Talking to the team of freelance photojournalists that teamed up to create visual documentary experiences and caught the attention of Die New York Times.

Freelance photojournalists Chris Gregory, Natalie Keyssar, und Jake Naughton cover Puerto Rico, Venezuela and LGBT issues respectively. But after spending the majority of their careers working alone, the three decided to join forces with designer Alejandro Torres Viera to create a new collaborative method of documenting and disseminating visual stories.

Their hope is that, with greater control over the creative process, they will be able to experiment with innovative technique and finally give underrepresented stories the attention and time they need.

Recently, their cooperative called Black Box was featured on Die New York Times “Lens” blog for work about Dilley, Texas, the home of the USA’s largest immigration detention center.

Blinzeln’s Laurence Cornet talks to three of the members about their visual documentary projects and the benefits of working together.

As a cooperative, one of our primary interests is in tackling stories that might not be very easy to photograph.

Laurence: How did the group come about?

Chris: We had all individually thought about some version of this collective-cooperative idea. For me, it was about transitioning from the traditional ‘lone photographer’ to a group setting where I could feed off other creative energy.

Jake: We wanted to explore ways of making pictures that were presented differently from other news media. By taking ownership over the creative process, we could experiment with less traditional and more ambitious types of imagery.

Natalie: What’s really important to all of us is to retain control of what we put out. Before Black Box, we didn’t have this kind of control. All of us did many more projects and went far more in depth than what ultimately got published. We spend time getting to the roots of the stories that we’re interested in, only to have little to no say for what is included.

So the way it works is that you work on both individual and collective projects? Can you talk about the collective part?

Natalie: We have done one pilot project together called, “Welcome to Dilley”, which we unveiled at Photoville in September 2015. It’s an exploration of Dilley, Texas, which is home of the largest woman and child detention center for immigrants in the country.

As a cooperative, one of our primary interests is in tackling stories that might not be very easy to photograph. The idea of immigrant detention in the U.S., conceptually, is much bigger than people crossing a river; in order to capture it in its entirety, we needed to get our entire team on the ground.

Chris: What makes Black Box different from other collectives is that we don’t solely work individually in the way, say, a photo agency does. A Black Box project normally has a group of artists, producing at once, who work towards a shared creative vision. The group doesn’t necessarily have to be photographers. Alejandro, who is the designer, is a large part of the process.

Jake: Going back to the genesis of “Welcome to Dilley,” we wanted to take on projects that were not obviously photo projects. Meaning that we wanted to tackle a story that had a lot of news value, but that maybe hadn’t been tackled with the depth and the visual experimentation that we were looking for.

When we went to Dilley on our first trip, to see what was there, it quickly became clear that the story was as much about the town of Dilley, Texas, as it was about the detention center itself.

So, in addition to photographing people who had been detained and documenting their stories, we spent a significant amount of time exploring the town. We set out what our roles would be in terms of whose skill sets were most productive to deploy in which manner. Chris photographed a lot of artifacts and formal portraits. Natalie did what I always feel like calling experimental reportage. And I did a lot of reporting, interviewing, and some video.

How do you end up merging different styles into a single piece?

Jake: This is where the designer comes in. When we came back and looked at our assets and laid them together we had a pretty disjointive, but thorough documentation of an immigration story. The designer helps us to organize these separate bits graphically, so that story reads as a whole.

Natalie: Alejandro, our designer, came with us on our first reporting trip to Dilley, which is a really important part of our philosophy. We want design to be inspired by our experience of the place and not to happen after the fact. We’re asking our designer to participate in research, in content exploration. We’re discussing with him what he wants and what he envisions as soon as we start thinking of the subject matter.

we wanted to tackle a story that had a lot of news value, but that maybe hadn’t been tackled with the depth and the visual experimentation that we were looking for.

How did distributors respond to your project? What happens, for example, when they have their own design team?

Natalie: The response to this work has been really positive and encouraging. Thus, so far the Economic Hardship Reporting Project has supported Welcome to Dilley, and it’s been published by Die New York Times “Lens” blog with a few more partnerships in the works and our own freestanding site.

Of course, it’s a new model. Publications have shown a lot of interest—but some haven’t been quite sure how to integrate us into their system yet. We don’t totally fit the pre-existing templates for freelance photographers out there, and that can cause some furrowed brows, but that’s sort of what we set out to do.

If they have their own design team, the idea is, ‘more heads are better than one’. They can collaborate with our designer, or divide and conquer design elements of the project. For the most part, publications are as excited about the possibilities as we are.

