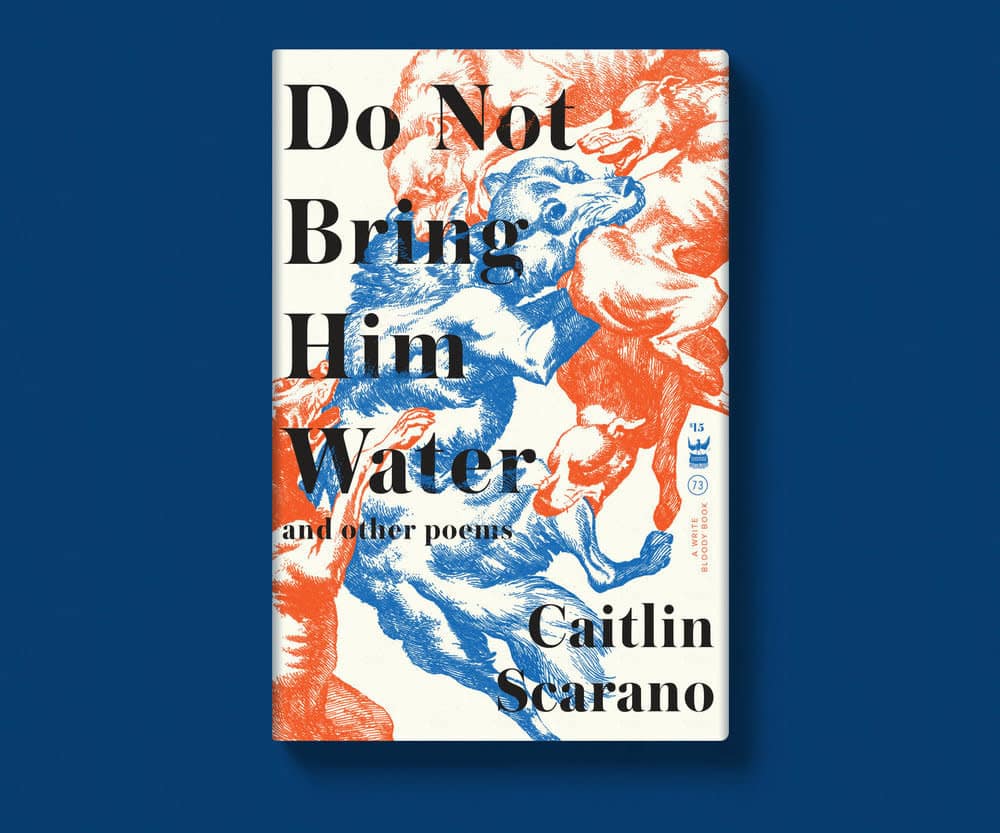

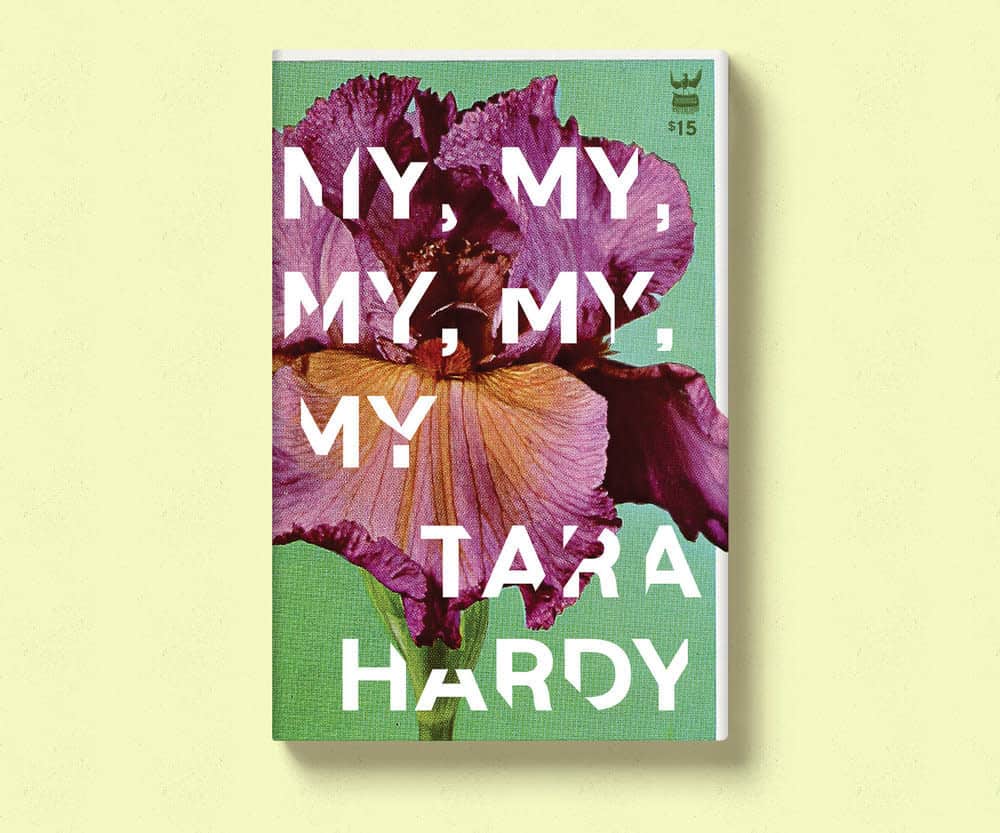

Bücher von den Write Bloody-Dichterinnen Caitlin Scarano und Tara Hardy.

Seitdem lautet die Leitphilosophie von Write Bloody: "Lass die Dichter und Autoren, die auf Tournee gehen, das Marketing sein; lass diesen Verlag die Quelle für eine Bewegung sein." Brown besteht darauf, dass das Wichtigste die geschriebene Seite ist, aber die Dichterinnen und Dichter, die am besten in der Lage sind, aufzutreten und eine echte Verbindung zu ihrem Publikum herzustellen, sind diejenigen, die die meisten Bücher verkaufen.

Das Verfahren, mit dem sie entscheiden, wer diese Dichterinnen und Dichter sein könnten, ist ziemlich gründlich. Während der jährlichen Einreichungsphase im Juli reichen die Autorinnen und Autoren fünf Gedichte ein. Wenn diese fünf Gedichte gut ankommen, werden sie um weitere 20 gebeten. Und wenn sie es in die Endrunde schaffen, werden sie gebeten, ein Video von ihrer Lesung zu schicken. Wenn sie gut lesen - ohne alberne, aufgesetzte Allüren oder melodramatisches Getue -, reichen sie 40-50 Gedichte ein und legen einen Veröffentlichungstermin für das nächste Jahr fest. Von dort aus feilen sie mit Redakteuren an ihren Werken.

Browns Wurzeln in der Independent-Musik sind tief verwurzelt, und Write Bloody stellt den Autorinnen und Autoren ein sogenanntes "Monsterpaket" zur Verfügung, in dem sie lernen, wie man eine lustige Buchveröffentlichungsparty veranstaltet (wie eine Plattenveröffentlichungsparty) und eine Pressemappe erstellt. Das klingt nach einer Familienangelegenheit: Diejenigen, die in der Bewerbungsrunde 2016 ausgewählt wurden, bekamen ein spezielles Ankündigungsvideo, in dem sie zu Drake tanzen und die Botschaft "Willkommen zu Hause" verkünden.

In Browns eigenen Gedichten findet sich eine ähnliche Wärme - eine oft ergreifende Kombination aus elektrischer Sprache und Leidenschaft, die von unreifer Heiterkeit bis hin zu kosmischer Tiefe reicht, meist im selben Stück. Bei seinen Lesungen wird er von Musik begleitet, meist von Freunden oder von Bands, die er gebeten hat (darunter Kevin Drew von Broken Social Scene). Aber es hat eine Weile gedauert - und eine gewisse Anleitung - um von diesen frühen umgeschriebenen Psalmen zu der Stimme zu kommen, die er jetzt hat.

"Damals dachte ich, wenn es seltsam oder bizarr ist, ist es Poesie, ist es Kunst", sagt Brown. "Und ich war super esoterisch und surreal, ohne Bodenhaftung oder Ernsthaftigkeit im Gedicht, nichts, womit man es verbinden könnte. Ich dachte, es ginge nur um Wildheit, und ich hatte keine Lust auf Lektorat, Workshoppen oder Tippen. Und ich habe mein Publikum und meine Leser irgendwie im Stich gelassen. Ich konnte mir nie vorstellen, dass jemand ein Chapbook oder ein Buch kauft. Ich dachte mir: "Ich gehe einfach hin und zeige, dass ich kreativ bin! Ich dachte, das wäre alles, was ich brauche. Aber eigentlich sehnte ich mich nach einer Verbindung, und erst durch das Bearbeiten und Abtippen dieser Gedichte wurden die Verbindungen am stärksten."