When editors realize that we have professional writing, video, photo and design skills and a great deal of experience in the documentary and journalism world, all on deck to execute ideas, it opens up a ton of creative possibilities.

It’s a release from the limitations of what any given office can handle. A lot of people in the publication world right now have big, progressive ideas but maybe not the full bandwidth to make them happen. We’re hoping that in that situation, they’ll consider collaborating with us.

You have to fight to have a space for radical ideas. Even if it is a wild failure.

How about funding for now?

Jake: We initially self-funded “Welcome to Dilley”, because we wanted to exert total control over what we were going to do. It was so much easier to do this when the expenses were split four ways. But we’re very grateful that the Economic Hardship Reporting Project retroactively provided support for some of our reporting costs.

Chris: It is an experiment. We’re confident that we can do this for clients, we can do this under grants, we can find interested fiscal sponsors and expand with more resources. While there are spaces within the industry that fosters experimental projects, there aren’t many.

Some publications are doing exciting things, Die New York Times has its virtual reality for instance, but it’s all in-house. If there were more opportunities that connected young, innovative artists with funding, both the next generation of image-makers and the industry would benefit from it. But with those still limited, you have to fight to have a space for radical ideas. Even if it is a wild failure.

Where do you look for distribution? What guides this process?

Chris: The core of our model is the fact that the content and the story dictate the form. A lot of freelancers in the industry don’t see potential in film festivals, in other exhibition spaces, and even in printed material. There are a lot of alternative markets that may not be mass distributed, but are equally as important.

Natalie: It’s a conversation that we want to have at the beginning of every project. What are we looking to tackle? Is it a book? Is it a freestanding website? Is it an interactive event? Is it traditional media partnership? Is it all of those things? Is it guerilla installation? That’s the first thing we ask in a Black Box project. We want to have ongoing conversations that push the boundaries of storytelling.