Er schreibt auch dem Dichter Jeffrey McDaniel als eine wichtige frühe Inspiration und ermutigende Kraft in seiner Entwicklung als Dichter, jemand, der ihm helfen konnte, den Nutzen und die Kraft der Poesie zu lernen. Aber auch seine Zeit bei der 82. Luftlandedivision, die "mich dem Tod nahe brachte und mir die Angst vor dem Tod nahm", wie er sagt, hat sein Werk geprägt.

"Das Zusammentreffen all dieser verschiedenen Menschen und ihrer Ideale beim Militär half mir, aus vielen religiösen Vorstellungen herauszutreten, in denen ich gefangen war, und gab mir eine Insider-Perspektive darauf, wie das Militär funktioniert und was daran schön und was beschissen ist. Das gab mir ein gewisses Gleichgewicht."

Wenn das alles ein Bild von jemandem zeichnet, der nicht in die traditionelle Vorstellung von einem Dichter passt - die Romantiker mit Rüschenhemd von gestern oder die Beatniks, die Däumchen drehen und auf Inspiration warten - dann liegt das daran, dass Derrick Brown überhaupt nicht in diese Klischees passt. Die meisten Dichter tun das auch nicht.

"Wir haben einen harten Kampf vor uns, um das Image der Poesie als masturbatorische Kunstform abzuschütteln, die nur für Literaten und Akademiker und nicht für die Arbeiterklasse geeignet ist", sagt Brown. "Das bedeutet nicht, dass sie dumm ist, es bedeutet nur, dass es schwieriger ist, einen Dichter zu finden, den man mag, als eine Band, die man mag. Also bin ich auf einer Mission, um zu sagen: 'Es gibt sie da draußen, und ich möchte sie mit euch teilen, durch meine Presse, durch meine Reisen.'

"Wenn ich mit einem Comedian auf Tournee gehe, sagt der Comedian: 'Okay, als Nächstes haben wir einen Dichter', und alle lachen. Und dann sagen sie: 'Nein, nein, der kommt nicht mit einer Baskenmütze raus. Keine Streifen, kein Rollkragenpullover. Er ist ein echter Dichter, und normalerweise hasse ich Gedichte. Ich glaube, du wirst ihn mögen.' Das ist die beste Bestätigung, wenn jemand danach sagt: "Ich hasse Poesie, aber heute Abend hat es mir gefallen. Du dachtest, du hasst Lyrik, aber du hattest einfach noch nie jemanden gelesen, mit dem du dich identifizieren konntest. Aber es ist da draußen. Und es gibt mehr gute Sachen da draußen als je zuvor."

Als Brown ein paar Stunden später die Bühne betritt, ist das Publikum rüpelhaft, halb in der Tüte und nicht besonders an Poesie interessiert. Es gibt einen bestimmten Zwischenrufer, einen schmierigen, langhaarigen Jungen, der aussieht, als wäre er nur heute Abend als Leihgabe aus der Vorstadt in der Stadt, der sich weigert, den Mund zu halten. Es ist ein harter Auftritt, aber Brown ist sanft und unnachgiebig - seine Fähigkeit zur Hoffnung und zum Optimismus scheint meist bodenlos zu sein - und kämpft weiter. Das letzte Gedicht, das er vorträgt, heißt "Chrome Hotel" und handelt von einem einsamen Mann, der darauf wartet, dass die Frau, die er zuvor kennengelernt hat, auf sein Zimmer kommt. Das Gedicht beginnt sanft und steigert sich, ohne zu viel zu verraten, in den letzten Minuten zu einem explosiven, lasziven und atemlosen Finale. Es fühlt sich an wie ein Triumph der Poesie bei einer Rock 'n' Roll-Show.

In der Bar nach der Show, umgeben von ein paar Freunden und Fans, sitzt Brown in einer Kabine und ist sichtlich erschöpft von den Allergien, die ihn geplagt haben, und von dem Kampf, den er mit einem Publikum führen musste, das für Riffs gekommen war und stattdessen eine Lesung bekam. Aber mehr als einmal schaut er in die Runde und sagt: "Das ist mein Lieblingsteil des Abends".

Die Messlatte war vielleicht etwas niedrig angesetzt, aber er schätzt die Verbindungen, die mit dem einhergehen, was er tut - sein Herz in der Öffentlichkeit ausschütten - ganz klar. Gegen Ende des Abends, bevor er in den Bus nach Motor City steigt, schließen alle die Augen, halten ihr Getränk in die Luft und er trägt das Ende seines Gedichts "Church of the Broken Axe Handle" vor. Die Kraft der Poesie wird in den letzten Zeilen deutlich: "Du kannst nicht aufgegeben werden - du kannst nur befreit werden.