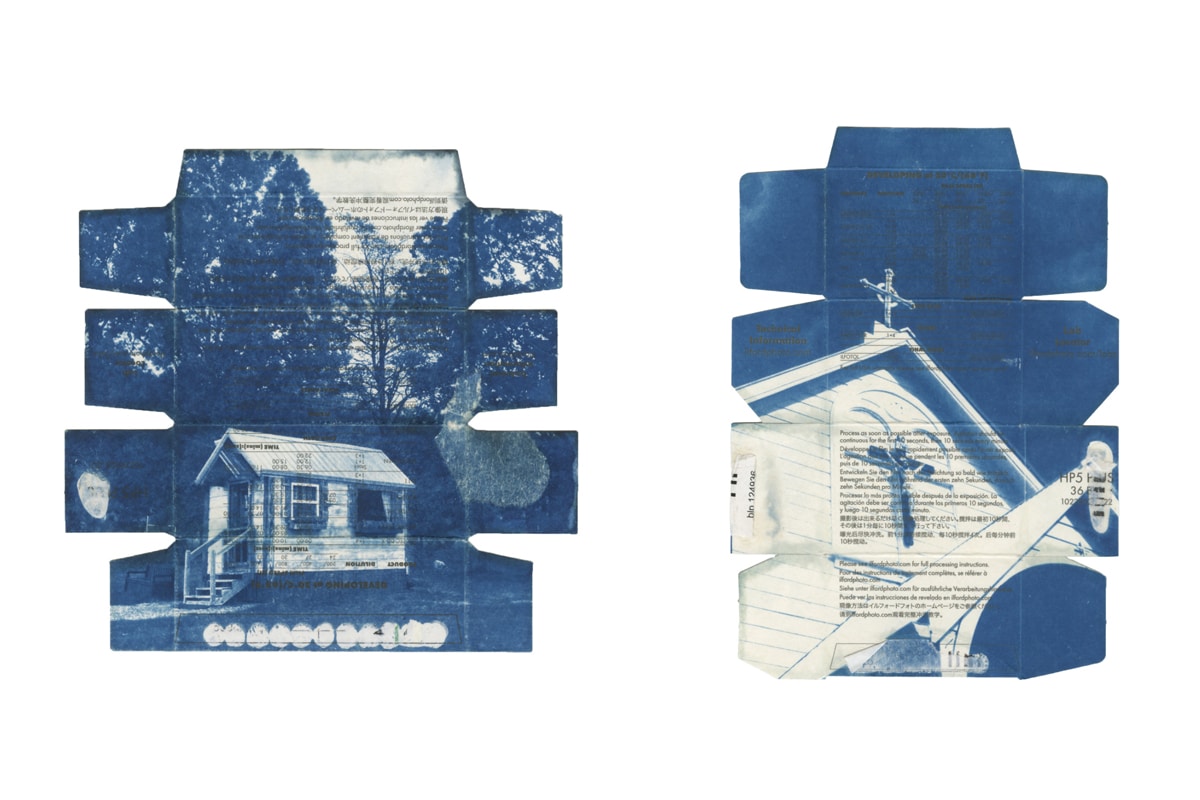

Black Box’s installation at Photoville 2015

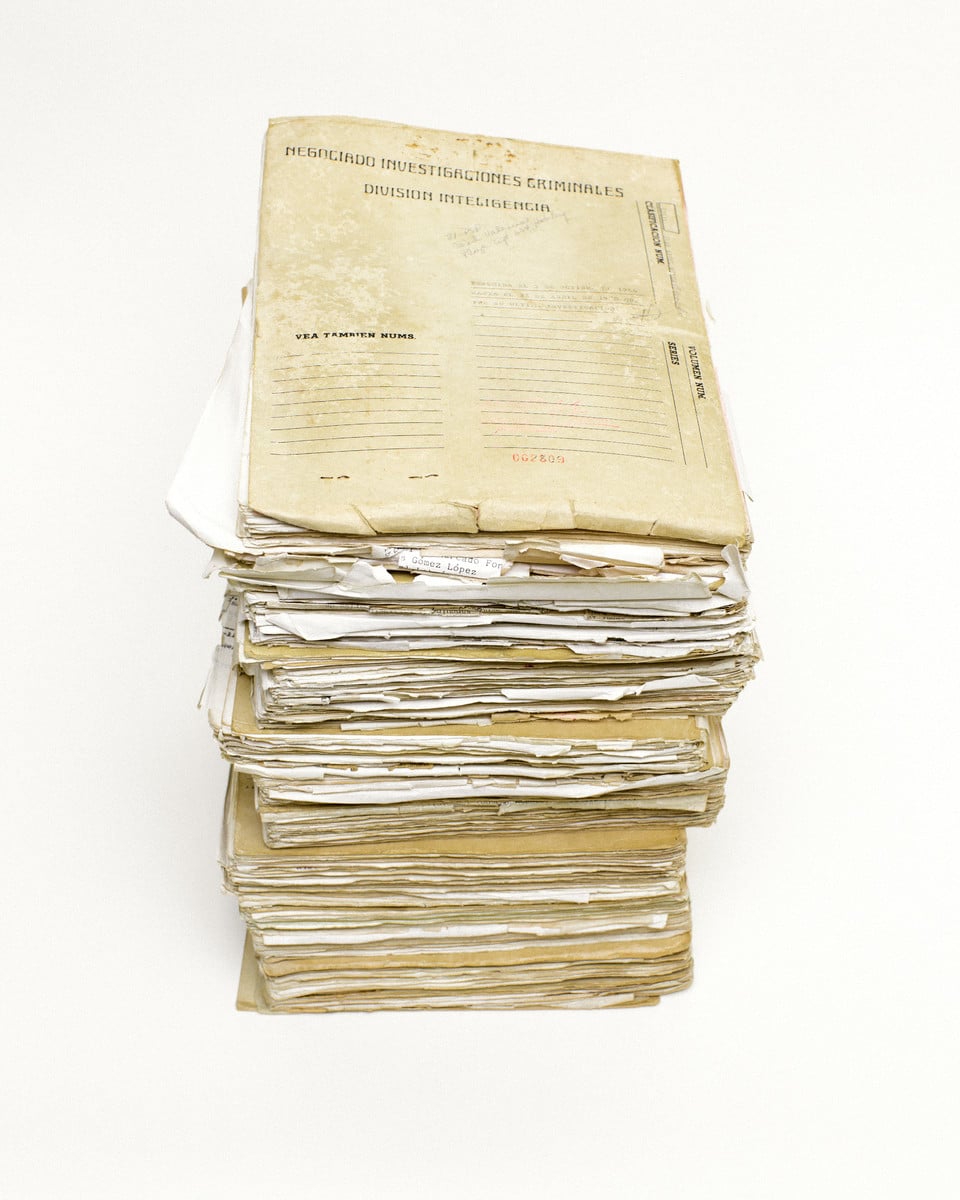

Black BoxDas Portfolio